New Technique Lights Up Where Drugs Go in the Body Cell by Cell

When we swallow a pill or receive an injection, it’s natural to assume scientists know exactly where that drug travels in the body and what it does along the way. In reality, for decades this has been one of the biggest blind spots in medicine. Researchers could measure how much of a drug ends up in an organ like the liver or kidneys, but identifying which exact cells a drug binds to — and where unexpected interactions might occur — has largely remained out of reach.

That may now be changing.

Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute have developed a powerful new imaging method that can reveal, cell by cell, where certain drugs bind throughout the entire body. The technique, called vCATCH, offers an unprecedented look at how drugs behave once they enter living organisms, potentially transforming how medicines are developed, tested, and evaluated for safety.

Why tracking drugs inside the body has been so difficult

Traditional drug-tracking techniques come with major limitations. Researchers can grind up tissues and analyze drug concentrations, but this destroys spatial information. Imaging approaches like radioactive tracers can show where drugs accumulate, but only at a low resolution, usually at the level of whole organs rather than individual cells.

As a result, scientists have often relied on educated guesses. A drug designed for a particular target is assumed to mainly act there, with side effects treated as unfortunate but mysterious consequences. According to Li Ye, professor at Scripps Research and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator, the detailed cellular journey of drugs inside the body has long been a black box.

Introducing vCATCH and what makes it different

The new method builds on earlier work from Ye’s lab. In 2022, the team introduced CATCH, a technique that allowed researchers to visualize drug binding on the surface of organs, such as the brain. However, that method couldn’t reach deep tissues.

With vCATCH, short for volumetric Clearing-Assisted Tissue Click Chemistry, the approach has now been scaled up to work throughout the entire body, including deep regions of the brain, heart, lungs, liver, spleen, and blood vessels.

The key breakthrough is that vCATCH doesn’t just show where a drug travels — it shows where it actually binds, at single-cell resolution.

How the vCATCH technique works

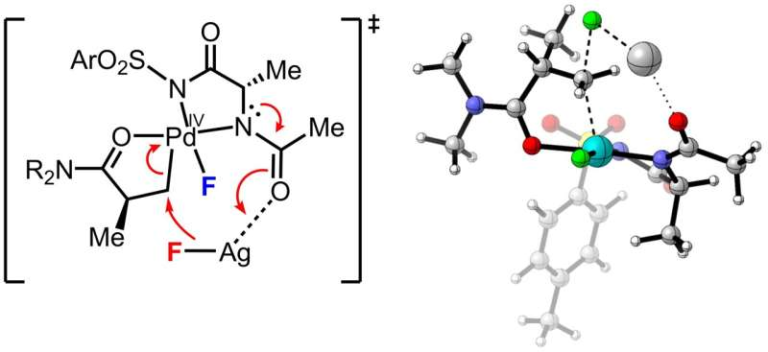

vCATCH is designed specifically for covalent drugs, a class of medications that form permanent chemical bonds with their targets. These drugs are increasingly common, especially in cancer therapy.

Here’s how the process works in detail:

- Researchers attach a tiny chemical handle to a covalent drug without changing how it behaves.

- The modified drug is injected into mice, where it binds to its usual cellular targets.

- After the tissues are collected, scientists trigger a highly selective chemical reaction that attaches a fluorescent tag to the drug’s chemical handle.

- This reaction relies on click chemistry, a precise and efficient chemical process that snaps molecules together like LEGO bricks.

Click chemistry was developed at Scripps Research by K. Barry Sharpless, who received the 2022 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this innovation.

Overcoming a major technical obstacle

Scaling CATCH to work throughout whole organs wasn’t easy. One major problem was copper, which is essential for the click chemistry reaction. Proteins inside tissues tend to absorb copper, preventing it from penetrating deep into organs. Early attempts only lit up drug binding on tissue surfaces.

The solution was clever and counterintuitive. The researchers pre-treated tissues with excess copper to block unwanted binding sites. They then repeated the tagging process up to eight cycles, bathing tissues multiple times in copper and fluorescent tags.

Normally, repeated chemical treatments would cause background noise and false signals. But vCATCH avoids this issue because click chemistry is extremely selective, ensuring that only drug-bound sites light up.

Mapping drugs across the entire body

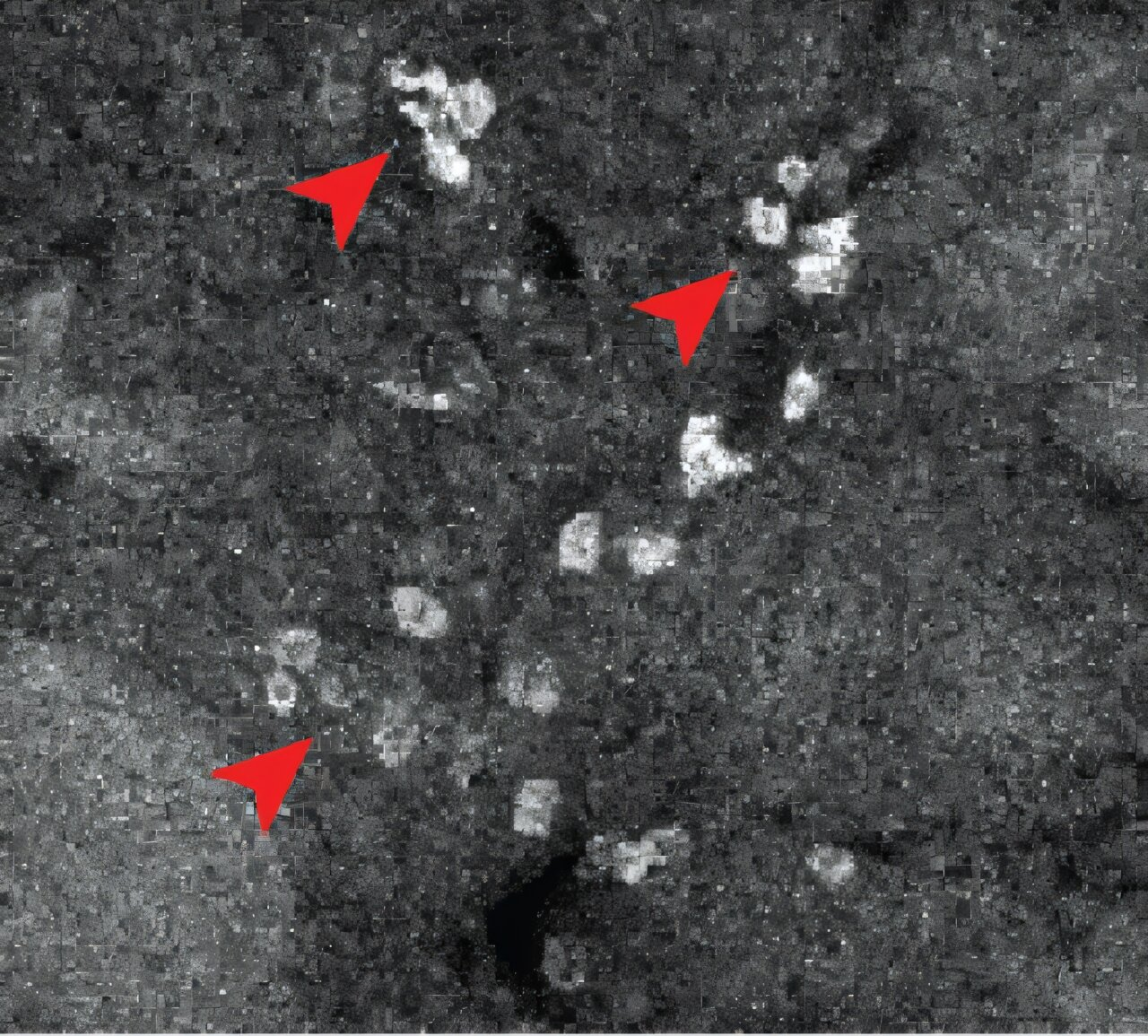

Using vCATCH, the team created whole-body cellular maps for two widely prescribed cancer drugs:

Ibrutinib (Imbruvica), used to treat blood cancers

Afatinib (Gilotrif), prescribed for non-small cell lung cancer

The results were both reassuring and surprising.

Afatinib behaved largely as expected, spreading widely throughout lung tissue, consistent with its intended use. Ibrutinib, however, revealed a far more complex pattern.

Unexpected findings with ibrutinib

Ibrutinib is known to cause side effects such as irregular heartbeat and bleeding problems, but the precise biological reasons have been unclear. vCATCH showed that the drug binds not only to its intended targets in blood cells, but also to:

- Immune cells in the liver

- Heart tissue

- Cells lining blood vessels

These unexpected binding sites offer a plausible explanation for its cardiovascular risks. Instead of acting only where doctors expect, the drug interacts with cell types that influence heart rhythm and blood clotting.

Importantly, this doesn’t mean the drug is unsafe — it has saved many lives — but it shows how deeper insight into drug behavior could help design safer versions in the future.

The role of AI in analyzing the data

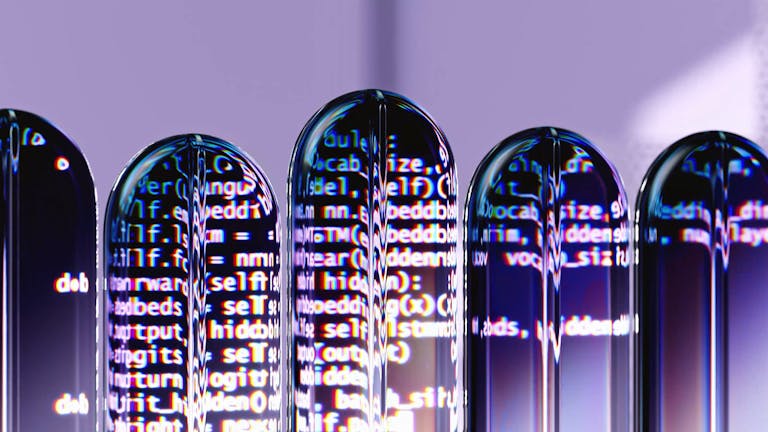

Each vCATCH experiment produces multiple terabytes of imaging data per mouse. To handle this massive volume of information, the researchers collaborated with engineers to build AI-based analysis pipelines.

These tools automatically identify and classify drug-bound cells across different organs, allowing researchers to study patterns that would be impossible to detect manually.

Why this matters for drug development

vCATCH has the potential to reshape how drugs are tested before they ever reach human trials. Instead of waiting for side effects to appear in patients, scientists could:

- Detect off-target binding early in development

- Compare how strongly drugs bind to diseased vs healthy tissues

- Reduce the risk of unexpected toxicity

- Design drugs that are more precise and selective

This could be especially valuable for late-stage drug candidates, where failure due to safety issues is extremely costly.

Beyond cancer drugs

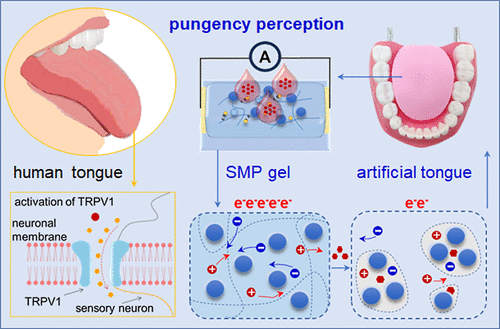

While the current study focused on cancer therapies, the applications go much further. Ye’s team is now exploring how vCATCH can be used to study:

- Whether cancer drugs truly prefer tumor cells over normal cells

- How antidepressants and antipsychotics bind to different cell types in the brain

- The cellular targets of drugs involved in neurological and immune disorders

Because covalent drugs are used across many medical fields, the reach of this technique is broad.

A new era of cellular-level pharmacology

For decades, drug development has relied on partial information. vCATCH offers a way to finally see the full cellular footprint of a drug inside the body. Instead of guessing, researchers can now directly observe where drugs bind, where they don’t, and where unexpected interactions might explain side effects.

This kind of insight doesn’t just improve safety — it deepens our understanding of how medicines actually work inside living systems.

Research paper reference

Mapping cellular targets of covalent cancer drugs in the entire mammalian body

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2025.11.030