Low-Cost Nickel–Molybdenum Catalyst Shows Strong Potential to Reduce Green Hydrogen Production Costs

A new study from researchers at SUNY Polytechnic Institute and the University at Albany has taken a close, detailed look at how a low-cost nickel–molybdenum catalyst behaves inside an anion exchange membrane (AEM) electrolyzer, a device that splits water into hydrogen and oxygen. The work focuses on understanding not just whether this catalyst performs well, but how it changes during operation and what those changes mean for long-term durability. Since green hydrogen remains limited by the high cost of electrolysis systems—especially because many rely on expensive precious-metal catalysts—this research offers a promising direction for lowering costs while enhancing scientific understanding of catalyst aging.

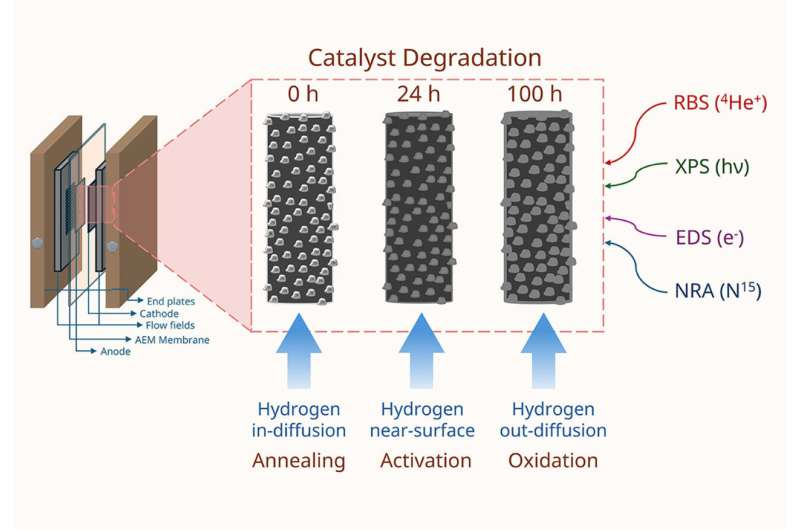

The study, titled Quantification of hydrogen and transition metals in ionomer-free MoNi4-MoO2 cathode catalyst layer for AEM electrolyzer, introduces a catalyst made from nickel and molybdenum, materials that are significantly cheaper and more abundant than precious metals like platinum or iridium. The team produced a MoNi4–MoO2 catalyst layer without using ionomers, then carefully examined how hydrogen and metal species distribute within the material during operation. By using advanced imaging and measurement tools, they were able to connect the catalyst’s surface and structural changes directly to its performance inside an AEM electrolyzer.

One of the key strengths of this work is that it does not stop at reporting whether the catalyst works—it digs into how it evolves under electrochemical conditions. The researchers observed that the nickel–molybdenum catalyst performs efficiently and can support active hydrogen production. However, they also found that the material slowly changes at its surface over time, altering its composition and potentially impacting its lifespan. Surface transformations, including oxidation and subtle structural shifts, appear to accumulate with continued operation. While these changes do not immediately cause performance failure, they do provide important insight into how long such a low-cost catalyst could realistically last in real-world systems.

To determine these effects, the team used techniques capable of tracking hydrogen content and transition-metal migration within the catalyst layer. Their methodology allowed them to identify where hydrogen accumulates, how metals redistribute, and which parts of the catalyst are more vulnerable to degradation. This level of detail is valuable because catalyst deterioration is one of the key technical challenges preventing low-cost electrolyzers from competing directly with more expensive systems.

The collaboration included Dr. Iulian Gherasoiu of SUNY Polytechnic Institute and Drs. Yamini Kumaran, Daniele Cherniak, Kyoung-Yeol Kim, and Haralabos Efstathiadis from the University at Albany. Together, they created a framework for tracking nanoscale catalyst behavior while relating those observations to the electrolyzer’s macroscopic performance. This dual-scale analysis helps researchers understand not just that the catalyst degrades, but why it happens and what mechanisms drive that degradation.

Their findings show three central outcomes:

- The nickel–molybdenum catalyst performs strongly and represents a feasible low-cost alternative for hydrogen production inside AEM electrolyzers.

- Surface changes accumulate over time, which means the catalyst gradually loses some of its original structure and composition.

- Their experimental method provides a powerful way to track catalyst aging and material transformations with precision, offering a valuable tool for designing longer-lasting catalyst materials in the future.

These results matter because AEM electrolyzers are considered a promising pathway for low-cost hydrogen production. Unlike proton exchange membrane (PEM) electrolyzers, which often rely on expensive rare metals, AEM systems can operate using more affordable materials—if those materials perform well enough and last long enough. The molybdenum-nickel combination in this study represents one of the more practical and scalable options researchers are currently developing.

Why Green Hydrogen Needs Cheaper Catalysts

Hydrogen produced from renewable electricity is one of the cleanest fuels available, but cost remains a major barrier. Traditional electrolyzers require components made from expensive metals, and their membranes or catalyst layers often degrade with use. This means companies face both high upfront costs and eventual replacement costs.

AEM electrolyzers could potentially change that calculus by allowing the use of earth-abundant metals like nickel, molybdenum, cobalt, or iron. Such systems also operate in alkaline conditions, which reduces corrosion problems and lowers engineering complexity compared to acidic PEM systems. The challenge, however, is that cheaper materials must match or approach the efficiency and durability associated with precious-metal catalysts. Understanding exactly how low-cost catalysts degrade is essential for solving this problem, and the new SUNY Poly/UAlbany study contributes directly to that goal.

What Makes the MoNi4–MoO2 Catalyst Noteworthy

The MoNi4 phase is known for its favorable hydrogen adsorption properties, meaning it can efficiently participate in the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). Meanwhile, MoO2 often helps stabilize the catalyst structure and promote better electron transport. When combined, these two materials offer a balanced blend of activity, stability, and affordability.

Past studies on MoNi4-based catalysts have shown excellent performance under laboratory conditions, sometimes approaching the activity levels of platinum-based catalysts. What has remained uncertain is how such materials hold up under prolonged operational stresses typical in industrial electrolyzers. This is where the new study adds value: it directly measures the hydrogen distribution and metal migration patterns that influence performance decay.

By identifying where degradation begins and how it progresses, researchers can now make informed adjustments to catalyst composition, support materials, manufacturing techniques, or protective coatings.

How This Research Helps the Future of Clean Hydrogen

This study provides a detailed roadmap for improving catalyst durability. With a clearer understanding of how nickel–molybdenum catalysts evolve inside an operational electrolyzer, scientists can now explore targeted enhancements such as:

- Surface engineering to reduce oxidation

- Doping with additional elements to improve metal stability

- Protective layers that minimize dissolution

- Optimized fabrication methods that produce more uniform catalyst films

These improvements can significantly increase the operating life of AEM electrolyzers, making them more attractive for widespread renewable-energy deployment. Better yet, because the materials are low-cost and easy to scale, they offer a realistic path toward affordable green hydrogen—a requirement for decarbonizing industries like steelmaking, ammonia production, long-duration energy storage, and heavy transport.

Reference to the Original Research Paper

Quantification of hydrogen and transition metals in ionomer-free MoNi4-MoO2 cathode catalyst layer for AEM electrolyzer

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2025.147829