Deep Earth Faults Can Heal Themselves Within Hours After Seismic Movement

Scientists have uncovered a fascinating process happening deep beneath Earth’s surface: rocks along major geological faults can rapidly heal after seismic movement. This discovery—led by researchers at the University of California, Davis (UC Davis)—suggests that faults located kilometers below the surface can regain strength in just a few hours. The finding adds an important new layer to how we understand earthquakes, slow slip events, and the physics of fault behavior.

This research, published in Science Advances, demonstrates that fault healing is not a slow, centuries-long recovery as traditionally believed. Instead, under the extreme pressures and temperatures found deep in subduction zones, the mineral grains inside fault rocks can bond together again surprisingly quickly. The results challenge long-held assumptions in earthquake science and may influence how we think about seismic risk.

What the Scientists Discovered About Fault Healing

Researchers Amanda Thomas and James Watkins, both from UC Davis, wanted to understand how sections of faults involved in slow slip events can move repeatedly within short timespans. Slow slip events—often called “slow earthquakes”—release stress gradually over days, weeks, or months rather than in sudden violent shaking. They are common in subduction zones like the Cascadia Subduction Zone in the Pacific Northwest, where the Juan de Fuca plate slides beneath the North American plate.

The puzzling behavior they focused on is this: the same section of a deep fault can slip again within hours or days after a previous slip. For that to happen, the fault must somehow regain strength quickly enough to resist movement and then store new stress. Scientists have long been unsure how this was possible.

The new study provides a clear explanation: deep faults can cement themselves back together. The process involves mineral grains fusing under extreme conditions, essentially creating a kind of quick-setting geological glue.

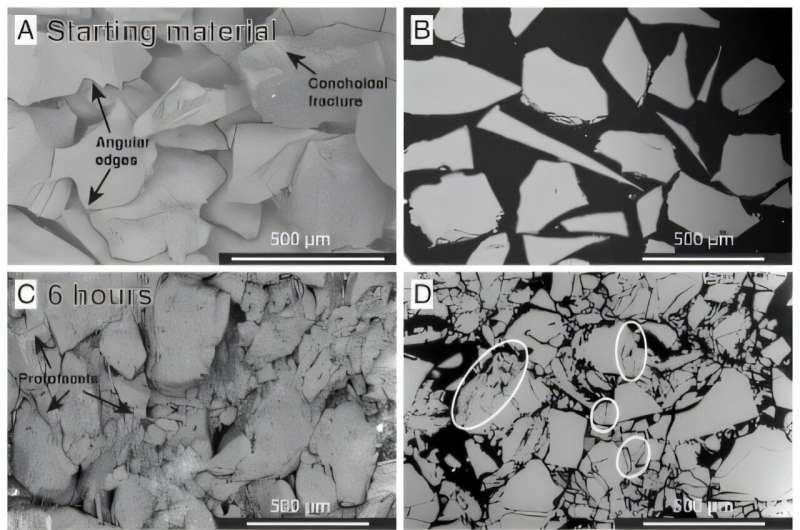

Thomas and Watkins carried out laboratory experiments using powdered quartz—the type of pulverized rock commonly found along faults. They packed the powder into small silver cylinders, welded the containers shut, and placed them into high-pressure, high-temperature systems that replicate deep-crust conditions. The samples were subjected to:

- 1 Gigapascal of pressure (about 10,000 times atmospheric pressure)

- 500 degrees Celsius

These are the conditions expected roughly 30–40 kilometers beneath the surface in major subduction zones.

After “cooking” the cylinders for six to 24 hours, the scientists measured changes in how sound waves traveled through the samples, which reveal how tightly the mineral grains are bonded. They then opened the cylinders and examined the rock under a scanning electron microscope. What they found was unmistakable: the loose quartz grains had fused together, forming cohesive, welded material. The rock showed substantial strength recovery in just a few hours.

This rapid cementation gives researchers a physical explanation for how slow slip events can recur so quickly. It also indicates that cohesion—how well the rocks bond at a microscopic level—may play a much larger role in fault dynamics than previously thought.

Why This Matters for Understanding Earthquakes

The idea that faults could heal within hours changes how scientists think about fault mechanics.

Traditionally, models of earthquake behavior have focused on friction, stress loading, and fluid pressure, but cohesion has often been neglected. In many simulations, fault zones are treated as surfaces that slide, build stress, and eventually break again after long periods.

However, the new study shows that faults can regain strength fast enough to influence the timing of slow slip cycles. This process may also affect how large earthquakes behave, especially in regions where deep slow slip events occur before or after major quakes.

Another important detail: slow slip events interact with tidal forces—the subtle gravitational pull from the sun and moon that causes daily land deformation. The fact that tidal stress can influence when slow slip events happen implies that the fault must be strong enough to respond to tiny stress fluctuations. Rapid healing provides a mechanism for that strength to return quickly.

Although the research focuses on deep faults—those at high pressure and temperature—it raises the possibility that similar cementation processes could matter at shallower depths too. Those shallower faults are the ones responsible for destructive earthquakes. If healing occurs there as well, it could influence how faults accumulate stress between quakes.

Understanding Slow Slip Events and Their Role in Fault Behavior

Since slow slip events were first identified around 2002, scientists have learned that they play a major role in how subduction zones behave. Unlike regular earthquakes, slow slip events don’t create strong shaking, so people rarely notice them. But they still involve centimeters of movement across large sections of fault—movements that can span hundreds of kilometers.

Slow slip events have been documented worldwide, including:

- Cascadia (U.S. Pacific Northwest)

- Hikurangi Margin (New Zealand)

- Nankai Trough (Japan)

- Mexico’s subduction zones

They often repeat on cycles ranging from months to years. The new UC Davis study suggests that rapid fault healing could be key to understanding these cycles.

This discovery also connects small-scale mineral processes with large-scale tectonic behavior. According to the research team, the way quartz grains weld together under pressure may help explain how faults transition between locked, slipping, and re-locked states.

The Role of Quartz in Fault Zones

Quartz is one of the most abundant minerals in the Earth’s crust, and it is common in fault gouge—the ground-up rock created by repeated fault movement.

Quartz has several properties that make it especially relevant:

- It deforms under high pressure and temperature.

- It can dissolve and re-precipitate, aiding cementation.

- Its grains can weld together at elevated temperatures.

Under the conditions used in the experiment, quartz grains essentially sinter together, similar to how powdered ceramics are fused in manufacturing. This welding increases the mechanical strength of the material—exactly what faults need to re-strengthen after slipping.

If similar processes occur in real subduction zones, then the Earth is constantly repairing and reconfiguring its deepest fault networks.

What This Means for the Future of Earthquake Science

The biggest takeaway from this study is that earthquake models may need updating.

Fault healing has usually been assumed to occur slowly, controlled by chemical reactions over long timescales. With new evidence that healing can happen within hours deep underground, scientists may need to revise their models of:

- How stress accumulates

- How faults transition between slipping and locked states

- How slow slip events influence major earthquakes

- How subduction zones prepare for megathrust earthquakes

The study also encourages researchers to explore similar healing processes in other minerals besides quartz and in fault zones with natural fluid mixtures. It opens the door to further experiments on mixed-rock systems, which more closely represent real faults.

Research Reference

Rapid Fault Healing From Cementation Controls the Dynamics of Deep Slow Slip and Tremor

https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adz2832