New Catalyst Research Brings On-Demand Ozone Water Disinfection Closer to Reality

Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh, working alongside scientists from Drexel University and Brookhaven National Laboratory, have taken an important step toward transforming how water is disinfected in hospitals, treatment plants, and other critical facilities. Their new findings shed light on how to design catalysts that can safely and efficiently generate ozone directly in water, offering a promising alternative to traditional chlorine-based disinfection.

The study, published in the journal ACS Catalysis, focuses on solving a long-standing scientific puzzle: why some catalysts are capable of producing ozone through water electrolysis, yet fail quickly due to corrosion. By uncovering the microscopic processes behind both ozone formation and catalyst degradation, the team has provided a clear roadmap for building more durable, efficient, and safer disinfection technologies.

Why Chlorine-Based Disinfection Has Serious Drawbacks

Chlorine has been the backbone of water disinfection for decades. It is widely used to kill bacteria and pathogens in municipal drinking water systems, hospitals, and industrial settings. However, chlorine comes with major challenges that cannot be ignored.

First, chlorine is hazardous to store and transport, especially in large quantities. Accidental releases can pose serious health risks to workers and nearby communities. Second, chlorine reacts with organic matter in water to form disinfection byproducts, some of which are known or suspected to be carcinogenic. These concerns have long motivated scientists and engineers to search for safer alternatives that can provide the same level of microbial protection without the risks.

Ozone as a Cleaner and Safer Alternative

Ozone has emerged as a strong candidate to replace chlorine in many disinfection applications. It is an extremely powerful oxidant capable of destroying bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens quickly and effectively. One of ozone’s biggest advantages is that it naturally breaks down into oxygen, leaving behind no long-term chemical residues.

Despite these benefits, ozone has not been widely adopted for water disinfection on a large scale. The main reason is that ozone itself is unstable and cannot be easily stored or transported. Instead, it must be generated on demand, right where it is needed. This requirement has made ozone-based systems more complex and expensive than chlorine-based ones.

Using Water Electrolysis to Generate Ozone

One promising way to generate ozone on demand is through water electrolysis, a process that uses electric current to split water molecules. Under normal conditions, electrolysis produces oxygen and hydrogen. However, with the right catalyst, the process can be steered toward producing ozone instead of oxygen.

Only a small number of materials are known to enable this ozone-forming reaction. Among them, nickel- and antimony-doped tin oxide, often referred to as NATO catalysts, have stood out as relatively safe and cost-effective options. Unfortunately, these catalysts tend to degrade rapidly, making them unsuitable for long-term or large-scale use.

The Central Challenge: Catalysis Versus Corrosion

The research team set out to understand exactly why NATO catalysts break down so quickly. Led by John Keith, an R.K. Mellon Faculty Fellow in Energy at Pitt’s Swanson School of Engineering, and Maureen Tang, an associate professor at Drexel University, the group focused on the fundamental electrochemical mechanisms involved in multi-electron oxidation reactions.

Their work revealed a surprising and somewhat paradoxical insight. The very features on the catalyst surface that help generate ozone are also responsible for triggering corrosion. This dual role had not been clearly understood before and explains why progress in ozone-generating catalysts has been so slow.

What Happens at the Catalyst Surface

Using advanced quantum chemistry modeling, former Pitt doctoral student Lingyan Zhao investigated the atomic-level behavior of the catalyst surface. The simulations showed that defect sites—tiny irregularities in the crystal structure—play two critical roles.

On one hand, these defect sites accelerate ozone formation by enabling rapid electron transfer during electrolysis. On the other hand, they attract water molecules, which attach to the surface and form proton-rich networks of hydroxides and water. These networks are highly reactive and lead to corrosive reactions that gradually destroy the catalyst.

This finding explains why NATO catalysts can initially perform well but lose effectiveness over time. The process that makes them good at producing ozone also makes them vulnerable to chemical breakdown.

Experimental Proof and Validation

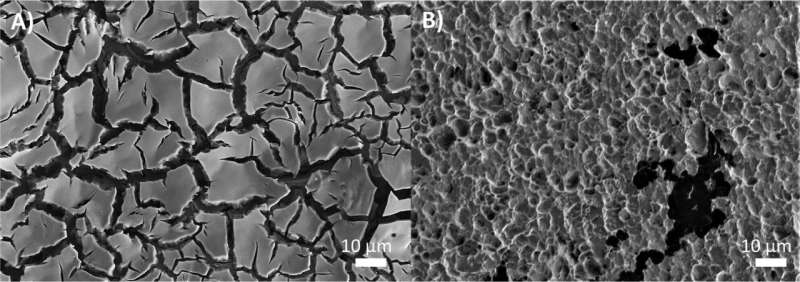

To confirm the computational results, Rayan Alaufey, the lead author of the study and a doctoral student at Drexel University, conducted a wide range of laboratory experiments. These experiments demonstrated how corrosion develops during extended electrolysis and how it directly interferes with ozone generation.

Advanced imaging techniques, including scanning electron microscopy, revealed visible changes on the catalyst surface after prolonged use. Blackened regions caused by carbon contamination appeared on electrodes after 24 hours of operation, offering physical evidence of the degradation process.

Together, the computational and experimental work provided a complete picture of how ozone generation and catalyst corrosion are tightly linked.

Designing the Next Generation of Ozone Catalysts

The most important outcome of this research is not just identifying the problem, but clearly defining the design principles needed to solve it. The team’s findings suggest that future catalysts must be engineered to separate ozone-generating activity from corrosion-prone sites.

In practical terms, this means designing materials that preserve the electronic properties required for ozone formation while preventing water from creating corrosive surface networks. Achieving this balance could lead to stable, long-lasting catalysts capable of producing ozone efficiently for extended periods.

Why This Matters for Water Treatment and Healthcare

If these design principles can be successfully applied, the impact could be significant. On-demand ozone generation would eliminate the need to store or transport hazardous disinfectants. Hospitals could disinfect water and surfaces more safely, while municipal water treatment facilities could reduce reliance on chlorine and its harmful byproducts.

Beyond water sanitation, the insights from this research could influence other areas of electrochemical engineering, including energy storage, hydrogen production, and advanced oxidation processes used in environmental cleanup.

Broader Scientific Significance

This study also highlights the importance of combining fundamental science with practical engineering. By understanding reactions at the atomic level, researchers can move beyond trial-and-error approaches and design materials with predictable, optimized performance.

The work underscores a broader lesson in catalysis research: activity alone is not enough. Stability and durability are equally critical, especially under extreme operating conditions like high-energy electrolysis.

Looking Ahead

While the study does not yet deliver a ready-to-use commercial catalyst, it provides the missing knowledge needed to build one. With clearer insight into how ozone formation and corrosion compete at the catalyst surface, researchers are now better equipped to develop the next generation of safe, sustainable, and efficient water disinfection technologies.

As global demand for clean water continues to grow, advances like this could play a crucial role in ensuring safer and more resilient sanitation systems for the future.

Research Paper:

https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.5c04461