10 Years Since the Aliso Canyon Disaster: What We’ve Learned and What Still Remains Unresolved

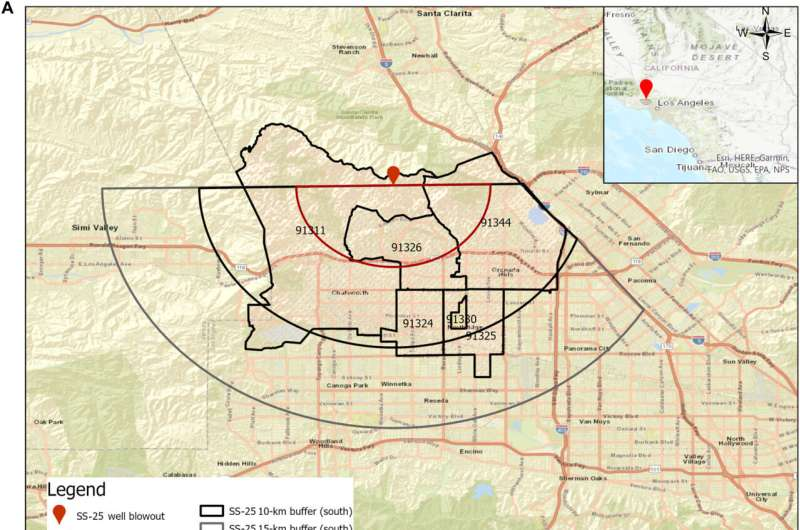

It’s been a decade since the Aliso Canyon gas blowout, one of the most catastrophic methane leaks in U.S. history. What began on an October evening in 2015, in the hills above Porter Ranch, Los Angeles, turned into a 112-day environmental disaster that forced thousands from their homes, sparked new regulations, and raised serious questions about America’s reliance on underground natural gas storage.

Today, ten years later, the scars are still visible—both on the land and among the people who lived through it. And despite early promises of closure, the Aliso Canyon facility remains open, operating under stricter conditions but continuing to store enormous amounts of natural gas.

Let’s break down exactly what happened, what’s changed, and why this disaster remains a critical reminder for U.S. energy policy and climate action.

The Incident That Shook Los Angeles

The Aliso Canyon gas storage facility sits in the Santa Susana Mountains, just north of Los Angeles. Originally an oil field drilled in the late 1930s, it was later converted into a massive underground gas storage site in the early 1970s. Utilities often use depleted oil fields like this to store natural gas under pressure, pumping it down for later use during peak demand seasons.

In October 2015, the facility was being filled for the winter heating season. Southern California Gas Company (SoCalGas) was using intense pressure to pump gas into the system—through wells that were, by then, over 60 years old. One of these wells, SS-25, had a corroded metal casing. That casing failed, and what began as a minor leak quickly escalated into a massive blowout.

Over the next 112 days, more than 100,000 to 120,000 tons of methane and other hydrocarbons escaped into the atmosphere. Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas, roughly 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period. The Aliso Canyon leak was so large it temporarily increased California’s methane emissions by 25%.

Infrared footage released by the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) showed a geyser-like plume of invisible gas shooting into the air. The leak was eventually stopped in February 2016, after a relief well was drilled to intercept and plug the damaged one.

Health and Community Impacts

The effects on nearby residents were immediate and severe. People in Porter Ranch and surrounding neighborhoods reported nausea, headaches, nosebleeds, burning eyes, and heart palpitations. Many described a strong odor of gas and chemicals. Over 8,000 households had to be temporarily relocated. Two schools shut down and were moved to new locations for months.

A UCLA study published in September 2025 found that women living within 6.2 miles downwind of the blowout during pregnancy had a 50% higher chance of delivering low birth-weight babies. Other studies have linked exposure to chemicals such as benzene, hexane, and toluene—found in the gas samples—to potential long-term respiratory and neurological effects.

SoCalGas has paid around $2 billion in settlements related to the disaster, including a $120 million consent decree with the state of California to fund methane mitigation, air monitoring, and public health research. About $25 million was set aside for a long-term health study led by UCLA researchers, whose findings are still pending.

Despite these settlements, residents argue that justice remains incomplete. Many have moved away, selling homes at a loss due to lingering health fears. Others continue to experience chronic respiratory symptoms.

The Ongoing Role of Aliso Canyon

After the blowout, then-Governor Jerry Brown called for the permanent closure of Aliso Canyon by 2027. His successor, Gavin Newsom, reaffirmed that goal. But as of late 2025, the facility is still operational—and may continue into the 2030s.

In December 2024, California regulators voted to allow SoCalGas to expand storage capacity from 41 billion cubic feet to 68.6 billion cubic feet, citing the need for energy reliability and affordable rates.

SoCalGas argues that Aliso Canyon remains critical for grid stability, feeding 17 power plants and supplying energy during times when renewable sources like wind and solar can’t meet demand. Natural gas still provides about 40% of California’s electricity.

Company officials say the facility has undergone major safety upgrades, including:

- Replacing inner steel tubing in every active well

- Installing real-time pressure monitoring

- Conducting visual inspections four times daily

- Implementing continuous ambient methane monitoring

They note that the maximum pressure limit has been reduced to 3,183 psi from 3,600 psi before the blowout.

Still, residents and environmental groups remain skeptical. They point out that the facility operated for two years after the disaster without issue—proof, they argue, that it isn’t essential to the energy grid.

Policy and Regulatory Changes

The Aliso Canyon disaster became a turning point for methane regulation and underground storage safety in the U.S.

In response, California enacted the strongest underground gas storage rules in the nation, requiring:

- Regular integrity testing of wells

- More robust well construction standards

- Continuous methane monitoring

- Improved emergency response planning

At the federal level, Congress directed the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) to create national safety standards for underground gas storage. In 2016, PHMSA adopted new rules based on American Petroleum Institute best practices, which were strengthened again in 2025.

Before this, many states had no regulations at all for gas storage facilities. Experts now say the system is much safer overall, but aging infrastructure remains a concern. Upgrading older wells can be slow and expensive, often leaving ratepayers responsible for the costs.

Technological and Scientific Advances

One silver lining from the disaster has been innovation. Infrared imaging of methane leaks, which was relatively new in 2015, is now standard practice. The California Air Resources Board began conducting large-scale aerial methane surveys in 2016, identifying the state’s biggest emission sources.

We now also have satellite systems and remote sensors capable of detecting methane “super-emitters” worldwide. However, despite better detection, global methane concentrations continue to rise, mainly from oil and gas operations, landfills, and agriculture.

Scientists have also learned that natural gas isn’t as “clean” as once believed. While methane is the main component, gas from underground storage often contains hazardous air pollutants, including carcinogens like benzene. This contamination happens when gas mixes with depleted oil and subsurface materials.

Researchers now argue that gas companies should be required to disclose gas composition so that emergency responders know exactly what chemicals are being released during leaks.

The Bigger Picture: Methane and Climate

Methane accounts for about a quarter of all human-caused global warming. Its short-term potency makes it a key target for climate policy.

In 2024, the Biden administration introduced the first comprehensive methane pollution rules, including fines on oil and gas developers for excessive emissions. However, the Trump administration in 2025 revoked the measure, calling it an unnecessary tax.

This policy back-and-forth highlights the tension between climate goals and energy reliability. California aims for 100% carbon neutrality by 2045, but reaching that target will require major transitions away from fossil fuels—including natural gas.

SoCalGas insists it supports the state’s climate vision through renewable natural gas, hydrogen, and other low-carbon technologies. Still, critics argue that maintaining Aliso Canyon undermines that commitment.

Looking Forward

The Aliso Canyon blowout remains a sobering reminder of what happens when outdated fossil fuel infrastructure meets modern environmental expectations.

It forced California—and the country—to rethink how we store and manage natural gas. It led to better monitoring, stricter oversight, and technological progress. But the underlying dependence on fossil fuels persists, and so do the risks.

For residents of Porter Ranch, the memories haven’t faded. Many continue to demand accountability, closure, and transparency. Whether the state will finally retire Aliso Canyon—or continue to rely on it for another decade—remains to be seen.

Research Reference:

Study on pregnancy and low birth weight: Science Advances, DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adr6684