Fresh Produce May Soon Be Safer Thanks to a New Sanitizer Made From Upcycled Fermentation Waste

Texas A&M AgriLife Research has introduced a genuinely interesting development in food safety: a new way to sanitize fresh vegetables using waste liquid from probiotic fermentation. What’s normally thrown away during the production of foods like yogurt, kimchi, sauerkraut, and cheese is now proving surprisingly effective at reducing dangerous pathogens on produce. The method is simple, sustainable, and could be practical for real-world food processors who want a safer and more environmentally friendly alternative to chemical sanitizers.

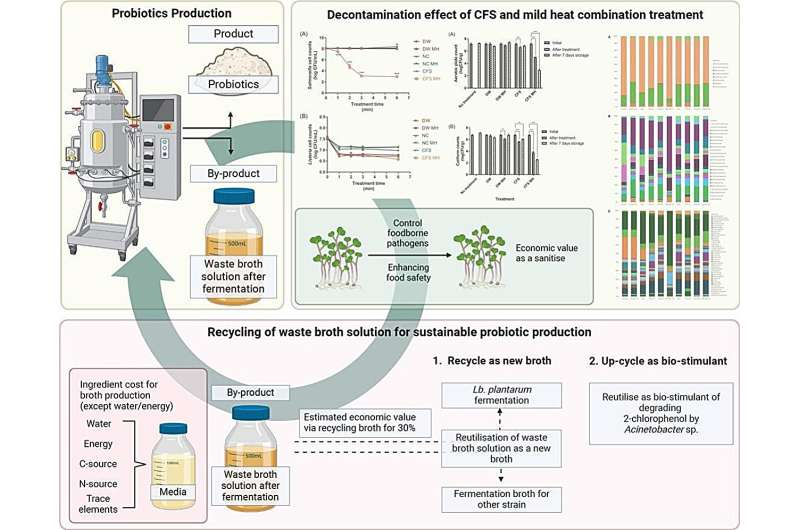

Researchers Seockmo Ku and Min Ji Jang from Texas A&M’s Department of Food Science and Technology discovered that culture waste broth—the leftover nutrient-rich liquid from culturing probiotics—still contains valuable organic compounds even after fermentation is complete. Instead of disposing of thousands of gallons of this broth, their idea was to make use of it by enhancing its natural antimicrobial properties. This led them to test a combination of the waste broth and gentle heating, which they later named CFS-MH, short for cell-free supernatant plus mild heat.

The process itself is straightforward. The team worked with broth left over from Lactiplantibacillus plantarum, a common probiotic species. They applied mild heat at roughly 113°F, which is significantly lower than typical sanitization temperatures. On its own, this gentle heating doesn’t sanitize produce. The broth alone also didn’t eliminate pathogens effectively. But combined, the two components produced an unexpectedly powerful antimicrobial response.

In controlled laboratory tests, this method cut Salmonella Typhimurium by more than five log colony-forming units, which is equivalent to a millionfold reduction. When tested on fresh radish sprouts, the treatment lowered both total bacteria and coliform counts by up to three log units, and these reductions remained stable for a full week under regular refrigerated storage. This consistency matters, because sprouts are one of the most sensitive fresh foods in terms of bacterial contamination. The fact that this method worked so effectively on a high-risk food is one of its strongest indicators of practical potential.

The researchers explain that the mild heat likely helps the broth’s organic acids penetrate and disrupt bacterial cells more easily. It’s a low-energy, low-chemical process that fits well with modern attempts to reduce reliance on harsher sanitizers like chlorine-based compounds. Since the broth is food-grade to begin with, there’s also a reduced chance of introducing unwanted residues or by-products into the produce.

Another angle the team explored was the environmental and economic feasibility of this solution. During probiotic production, a single 1,320-gallon fermentation can leave behind around 1,056 gallons of leftover broth. Traditionally, this has required proper disposal, transportation, and waste management—all of which cost money. By upcycling the broth into a functional sanitizer, a processor could generate about $100 of value per batch, which makes it comparable in cost to common sanitizers such as sodium hypochlorite. The additional benefit is waste reduction and a more circular production cycle, both of which appeal to companies aiming for sustainability targets.

This broader sustainability significance is part of why the study stands out. It shows how interdisciplinary thinking—mixing microbiology, food science, and engineering—can turn an overlooked by-product into something with tangible real-world value. Food processing industries are under increasing pressure to cut down on waste and reduce chemical use, and this approach hits both points at once.

Understanding the Science Behind Culture Waste Broth

To appreciate why this discovery works, it helps to understand what culture waste broth actually is. When probiotics like Lactiplantibacillus plantarum grow, they produce a wide range of compounds—primarily organic acids, but also peptides and other metabolites. In fermentation foods such as yogurt or kimchi, these compounds help shape flavor and natural preservation. However, after fermentation finishes, what remains is a liquid medium rich in these antimicrobial metabolites but no longer needed for production.

Traditionally, companies treat this spent medium as industrial waste even though it still contains bioactive compounds. Scientists have long known that organic acids from lactic acid bacteria can inhibit harmful pathogens, but they typically studied these effects during active fermentation or in controlled food systems—not as an upcycled sanitizer.

The Texas A&M approach expands this understanding by showing that even after fermentation is complete, the broth remains potent when combined with mild heat. Unlike chemical sanitizers, which can cause off-flavors, degrade textures, or raise consumer concerns, this method offers a natural, food-derived alternative.

Why Mild Heat Makes Such a Big Difference

At first glance, 113°F might seem too low to matter, since standard sanitization processes often require either high temperatures or strong chemicals. But this low heat level appears to alter the permeability of bacterial cell membranes, making pathogens significantly more vulnerable. The research team points out that heat doesn’t kill the bacteria by itself at this temperature. Instead, it enhances the ability of organic acids in the broth to enter the cells and disrupt essential functions.

This synergy—heat plus organic acids—explains why neither individual component achieved the same reduction in bacteria. The simplicity of the method makes it appealing for real-world application because processors wouldn’t need complex machinery or high energy inputs.

Potential Applications in the Produce Industry

Fresh produce has always been a challenge for food safety because washing alone doesn’t reliably remove pathogens. Sprouts, leafy greens, fresh herbs, and ready-to-eat vegetables are especially problematic since they are often eaten raw. Traditional sanitizers like chlorine are widely used but come with drawbacks, including the formation of possible by-products and varying effectiveness depending on organic load.

An upcycled, food-grade sanitizer that’s easy to implement and avoids harsh chemicals could fill a major gap in the industry. The fact that the researchers tested the method on radish sprouts—a product frequently associated with foodborne outbreaks—adds credibility to its potential usefulness. Consistent three-log reductions combined with week-long stability make this a promising candidate for commercial evaluation.

Broader Context: Upcycling and the Push for Sustainable Food Systems

Globally, food industries are moving toward minimizing waste and maximizing resource efficiency. Upcycling is becoming increasingly popular, from turning fruit peels into nutritional powders to repurposing spent grains from breweries. This fermentation broth sanitizer fits squarely into this trend. It reduces environmental impact while creating economic value, which is the core promise of circular food systems.

Furthermore, using waste streams from fermentation aligns with consumer interest in natural and clean-label solutions. It also reduces the volume of material requiring disposal, lowering transportation emissions and landfill usage.

What Comes Next

The method is still in its early stages and hasn’t been tested across a wide variety of produce. Questions remain about how it performs with leafy greens, fruits, root vegetables, and different storage conditions. There are also regulatory and scale-up steps needed before it could be approved for commercial use. Still, the findings suggest strong potential, and the concept of repurposing probiotic broth could inspire similar innovations across the industry.