Cleaner Ship Fuel Is Quietly Reducing Lightning in the World’s Busiest Shipping Lanes

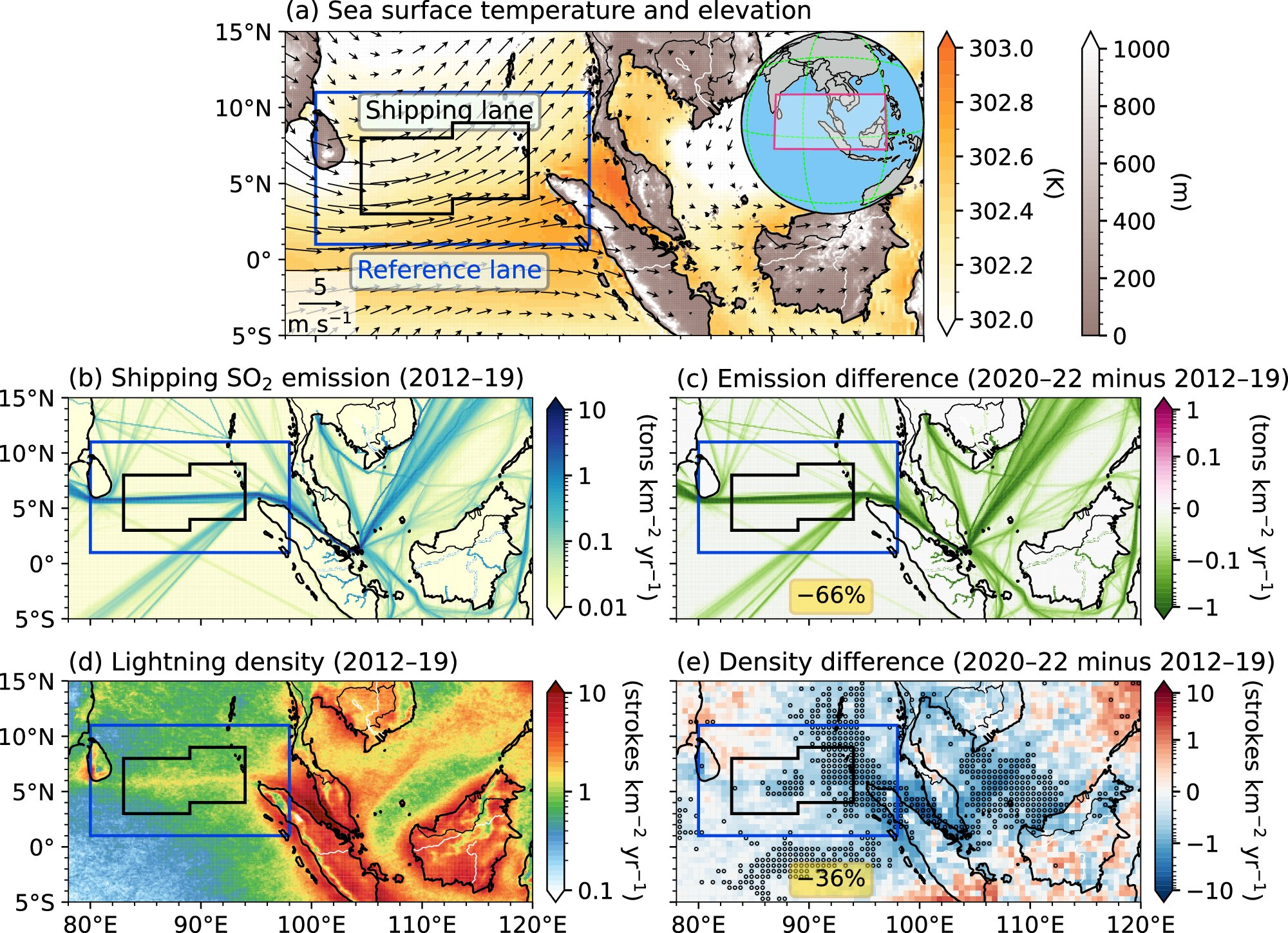

Global efforts to clean up ship fuel are having an unexpected side effect far above the ocean’s surface: less lightning. New climate research shows that stricter limits on sulfur emissions from oceangoing vessels are linked to a significant drop in lightning activity along some of the world’s busiest maritime routes, particularly in the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea.

The findings come from a detailed observational study published in the journal npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, led by researchers at the University of Kansas. The work connects changes in shipping fuel standards introduced in 2020 with measurable shifts in cloud properties, storm strength, and lightning frequency.

A Natural Experiment Triggered by New Shipping Rules

In 2020, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) introduced a major regulation that capped the sulfur content in marine fuel. This rule, often referred to as IMO 2020, reduced the allowable sulfur concentration from 3.5% to 0.5% worldwide. The goal was straightforward: cut air pollution from ships, especially sulfur dioxide (SO₂), which contributes to acid rain and harms human health.

What followed was a dramatic drop in sulfate aerosol emissions from international shipping. In some regions, including the Bay of Bengal, sulfate emissions fell by roughly 70% within a short period.

For climate scientists, this sudden and widespread change created something rare: a real-world experiment. Instead of relying only on climate models, researchers could directly observe how the atmosphere responded when a major pollution source was sharply reduced.

Why the Bay of Bengal Stood Out

The Bay of Bengal turned out to be an ideal region to study these effects. It combines two critical factors:

- Extremely heavy shipping traffic, which historically released large amounts of sulfate aerosols into the marine atmosphere

- Strong natural convection, meaning the region regularly produces tall storm clouds capable of generating lightning

Before 2020, satellite and lightning network data consistently showed enhanced lightning activity directly over shipping lanes in this region. These patterns were not random—they closely followed major maritime routes.

After the sulfur cap took effect, that enhancement weakened.

Measuring Lightning from Space and the Ground

To track lightning, the researchers used data from the World Wide Lightning Location Network (WWLLN), a global system operated by the University of Washington. This network detects individual lightning strokes with high spatial resolution and has been collecting data since the early 2000s.

The study analyzed lightning density, defined as the number of lightning strokes per square kilometer per year, across multiple time periods:

- A long-term pre-regulation baseline from 2012 to 2019

- A shorter immediate pre-regulation window from 2016 to 2019

- A post-regulation period from 2020 to 2023

The results were striking. Along major shipping lanes in the Bay of Bengal, lightning stroke density dropped by about 36% after 2020 compared to pre-regulation levels.

Separating Shipping Effects from Weather

Of course, weather patterns change naturally from year to year. To isolate the role of shipping emissions, the researchers used a statistical approach that compared actual observations with a counterfactual scenario—an estimate of what lightning activity would have looked like if shipping emissions had not changed.

This involved advanced techniques such as regression kriging and machine learning models, trained using nearby ocean regions with similar meteorology but less shipping influence.

Their analysis showed that while part of the lightning reduction could be explained by natural variability, a substantial portion was directly linked to reduced ship emissions. Conservatively, the study estimates that shipping pollution previously contributed at least 17% of lightning activity in the Bay of Bengal shipping corridor.

What Sulfur Aerosols Have to Do with Lightning

At first glance, the idea that dirty fuel could increase lightning might seem counterintuitive. The connection lies in cloud microphysics.

When ships burn high-sulfur fuel, they emit sulfate aerosols into the atmosphere. These tiny particles act as cloud condensation nuclei, which influence how clouds form and evolve.

Here’s how the process works:

- More sulfate aerosols lead to many smaller cloud droplets

- Smaller droplets are less likely to fall as rain, allowing clouds to persist longer

- Longer-lived clouds can grow taller and colder, increasing ice crystal formation

- Interactions between ice crystals, graupel, and supercooled water are key drivers of lightning generation

With fewer sulfate aerosols after 2020, clouds over shipping lanes showed measurable changes. Satellite data revealed larger low-cloud droplets, lower cloud-top heights, and reduced indicators of strong convection—all conditions associated with less frequent lightning.

Similar Patterns in Other Shipping Regions

The Bay of Bengal was not the only area affected. The researchers also examined other major maritime corridors.

- In the South China Sea, they found a similar decline in lightning activity closely aligned with shipping routes

- In the Red Sea, the signal was present but weaker, likely due to differences in regional weather patterns and shipping density

Together, these regions strengthened the case that the observed changes were not isolated coincidences but part of a broader, emission-driven pattern.

Safer Seas, but a More Complicated Climate Picture

Reduced lightning could be considered a practical benefit for maritime operations. Lightning poses risks to ships, onboard electronics, and crew safety, and can disrupt navigation and visibility during storms.

However, the study also highlights a more complex climate trade-off.

Sulfate aerosols have a cooling effect on Earth’s climate because they reflect sunlight and brighten clouds. With fewer sulfate particles in the atmosphere, clouds can become darker and less reflective, allowing more solar energy to be absorbed.

Previous research by the same group suggests that the decline in shipping-related sulfate aerosols may have contributed to the record-breaking global temperatures observed in 2023 and 2024. In other words, cleaner air can come with a short-term warming effect.

What This Means for Climate Science Going Forward

One of the key takeaways from this study is the importance of high-resolution observations. Global climate models often struggle to accurately represent cloud processes, especially in the boundary layer over oceans.

To address this, the researchers plan to use regional climate models with much finer spatial detail in future work. These models can better resolve low-level clouds, such as stratocumulus, which play a major role in regulating Earth’s temperature.

The team also plans to investigate long-term lightning trends in Asia, where many countries began reducing sulfate emissions around 2010 through clean air policies. If similar lightning declines are found over land, it could further confirm the link between aerosol reductions and storm electrification.

Why This Research Matters Beyond Lightning

Lightning is more than just a dramatic weather phenomenon. It influences:

- Atmospheric chemistry, including the production of nitrogen oxides

- Wildfire ignition, especially in dry regions

- Global electrical circuits that connect thunderstorms worldwide

Understanding how human activities subtly reshape these processes helps scientists better predict future climate behavior—and anticipate unintended consequences of environmental regulations.

In this case, a policy designed to clean up ship exhaust ended up revealing just how deeply connected pollution, clouds, storms, and climate really are.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41612-025-01256-w