Disinfecting Drinking Water Can Create Potentially Toxic Byproducts and a New AI Model Is Helping Scientists Find Them

Disinfecting drinking water is one of the most important public health advances ever achieved. By killing bacteria, viruses, and parasites, water treatment has prevented massive outbreaks of deadly diseases such as cholera, typhoid, and dysentery. Even water that looks crystal clear can carry dangerous pathogens, so disinfection remains essential for keeping people safe—especially children, older adults, and those with weakened immune systems.

However, scientists have long known that water disinfection comes with a trade-off. The chemicals commonly used to kill pathogens, such as chlorine and chloramine, do not simply disappear after doing their job. Instead, they can react with naturally occurring organic matter in water and create compounds known as disinfection byproducts, or DBPs. Some of these byproducts may pose risks to human health, and researchers are now using artificial intelligence to better understand which ones matter most.

How Disinfection Byproducts Form in Drinking Water

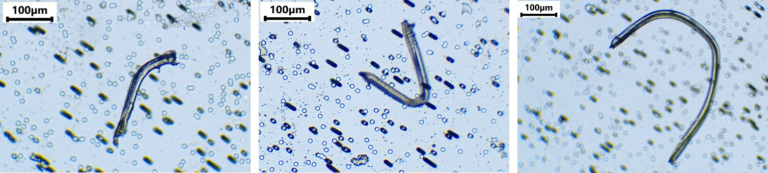

Natural water sources like rivers, lakes, and underground aquifers contain small amounts of organic material. This material is often referred to as dissolved organic carbon, and it comes from decaying plants, soil runoff, and other natural processes. When disinfectants such as chlorine are added to water, they react not only with harmful microbes but also with this organic matter.

The result is the formation of hundreds of different chemical byproducts, many of which are still poorly understood. Scientists have identified certain DBPs that are already linked to health concerns. Among the best-known examples are trihalomethanes (THMs) and haloacetic acids (HAAs), which have been associated with increased bladder cancer risk and developmental issues during pregnancy.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency currently regulates 11 specific disinfection byproducts, setting safety limits for how much can be present in drinking water. But research over the years has identified several hundred additional DBPs that are not regulated at all. Some of these unregulated compounds could potentially be more toxic than the ones already on the EPA’s radar.

Why Studying DBPs Is So Difficult

Understanding the health effects of disinfection byproducts is not straightforward. Traditional toxicity testing requires laboratory experiments that expose cells or organisms to chemicals under controlled conditions. These tests are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and expensive, which makes it nearly impossible to study hundreds or thousands of compounds individually.

Because of these limitations, scientists have struggled to keep up with the sheer number of DBPs that can form under different water treatment conditions. This gap in knowledge means regulators may not yet know which compounds deserve closer scrutiny or potential regulation.

How Artificial Intelligence Is Changing the Picture

To address this challenge, researchers at Stevens Institute of Technology developed a new AI-based machine learning model designed to predict the toxicity of disinfection byproducts. The project was led by environmental engineer Tao Ye, along with his Ph.D. student Rabbi Sikder, in collaboration with Peng Gao from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The team began by collecting toxicity data from existing scientific studies. They gathered detailed information on 227 known chemicals, including their molecular structures, exposure conditions, and experimentally measured toxicity values. This dataset served as the foundation for training the AI model.

Once trained, the model was able to analyze chemical structures and predict toxicity for 1,163 disinfection byproducts that have little or no experimental data available. The results were eye-opening. Some of the predicted toxicity values were two to ten times higher than those of certain DBPs that are already regulated by the EPA.

The findings were published in the journal Environmental Science & Technology Letters under the title Multi-Endpoint Semi-Supervised Learning Identifies High-Priority Unregulated Disinfection Byproducts. The study highlights how AI can rapidly screen large numbers of chemicals and help scientists prioritize which ones need further investigation.

What This Means for Tap Water Safety

Hearing about toxic byproducts in drinking water naturally raises concerns, but researchers emphasize that there is no reason to panic. Your tap water is not suddenly unsafe. The large number of DBPs identified by the AI model represents all the compounds that could theoretically form under various conditions—not all of them are present in any single water supply.

Different regions use different disinfectants and have different types of organic matter in their source water. This means the mix of byproducts varies widely from place to place. The purpose of this research is not to alarm the public, but to support better regulation and smarter monitoring in the future.

By identifying which unregulated DBPs may be most harmful, scientists and policymakers can decide where to focus their attention. Over time, this could lead to updated safety standards and improved water treatment strategies that reduce risks even further.

How People Can Reduce DBPs at Home

For individuals who want to take extra precautions, there are simple steps that can help reduce disinfection byproducts in tap water. Household water filters, especially those containing activated carbon, are effective at removing many DBPs.

Another option is boiling water. Some disinfection byproducts are volatile, meaning they can evaporate when water is heated. Boiling allows these compounds to escape, lowering their concentration in the water you drink. Both methods are easy to use and widely accessible.

Why AI Is Becoming Essential in Environmental Science

This study is part of a broader trend toward using machine learning and AI in environmental research. As scientists face increasingly complex chemical mixtures and massive datasets, traditional methods alone are no longer enough. AI models can analyze patterns that would take humans years to uncover, offering faster insights into pollution, toxicity, and risk assessment.

In the context of drinking water, AI can help bridge the gap between what we know and what we still need to understand. Rather than replacing laboratory testing, these tools act as powerful screening systems, guiding researchers toward the most important questions to answer next.

The Bigger Picture of Water Disinfection

Despite the challenges posed by disinfection byproducts, it is important to remember that water disinfection saves lives. Before modern treatment systems, waterborne diseases regularly devastated communities. The goal of current research is not to move away from disinfection, but to make it even safer and more effective.

By combining chemistry, public health, and artificial intelligence, scientists are working to ensure that drinking water remains one of the safest resources we rely on every day.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.5c01145