Coastal Gray Wolves Are Hunting Sea Otters — Scientists Are Trying to Understand Why

On Alaska’s Prince of Wales Island, researchers have discovered that gray wolves are preying on sea otters, a behavior that has taken scientists by surprise. These coastal wolves are venturing beyond their traditional terrestrial hunting grounds and turning to the marine environment for food — a shift that could reshape our understanding of how land and sea ecosystems are connected.

This research, led by Patrick Bailey, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Rhode Island, is uncovering new insights into how gray wolves are adapting their hunting strategies and diets in unexpected ways. Bailey’s work suggests that wolves may not only influence forest ecosystems, as has long been known, but also the delicate balance of coastal marine ecosystems.

Wolves Taking to the Coast

Gray wolves are known for their adaptability, but actively hunting sea otters is something new. Historically, wolves have hunted large land mammals like deer, moose, and caribou. On Prince of Wales Island, however, Bailey and his team have found that wolves are hunting marine mammals, a dietary change that could alter both predator behavior and ecosystem dynamics.

This discovery hints at a re-emerging relationship between the two species. Sea otters were once abundant along the Pacific Coast, but centuries of overhunting during the fur trade nearly wiped them out. As otters make a comeback, wolves seem to be re-establishing a long-lost predator-prey connection.

How Researchers Are Studying the Wolves

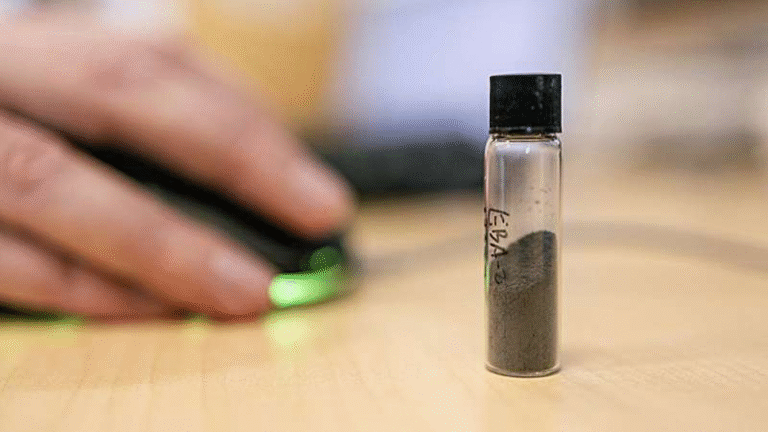

Bailey’s team is using stable isotope analysis and trail cameras to investigate this phenomenon. The isotope analysis involves examining wolf teeth samples from museum collections and recently deceased wolves. Much like tree rings, wolf teeth contain growth layers that record their diet over time. By analyzing these layers, scientists can determine how much marine prey individual wolves consumed throughout their lives.

Trail cameras have also been strategically placed along the Alaskan coast. Bailey and his team have collected over 250,000 images since last winter, documenting wolf and sea otter interactions. These photos could finally reveal how wolves capture sea otters, a question that has remained unanswered.

The first footage from earlier studies was too low in resolution to show the exact hunting behavior, but new high-definition trail cameras are expected to provide clearer evidence.

Bailey isn’t working alone. He’s collaborating with Gretchen Roffler, a biologist with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, and Michael Kampnich, a local research technician with deep knowledge of the island’s terrain and wildlife. Their on-the-ground expertise has been crucial for navigating the remote, rugged landscape where these elusive predators roam.

Why the Behavior Matters

Wolves play a critical ecological role by regulating prey populations and maintaining balance within ecosystems. Traditionally, this role has been understood only within terrestrial food webs. But Bailey’s research raises new questions about how wolves influence aquatic ecosystems.

If wolves are now feeding on marine species, they could be transferring nutrients — and even contaminants — between the land and sea. In this way, wolves may serve as a bridge between two ecosystems that were previously thought to operate largely independently.

Mercury and the Health Risk for Wolves

One of the more concerning findings comes from Roffler’s recent research on methylmercury, a toxic form of mercury found in sea otters. Wolves that eat sea otters are showing dramatically higher mercury levels than inland wolves — in some cases up to 278 times higher.

This is significant because methylmercury can lead to serious health problems, including reproductive issues, neurological effects, and behavioral changes. The discovery suggests that as wolves rely more on marine prey, they may be exposing themselves to dangerous levels of marine pollutants.

Bailey and Roffler are currently examining wolf liver samples to assess how mercury levels vary between coastal and inland populations. The results will help determine whether this dietary shift poses long-term risks to wolf populations and how toxins might be moving up the food chain.

The Unknowns: How Do Wolves Catch Sea Otters?

While it’s now clear that wolves are eating sea otters, how they manage to catch them remains a mystery. Sea otters are agile swimmers, spending most of their time in water, so wolves likely target them when they come ashore to rest or move between coastal areas.

Researchers suspect wolves may ambush otters on beaches or scavenge carcasses washed up by tides. The new trail cameras on Prince of Wales Island are expected to capture these moments for the first time in detail.

Studying these animals is no small feat. Wolves are intelligent, elusive, and wary of humans. Combined with Alaska’s dense forests and harsh terrain, tracking and observing them becomes an enormous challenge. That’s why Bailey’s collaboration with local experts has been vital for understanding how these predators operate in such an extreme environment.

Ecosystem Implications

The implications of this new behavior stretch far beyond wolves and sea otters. Sea otters are known as keystone species — their presence helps control sea urchin populations, which in turn allows kelp forests to thrive. If wolves significantly reduce otter numbers, it could lead to an increase in sea urchins and a decline in kelp ecosystems.

Kelp forests are vital for coastal health, providing habitat for fish and absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. This means a change in wolf diet could indirectly affect marine biodiversity and carbon storage in coastal ecosystems.

Additionally, wolves dragging sea otter carcasses inland may deposit marine nutrients into terrestrial environments, influencing plant growth and soil composition. This kind of cross-ecosystem nutrient transfer is still poorly understood but could have significant ecological consequences.

Historical and Geographical Context

The presence of wolves along Alaska’s coasts is not new. Similar behavior has been reported elsewhere, such as on the Katmai coast, where wolves have been observed hunting harbor seals and sea otters. What’s remarkable is how consistently this marine hunting pattern is appearing in different coastal wolf populations.

Historically, before the fur trade decimated sea otter populations, wolves may have hunted them regularly. If that’s the case, what Bailey’s team is observing might not be a “new” adaptation but rather a re-emergence of an ancient predator-prey relationship.

Bailey’s research also extends to comparing skull morphology between coastal and inland wolves, examining whether coastal populations have developed physical adaptations that help them thrive in marine environments. His study includes specimens from Canada, Newfoundland, and Labrador, in collaboration with the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

This research highlights how flexible and intelligent wolves are as predators. Their ability to adapt to changing food availability shows just how resilient they can be. It also challenges our assumptions about how strictly “land” and “sea” ecosystems are separated.

From a conservation perspective, these findings urge scientists and policymakers to consider the interconnectedness of ecosystems. Protecting wolves and sea otters now means understanding how their behaviors and environments overlap — and how human activity, such as pollution, can affect both.

As for Bailey and his team, they plan to continue their work for several more years, returning to Prince of Wales Island for more field studies. Their goal: to fully document how wolves are adapting to marine life and what that means for the future of coastal ecology.

Research Reference:

“Switching to marine prey leads to unprecedented mercury accumulation in coastal wolves” – Science of The Total Environment, 2025