Archaeologists Discover 1,000-Year-Old Native American Farms Hidden Beneath Michigan Forests

Beneath the thick forests of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, archaeologists have uncovered something astonishing — a massive ancient farming system built and maintained by the ancestral Menominee communities over 1,000 years ago. The discovery, led by researchers from Dartmouth College, challenges nearly everything experts thought they knew about early agriculture in the northern Great Lakes region.

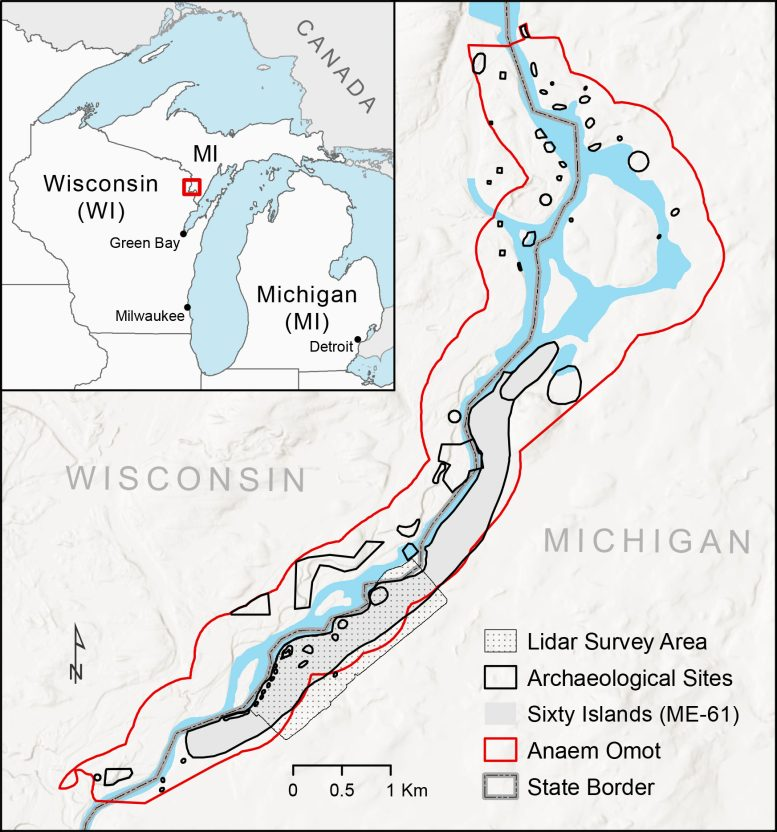

This site, known as Sixty Islands, sits along the Menominee River, straddling the border between Michigan and Wisconsin. The area’s cold climate, short growing season, and dense vegetation have long made it seem like an unlikely place for large-scale farming. But the new research shows that these Indigenous farmers developed an ingenious agricultural system that thrived for centuries — and may have been far larger and more complex than anyone imagined.

The Sixty Islands Discovery

At the heart of this breakthrough is a vast network of raised agricultural beds, sometimes called ridge fields, which were used for growing crops such as corn, beans, and squash — the traditional “Three Sisters” of Native American agriculture.

Researchers used drone-mounted LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) to peer beneath the forest canopy and reveal features invisible to the naked eye. LiDAR works by firing thousands of laser pulses at the ground and measuring how long they take to bounce back. This allows archaeologists to build a precise 3D map of the landscape, even through heavy vegetation.

The results were remarkable. The LiDAR scans showed that about 70% of the surveyed area was covered with ridged garden beds, each measuring between 4 and 12 inches tall. The survey covered roughly 330 acres, but researchers believe this represents only about 40% of the full site, meaning the true scale of farming could stretch across hundreds more acres still hidden beneath the trees.

The farming beds date back to roughly the 10th century (around the year 1000 CE) and were actively used and rebuilt until around 1600 CE. This period covers what archaeologists call the Late Woodland period, a time when Native American communities in the Great Lakes region were primarily thought to rely on small-scale gardening and foraging. The Menominee ridges suggest something far more advanced — an intensive agricultural system capable of supporting a large and organized community.

Advanced Farming in an Unlikely Place

Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is known for its long winters and rocky soils, conditions that make modern farming difficult even today. Yet, these ancient farmers were able to cultivate crops at the northern edge of maize’s growing range.

The Menominee farmers reshaped the land to make it fertile. Excavations revealed layers of charcoal, ceramic fragments (called sherds), and other household refuse mixed into the soil, suggesting that they enriched their fields using compost and burnt material. There’s also evidence that wetland soils were added to increase moisture and nutrients — an early form of soil management that resembles composting and raised-bed gardening techniques still used around the world today.

The ridges weren’t just practical; they were also ingenious adaptations to the local environment. The slightly elevated beds improved drainage in wet conditions while also retaining heat, helping crops grow in a region with a short and unpredictable summer.

These innovations allowed the Menominee to farm successfully for over six centuries, continuously rebuilding and maintaining their raised beds as part of a sophisticated and enduring agricultural tradition.

A Cultural Landscape Full of History

The Sixty Islands site is part of a broader ancestral Menominee region called Anaem Omot, meaning “Dog’s Belly” in the Menominee language. This area has long been known to contain burial mounds, ceremonial dance rings, and ancient village remains, but until recently, no one realized the extent of its agricultural landscape.

The site has a long research history. It was first mapped in the 1990s by archaeologist Marla Buckmaster of Northern Michigan University and later excavated by Jan Brashler of Grand Valley State University, who found and dated a corn cupule (the part of the cob that holds the kernels). These early studies hinted at ancient farming, but without modern tools, the full scale remained hidden.

That changed in 2023, when the Dartmouth-led team — invited by the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin — began a detailed drone-based LiDAR survey. The team worked closely with David Grignon, the tribe’s historic preservation officer, and the late David Overstreet, an archaeologist with the College of the Menominee Nation. Their collaboration ensured that the research respected tribal sovereignty and cultural heritage while using cutting-edge science to reveal the past.

LiDAR uncovered more than just the farming ridges. The scans revealed a circular dance ring, a rectangular foundation that may have been a colonial trading post, two 19th-century logging camps, and multiple burial mounds, including some that had been looted or thought destroyed decades ago. One newly documented mound even lies on private land owned by a mining company — a reminder of the delicate balance between archaeology, preservation, and modern land use.

Rethinking What We Know About Early Agriculture

The discovery at Sixty Islands challenges many long-held assumptions about Indigenous societies in North America. Archaeologists once believed that large-scale, organized agriculture was limited to more temperate or tropical regions like the Mississippi Valley or Mesoamerica. But the Menominee system shows that complex farming could thrive even in northern, forested environments.

The sheer size of the Sixty Islands system — which researchers estimate is ten times larger than previously thought possible in this region — suggests a level of community cooperation and organization not typically associated with small, egalitarian Woodland societies. While these communities didn’t have kings or centralized states, they clearly had the knowledge, coordination, and persistence to reshape the landscape over centuries.

This discovery also forces researchers to reconsider the environmental history of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. For centuries, this area was believed to have been continuously forested before European logging began. But if the Menominee cleared and maintained hundreds of acres of farmland for 600 years, it means that much of the forest regrew only after Indigenous agriculture declined — fundamentally altering how we understand the region’s ecological past.

The Power of LiDAR in Archaeology

One of the most fascinating aspects of this discovery is the technology behind it. LiDAR has become a game-changer in archaeology, especially in heavily forested regions where ancient features are hidden by vegetation.

Traditional aerial photography and satellite imagery can’t see through tree canopies. But LiDAR’s laser pulses can — and they can map the ground’s surface with incredible accuracy. In this case, using drone-based LiDAR allowed researchers to fly lower than standard airplane surveys, capturing high-resolution data that revealed fine details, including faint ridges and mounds that older LiDAR datasets missed.

This isn’t the first time LiDAR has transformed archaeology. The technology has revealed lost Mayan cities in Central America, hidden temples in Cambodia, and ancient road systems across the Amazon. Now, it’s helping scientists rediscover ancient agricultural landscapes in North America that were erased by centuries of natural regrowth and modern land use.

The success at Sixty Islands suggests that many more hidden Indigenous landscapes could still be waiting to be found across the eastern United States.

The Menominee: Farmers, Engineers, and Innovators

The Menominee people, whose descendants still live in Wisconsin today, have deep connections to this land. For thousands of years, they lived along the rivers and forests of the Great Lakes, hunting, fishing, gathering, and — as this research proves — farming intensively.

Their traditional knowledge of ecology, soil, and seasonal rhythms made them excellent land stewards. The raised fields show that the Menominee understood how to balance human needs with environmental limits, maintaining productivity over centuries without exhausting the soil.

The collaboration between the Menominee Tribe and modern researchers has been central to this project. It’s an example of community-engaged archaeology, where Indigenous voices help shape research questions, guide interpretations, and ensure that discoveries are shared respectfully.

What the Discovery Means for the Future

The Sixty Islands site provides a rare, well-preserved glimpse into pre-colonial farming systems in the northern U.S. Most such landscapes have been erased by plowing, urbanization, or industrial logging. That makes this discovery not only significant for archaeology but also for understanding how Indigenous knowledge shaped North America’s landscapes long before European colonization.

It also highlights how our assumptions about “wilderness” often ignore the deep history of human activity. Many forests once thought to be untouched may actually be reforested farmlands, shaped by centuries of Indigenous cultivation and management.

The team plans to continue surveying the Sixty Islands site and neighboring areas along the Menominee River to locate ancestral villages and document the full extent of this ancient agricultural network.

This research isn’t just rewriting history — it’s reconnecting stories that were buried under layers of soil and forest for a millennium.

A Broader Look: Indigenous Farming Across the Americas

The Menominee fields are part of a much larger story of Indigenous agricultural ingenuity across the Americas. Long before European colonization, Native societies developed diverse farming systems suited to their environments:

- Maya farmers built raised fields in swampy lowlands.

- Andean communities in South America constructed terraced farms high in the mountains.

- Mississippian cultures in the American Midwest created vast agricultural villages supported by maize cultivation.

These systems show that Indigenous peoples were skilled engineers and ecologists, adapting their farming methods to extreme climates and terrains. The Menominee fields now join this legacy as one of the most complete ancient agricultural systems ever found in the eastern United States.

Research Reference

Research Paper: Archaeological evidence of intensive indigenous farming in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, USA (Science, June 5, 2025).

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.ads1643