Scientists Develop a One-Step Method to Precisely Add Fluorine to Drug Molecules

Chemists at Scripps Research have unveiled a long-awaited breakthrough in medicinal chemistry: a single-step method that allows fluorine atoms to be added precisely and stereoselectively to complex, drug-like molecules. This advance tackles one of the most persistent challenges in chemical synthesis and opens new possibilities for drug development and medical imaging, particularly PET scans.

Fluorine plays an outsized role in modern medicine. Despite being a relatively rare element in nature, it appears in a striking number of pharmaceuticals. In some years, nearly half of all FDA-approved drugs contained at least one fluorine atom. The reason is simple: fluorine can dramatically improve how drugs behave in the body, often making them more potent, more stable, and longer-lasting. Yet adding fluorine to molecules in a controlled and predictable way has historically been difficult, especially when working with the sturdy carbon–hydrogen (C–H) bonds found in most drug-like compounds.

The new method developed at Scripps Research changes that landscape.

Why Fluorine Is So Important in Medicine

Fluorine’s value in pharmaceuticals comes from its unique chemical properties. It is highly electronegative, meaning it can subtly alter how electrons are distributed within a molecule. This can improve how tightly a drug binds to its target, reduce unwanted side reactions in the body, or slow down how quickly the drug is broken down by metabolism.

Beyond traditional drugs, fluorine is also critical in medical imaging. The radioactive isotope fluorine-18 is the workhorse of positron emission tomography (PET), a powerful technique that allows doctors and researchers to track biological processes inside the body in real time. PET scans are widely used in oncology, neurology, and cardiology.

Despite fluorine’s importance, directly installing it into molecules—especially at later stages of synthesis—has been one of the most stubborn problems in chemistry.

The Challenge of Stereoselective C–H Fluorination

Carbon–hydrogen bonds are everywhere in organic molecules, but they are also remarkably unreactive. Replacing one hydrogen atom with fluorine might sound simple, but doing so at the right position and from the right direction in three-dimensional space is extremely difficult.

This directional control, known as stereoselectivity, is crucial in drug design. Many molecules exist in mirror-image forms, called stereoisomers, and often only one of those forms has the desired biological effect. The wrong stereoisomer can be inactive or even harmful.

Previous approaches to stereoselective C–H fluorination relied on expensive specialty reagents, multi-step reaction sequences, or methods that were incompatible with complex drug molecules. These limitations made it impractical to use fluorination as a late-stage modification in real-world pharmaceutical development.

A New One-Step Solution from Scripps Research

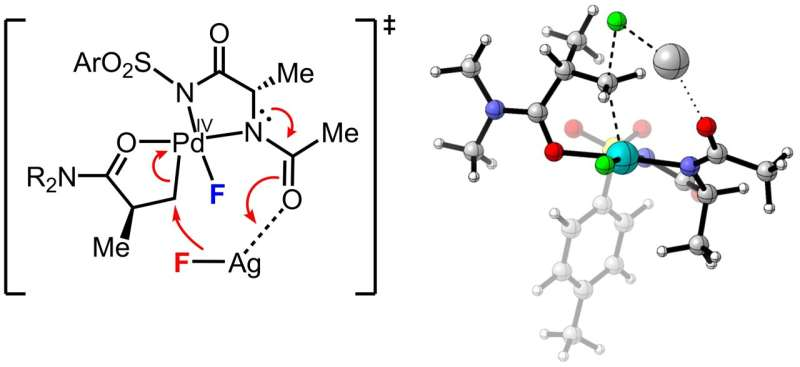

The Scripps Research team, led by chemist Jin-Quan Yu, has now developed a method that overcomes these barriers. Their approach allows chemists to stereoselectively attach fluorine atoms directly to C(sp³)–H bonds in a single step, even in complex, drug-like molecules.

At the heart of the method is a palladium-based catalyst paired with a carefully designed chiral ligand. This ligand acts like a molecular guide, steering the catalyst to a specific location on the target molecule and positioning it precisely in three-dimensional space. The result is the formation of only the desired fluorinated stereoisomer, with high efficiency and selectivity.

What makes this especially notable is that the reaction uses simple, inexpensive fluoride salts, such as potassium fluoride. Fluoride is not only cheap and widely available, but it is also the same chemical form used to produce fluorine-18 for PET imaging.

Tested on Real Drug-Like Molecules

The researchers didn’t limit their work to simple model compounds. They demonstrated the method on a wide range of medicinally relevant molecules, including derivatives of flutamide, a drug used to treat prostate cancer, and fentanyl, a powerful opioid used for pain relief.

In these cases, the reaction delivered high yields and excellent enantioselectivity, meaning the process consistently produced the correct three-dimensional form of the molecule. This level of precision is exactly what medicinal chemists need when fine-tuning drug candidates.

A Major Boost for PET Imaging and Radiochemistry

One of the most exciting aspects of this discovery is its impact on PET tracer development. Fluorine-18 has a relatively short half-life of about 110 minutes, which means chemists must work quickly to incorporate it into molecules before it decays.

The new fluorination reaction can be completed in around 45 minutes, making it fast enough to fit comfortably within the tight timelines required for clinical PET imaging. Older methods were often too slow or required multiple steps, severely limiting the types of molecules that could be labeled with fluorine-18.

With this new approach, fluorine-18 can be taken directly from a cyclotron—the machine that produces the radioactive isotope—and installed into drug-like molecules in a single step. This greatly simplifies the process and expands the range of PET tracers that can realistically be made.

In collaboration with Bristol Myers Squibb, the team demonstrated that their method could successfully radiolabel biologically active compounds, showing clear potential for industrial and clinical applications.

Late-Stage Functionalization and Why It Matters

A key advantage of this chemistry is its suitability for late-stage functionalization. This means fluorine—or fluorine-18—can be added at the final step of synthesis, without having to redesign and rebuild the entire molecule from scratch.

For drug discovery, this is a big deal. Late-stage modification allows researchers to quickly explore how small changes affect a drug’s performance, speeding up optimization and reducing costs. For imaging, it enables rapid attachment of radioactive tracers to existing drug molecules, making it easier to study how those drugs behave in the body.

Beyond Fluorine: A Broader Platform

Interestingly, the researchers have already shown that the same design principles behind this fluorination method can be extended to other elements. Variations of the platform have been applied to incorporate oxygen, nitrogen, and other halogens, giving chemists a versatile toolkit for modifying molecules with high precision.

This suggests the work is not just a solution to a single problem, but part of a broader strategy for reimagining how catalysts are designed for challenging chemical transformations.

Why This Discovery Matters

This new method solves a problem that chemists have been wrestling with for decades. It combines precision, speed, affordability, and real-world applicability in a way that previous approaches could not. By making stereoselective C–H fluorination practical, it opens the door to faster drug development, more accessible PET imaging agents, and new ways to study and treat disease.

In short, it changes how chemists think about adding fluorine to molecules—and that shift could ripple across pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, and beyond.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41929-025-01366-x