Oil-in-Water Droplets Are Showing Cell-Like Behavior by Growing Arm-Like Extensions

Scientists are used to drawing a sharp line between living cells and non-living matter. Living cells sense their surroundings, move toward nutrients, and respond intelligently to chemical signals. Non-living materials, on the other hand, are usually passive. A new study from researchers at Penn State University challenges this distinction by showing that simple oil-in-water droplets can behave in surprisingly life-like ways. Under the right conditions, these droplets grow thin, arm-like extensions that closely resemble filopodia, the protrusions living cells use to explore and interact with their environment.

The research reveals not only how these arms form, but also how they grow directionally, responding to specific chemical cues in their surroundings. The work adds an important piece to the puzzle of how non-living matter on early Earth may have gradually transitioned into life.

Droplets That Behave Like Cells

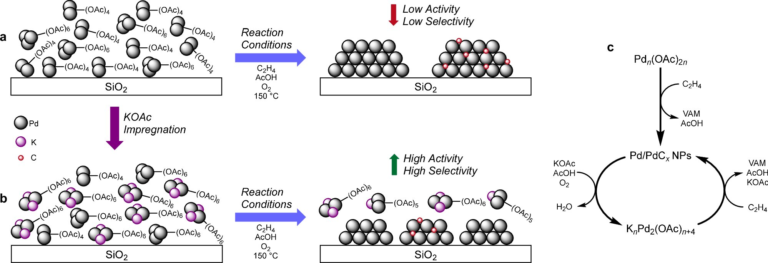

The study focuses on droplets made of oil suspended in water containing a surfactant, a soap-like chemical that reduces surface tension. Surfactants are common in everyday life, found in detergents and cleaning products, but they also play a crucial role in chemistry and biology by organizing molecules at interfaces.

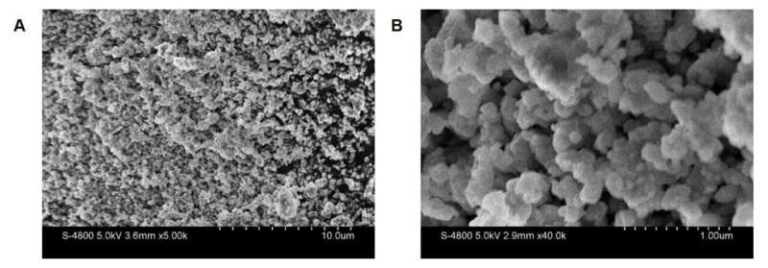

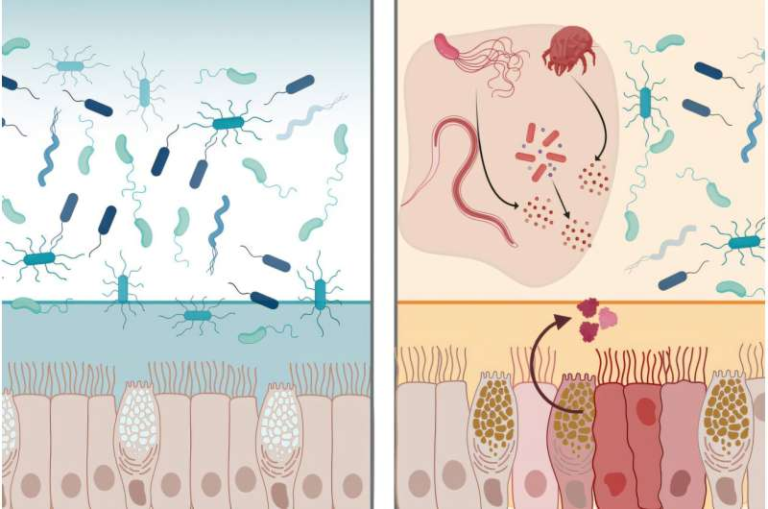

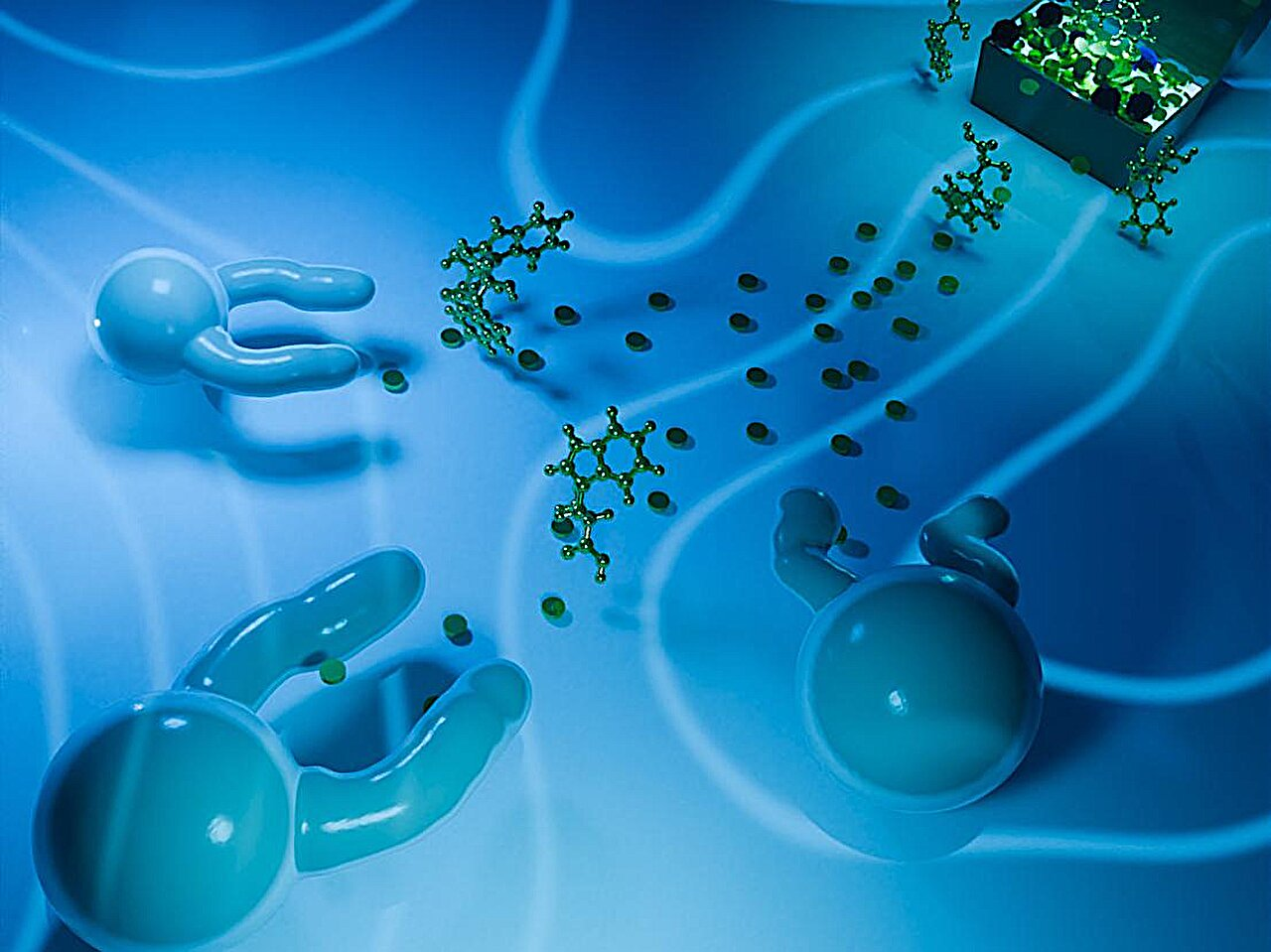

When certain oils are placed in this surfactant-rich water, something unexpected happens. Instead of remaining smooth and spherical, the droplets begin to sprout narrow, finger-like extensions. These extensions strongly resemble filopodia, which are thin protrusions that many living cells use for sensing, movement, and navigation.

What makes this behavior remarkable is that the droplets are not alive. They contain no DNA, no proteins, and no metabolic machinery. Yet they display behaviors that look strikingly similar to those seen in unicellular organisms.

How the Arm-Like Structures Form

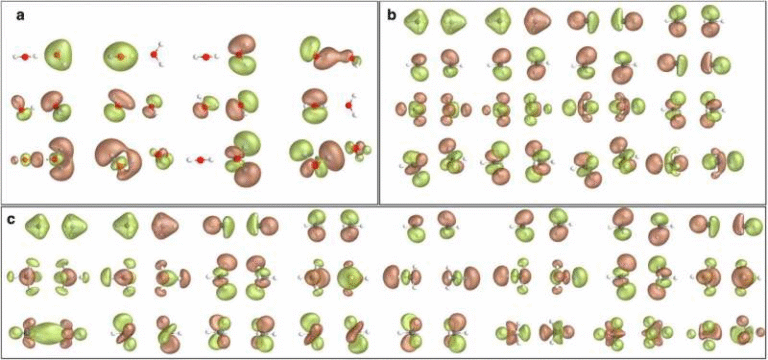

The formation of these filopodia-like arms begins with solubilization, a process in which small amounts of oil dissolve into the surrounding water with the help of surfactant molecules. As the oil slowly dissolves, surfactant molecules penetrate and accumulate at the surface of the droplet.

This accumulation creates mechanically unstable layers on the droplet’s surface. Instead of staying evenly distributed, these layers destabilize the interface between oil and water. The instability causes the surface to buckle and stretch outward, forming thin extensions that protrude from the droplet.

In simple terms, the arms are not pushed out by motors or biological machinery. They emerge naturally from chemical and physical forces acting at the droplet’s surface.

Directional Growth Guided by Chemical Gradients

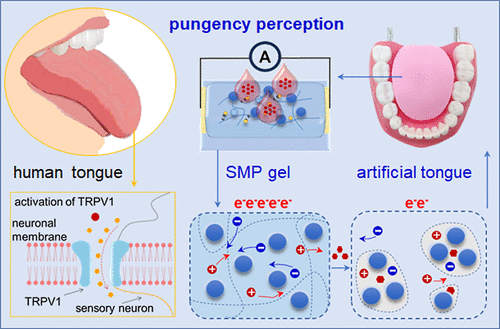

One of the most important findings of the study is that these filopodia-like arms do not grow randomly. Instead, they grow directionally, guided by chemical gradients in the surrounding environment.

When the concentration of surfactant is higher on one side of a droplet, the arms preferentially grow toward that higher concentration. This mirrors how living cells extend filopodia toward nutrients or signaling molecules.

The droplets also respond to amino acids, which are the building blocks of proteins. Depending on the chemical properties of the amino acid, the arms may grow toward regions of higher concentration or away from them. This type of behavior is well known in biology, where microorganisms move toward attractive chemicals and avoid harmful ones.

Seeing this same pattern emerge in a non-living system suggests that directional sensing does not require life, only the right chemical conditions.

Why Scientists Are Studying These Droplets

The researchers are not suggesting that these droplets are alive. Instead, they are using them as cell models to better understand how life-like behaviors could arise from simple chemistry.

One of the biggest unanswered questions in science is how life first emerged on Earth roughly three to four billion years ago. Early Earth had no cells, no enzymes, and no genetic systems as we know them today. Yet at some point, simple molecules organized themselves into systems capable of sensing, responding, and eventually reproducing.

By studying oil droplets that can mimic cellular behaviors, scientists can explore intermediate stages between non-living chemistry and fully developed life.

Insights Into the Matter-to-Life Transition

Living cells are incredibly complex, which makes it difficult to imagine how they evolved from simple molecules. Research like this breaks the problem into smaller, more manageable steps.

The droplets show that:

- Environmental sensing can emerge without biology

- Directional responses can arise purely from chemical gradients

- Complex behaviors do not necessarily require complex components

These findings support the idea that early life may have begun with relatively simple, self-organizing chemical systems that gradually became more sophisticated over time.

Recognition and Scientific Impact

The study was published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society, one of the most respected journals in chemistry. It is scheduled to appear on the front cover of an upcoming issue, highlighting its importance to the field.

In addition, the American Chemical Society selected the work for its Research Headlines video series, which showcases particularly interesting and impactful studies.

The first author of the paper, Sanjana Krishna Mani, is a graduate student in chemistry at Penn State’s Eberly College of Science. She also received the Best Poster Award for presenting this research at the 2025 Materials Day, hosted by the Penn State Materials Research Institute in October.

Beyond Origins of Life: Practical Applications

While the study is deeply connected to questions about the origin of life, its implications extend beyond fundamental science.

Understanding how simple materials respond to chemical cues could help researchers design lifelike materials that adapt to their surroundings. Such materials could be useful in:

- Soft robotics, where flexible structures respond to environmental changes

- Chemical sensing systems that detect and react to specific molecules

- Smart materials that change shape or function when exposed to certain chemicals

By learning from these droplet systems, scientists can explore new ways to build responsive, adaptive technologies without relying on living cells.

Why Filopodia Matter in Biology

In living organisms, filopodia play a critical role in many processes. Cells use them to explore their environment, attach to surfaces, communicate with neighboring cells, and migrate during development or healing.

Seeing similar structures emerge in oil droplets suggests that filopodia-like behavior may be rooted in basic physical principles, not just biological complexity. This insight helps bridge the gap between physics, chemistry, and biology.

A Small System With Big Implications

At first glance, oil droplets forming tiny arms in water might seem like a niche laboratory curiosity. But this work demonstrates how simple chemical systems can display surprisingly rich behavior. It reminds us that the boundary between living and non-living matter is not always as clear as it seems.

By carefully dissecting how these arms form and respond to chemical signals, the researchers have provided a clearer view of how life-like behavior can emerge from non-living materials. It is a small but meaningful step toward understanding one of science’s biggest mysteries.

Research Paper:

https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5c11719