Scientists Identify a Promising New Drug Target That Could Work Against a Huge Class of Viruses

Researchers from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC) have uncovered a critical weakness shared by a large group of viruses, a finding that could significantly reshape how antiviral drugs are designed in the future. The study, published in Nature Communications, explains in precise molecular detail how enteroviruses—a family of viruses responsible for diseases such as polio, myocarditis, encephalitis, and the common cold—begin replicating inside human cells.

What makes this discovery especially important is that the newly identified target is highly conserved across many different enteroviruses, raising the possibility of a single antiviral strategy that could work against many infections rather than just one.

Understanding the Enterovirus Challenge

Enteroviruses are small but remarkably efficient pathogens. Their genetic material consists of a single strand of RNA, which must perform two major tasks inside a host cell: it must act as a template to produce viral proteins, and it must be copied to generate new viral genomes. Unlike human cells, which have complex machinery to handle these tasks, enteroviruses rely on a compact set of viral proteins to hijack the host’s cellular systems.

One of the central players in this process is a viral fusion protein known as 3CD. This protein combines two critical functions: one part, called 3C, cuts long viral protein chains into usable pieces, while the other part, 3D, acts as an RNA polymerase, an enzyme that copies the viral RNA. Human cells do not have a similar polymerase, so the virus must bring its own.

While scientists have known about these proteins for years, exactly how they interact with viral RNA to kick off replication has remained unclear—until now.

The RNA Cloverleaf That Starts It All

At the heart of the discovery is a distinctive RNA structure located at the beginning of the enterovirus genome. This structure, often described as a cloverleaf, acts as a molecular docking platform. Earlier work had identified the cloverleaf itself, and other studies had resolved the structures of individual viral proteins. What was missing was a clear picture of how the RNA and proteins come together during the earliest steps of viral replication.

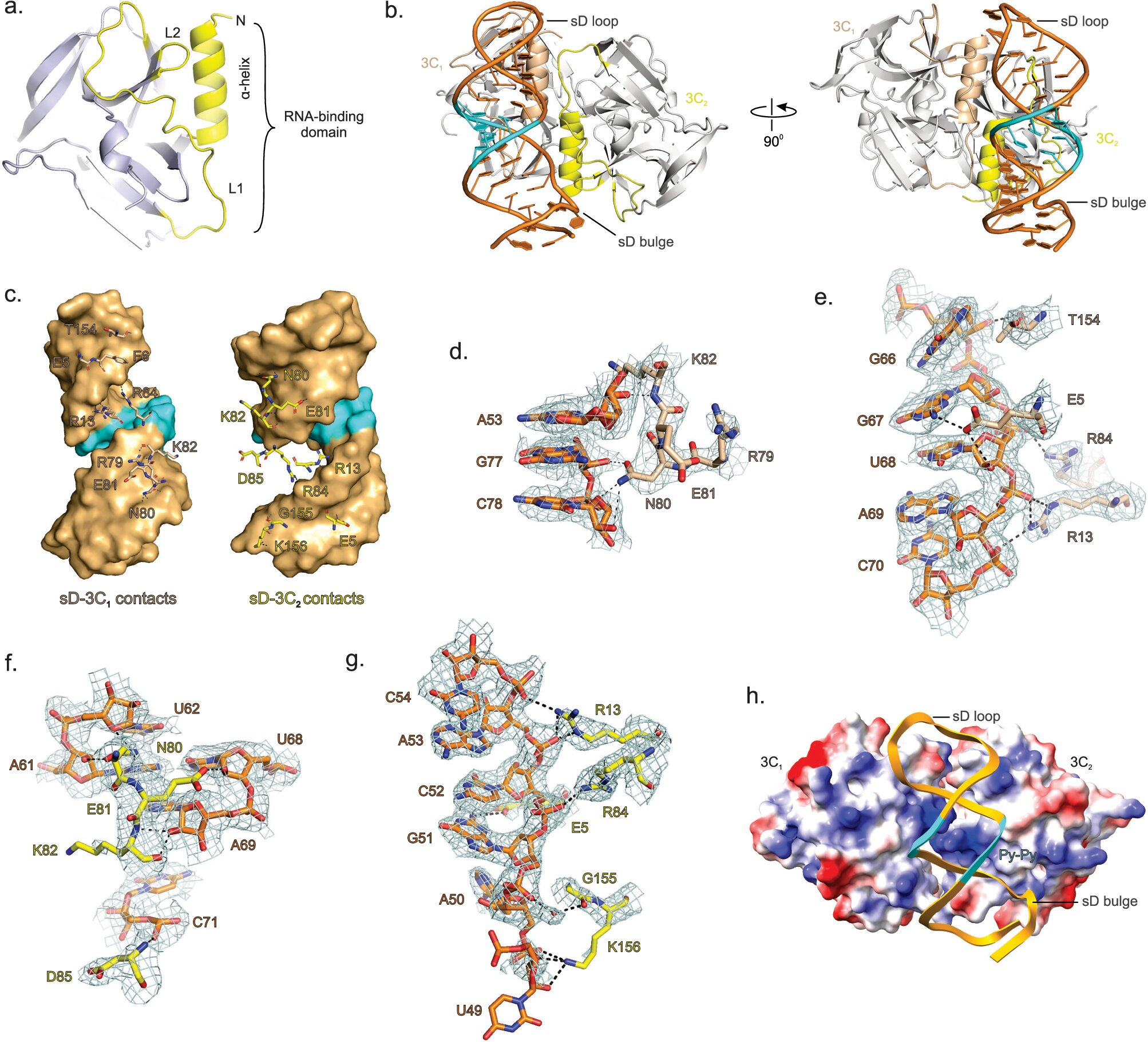

The UMBC research team, led by associate professor Deepak Koirala and recent Ph.D. graduate Naba Krishna Das, successfully captured this interaction in high resolution. They demonstrated that the 3C domain of the 3CD protein binds directly to a specific subdomain of the RNA cloverleaf, known as the sD subdomain. This binding event sets off a cascade of interactions that ultimately assemble the viral replication complex.

Once attached, the viral protein recruits additional components, including the host protein PCBP2, which helps stabilize the complex. This assembly marks the moment when the virus commits to copying its genome.

A Molecular Switch for Viral Replication

One of the most interesting insights from the study is that this RNA-protein complex also functions as a regulatory switch. When the 3CD protein is bound to the cloverleaf RNA, the virus prioritizes RNA replication. When the protein detaches, the same RNA can instead be used to produce viral proteins.

This dual functionality allows the virus to carefully balance its needs inside the host cell, ensuring efficient reproduction without wasting resources. Understanding this switch is critical, because disrupting it could prevent the virus from multiplying at all.

Settling a Longstanding Scientific Debate

The researchers also addressed a point of disagreement within the scientific community. Previous studies had proposed different models for how many 3CD molecules bind to the RNA cloverleaf. Using X-ray crystallography, along with isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and biolayer interferometry (BLI), the UMBC team demonstrated that two complete 3CD molecules bind side by side on the RNA structure.

This finding rules out earlier suggestions that the proteins form a single fused complex. Each bound molecule brings its own RNA polymerase domain, meaning two polymerases are recruited during replication initiation. Why exactly two are required is still unknown, but the structural evidence now provides a clear and definitive picture of how the interaction occurs.

Why This Discovery Matters for Drug Development

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of the study is how conserved this mechanism appears to be. The researchers examined seven different types of enteroviruses, and all of them used nearly identical RNA structures and binding strategies. This level of conservation suggests that the cloverleaf RNA and its interaction with 3CD are essential for viral survival.

From a drug development perspective, this is extremely good news. Viral proteins often mutate quickly, allowing viruses to escape drugs designed to target them. However, RNA structures that are essential for replication tend to be far more stable, because even small changes can render the virus nonfunctional.

This means the RNA cloverleaf and the RNA–protein interface represent a particularly attractive drug target—one that is less likely to evolve resistance.

A New Direction for Antiviral Strategies

Current antiviral research has already explored drugs that inhibit the enzymatic activities of 3C and 3D. The new findings add another layer of opportunity. Instead of targeting enzyme activity alone, future drugs could be designed to block the physical interaction between the viral RNA and its proteins.

With the newly resolved high-resolution structures, scientists can now pursue structure-based drug design, creating molecules that fit precisely into the binding interface and prevent the replication complex from forming. Such drugs could potentially act as broad-spectrum antivirals, effective against many enteroviruses at once.

A Broader Look at Enteroviruses and Human Health

Enteroviruses are among the most common human pathogens worldwide. While many infections cause mild symptoms or go unnoticed, others can lead to severe neurological and cardiac conditions, especially in children and immunocompromised individuals. Vaccines exist for only a few enteroviruses, most notably polio, leaving a large gap in prevention and treatment options.

A drug that targets a shared replication mechanism could help address this gap, offering protection against diseases that currently lack specific therapies. It could also be rapidly deployed in outbreak situations involving newly emerging enteroviruses.

Why Basic Science Still Matters

This study is a strong reminder of the value of fundamental molecular research. By carefully dissecting how viruses operate at the atomic level, scientists can reveal vulnerabilities that are invisible at larger scales. Even though the enterovirus genome is roughly the size of a single human messenger RNA, it encodes a remarkably efficient system for survival and replication.

Understanding that system in detail is what makes it possible to stop it.

Research paper:

Structural basis for 3C and 3CD recruitment by enteroviral genomes during negative-strand RNA synthesis – Nature Communications (2025)

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-64376-0