Failed Battery Chemistry Offers a New Way to Destroy PFAS Forever Chemicals

Scientists have found an unexpected new weapon against PFAS, the stubborn “forever chemicals” that contaminate water, soil, and even our bodies: failed battery chemistry. What usually frustrates battery engineers—electrolytes degrading and components breaking down—has now been flipped into a powerful method for breaking some of the strongest chemical bonds known in nature.

This work comes from researchers in the lab of Assistant Professor Chibueze Amanchukwu at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering (UChicago PME), working closely with collaborators from Northwestern University. After three years of intentionally studying how batteries fail, the team has shown that those same destructive conditions can be used to degrade PFAS efficiently and almost completely.

The findings were published in Nature Chemistry and focus on a lithium-mediated electrochemical process that targets PFAS molecules directly, breaking them down into harmless components rather than leaving behind equally problematic fragments.

Turning battery failure into chemical success

Battery researchers typically try to avoid degradation at all costs. When electrolytes decompose or unwanted reactions occur, battery performance suffers. Amanchukwu’s group, however, took the opposite approach. They actively searched the scientific literature for examples of battery breakdown, especially cases where fluorinated compounds degrade under harsh electrochemical conditions.

The idea was simple but bold: if PFAS-like compounds already degrade inside batteries, why not harness that same chemistry intentionally?

Instead of seeing degradation as a problem, the team treated it as a clue. By recreating those failure conditions in a controlled way, they aimed to make PFAS molecules fall apart on purpose.

Why PFAS are so hard to destroy

PFAS, short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, are a massive family of chemicals used in products like firefighting foams, non-stick cookware, rain-resistant fabrics, food packaging, and many industrial applications. Their usefulness comes from one defining feature: extremely strong carbon–fluorine bonds.

Those bonds make PFAS resistant to heat, water, oil, and chemical attack. Unfortunately, they also make PFAS incredibly difficult to break down once released into the environment. As a result, PFAS persist for decades, earning them the nickname forever chemicals.

Many existing destruction methods rely on oxidation, which means stripping electrons away from molecules. That approach struggles with PFAS because fluorine holds onto electrons very tightly. Trying to oxidize PFAS often leads to incomplete breakdown or the formation of short-chain PFAS, which can be even harder to remove from water.

A reductive approach inspired by lithium batteries

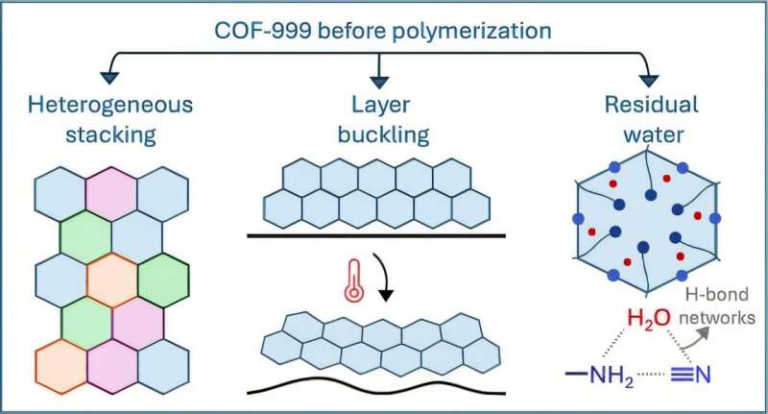

The UChicago–Northwestern team took a different route. Instead of oxidation, they focused on reduction, a process that adds electrons to molecules. Reduction can destabilize carbon–fluorine bonds—but only under the right conditions.

Water turned out to be a major obstacle. In aqueous systems, electrons tend to reduce water itself, producing hydrogen and oxygen instead of attacking PFAS. The breakthrough came when the researchers switched to non-aqueous battery electrolytes, similar to those used in lithium-metal batteries.

In this environment, PFAS molecules become the preferred target.

The researchers treated copper electrodes with lithium metal, a material well known in battery science for its high reactivity. When an electrical current was applied, lithium mediated a powerful electrochemical reaction that attacked the PFAS directly, snapping carbon–fluorine bonds apart.

Remarkable results with PFOA and beyond

The team focused first on perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), one of the most notorious and well-studied PFAS compounds. The results were striking.

The process achieved about 94% defluorination and 95% overall degradation, meaning nearly all carbon–fluorine bonds in PFOA were broken. Even more importantly, the PFAS did not just fragment into smaller molecules. Instead, the fluorine was largely converted into mineralized fluoride, a stable and manageable end product.

That matters because short-chain PFAS byproducts are often just as mobile and persistent as their longer counterparts. Avoiding their formation is a major challenge in PFAS remediation, and this method appears to solve that problem.

Encouraged by these results, the researchers expanded their testing. Out of 33 different PFAS compounds, 22 showed degradation levels above 70%, with some reaching up to 99% degradation.

Why electrochemistry makes this approach attractive

Electrochemical systems have several advantages over other PFAS destruction methods. Many competing techniques rely on high temperatures, high pressures, ultraviolet radiation, plasma systems, or specialized microbes. These approaches can be energy-intensive, complex, or difficult to scale.

Electrochemistry, by contrast, is modular and flexible. Small reactors can be built and powered by renewable electricity, including solar-charged batteries. This opens the door to localized treatment systems that handle PFAS waste streams on site, rather than transporting contaminated materials to large centralized facilities.

Another intriguing aspect is what happens to the fluorine after destruction. The mineralized fluoride produced in the reaction could potentially be reused to make PFAS-free fluorinated compounds, turning a pollutant into a useful raw material.

Expert reactions and scientific significance

Independent experts have described the work as a conceptual advance in PFAS treatment. Most prior electrochemical strategies focused on oxidation, while this study demonstrates the power of lithium-mediated electroreduction in a non-aqueous system.

The research also highlights the value of interdisciplinary thinking. Amanchukwu’s lab primarily focuses on battery electrolytes and energy storage, not environmental remediation. Yet the connection between battery failure and PFAS degradation turned out to be surprisingly direct.

The collaboration was supported through the Advanced Materials for Energy-Water Systems (AMEWS) Center, which aims to bring together researchers who might not normally work side by side. This project stands as a clear example of how cross-disciplinary science can uncover unexpected solutions to persistent problems.

Challenges before real-world deployment

Despite the impressive results, the technique is not ready for immediate use in water treatment plants. Because the process relies on non-aqueous electrolytes, PFAS would first need to be extracted and concentrated from contaminated water before treatment.

Lithium metal also reacts violently with water, raising engineering and safety questions for large-scale systems. Researchers will need to develop robust containment, recovery, and recycling strategies before the technology can move beyond the lab.

Still, the core chemistry is now proven. That opens the door to future refinements that could make the approach safer, cheaper, and more adaptable.

The bigger picture for PFAS research

PFAS contamination is a global issue, with growing regulatory pressure to remove these chemicals from drinking water and industrial waste streams. At the same time, many modern technologies still rely on fluorinated compounds, creating a difficult balance between performance and environmental responsibility.

This research shows that the same science used to build advanced energy systems can also help clean up their unintended consequences. By studying how materials fail, scientists may uncover new ways to fix problems that once seemed permanent.

In the fight against forever chemicals, battery failure—of all things—may turn out to be one of the most promising successes yet.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-02057-7