Global Food Insecurity Measures May Be Missing One in Five Hungry People Worldwide

Global hunger numbers are often treated as hard facts, guiding billions of dollars in humanitarian aid and shaping international responses to food crises. But new research suggests those numbers may be far too low. According to a recent study led by researchers from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, global food insecurity assessments systematically underestimate acute hunger, potentially leaving tens of millions of people invisible to the systems designed to help them.

At the center of this issue is the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), the world’s most widely used framework for analyzing and classifying food insecurity. Humanitarian agencies depend on IPC analyses to decide where aid is needed, how urgently it is required, and how much funding should be released. The new findings challenge a long-held assumption within the humanitarian sector—that the IPC tends to exaggerate crises. Instead, the evidence points in the opposite direction.

How Global Hunger Is Officially Measured

The IPC was established in 2004 as a partnership among governments, UN agencies, NGOs, and research institutions. By 2024, its analyses were being used to allocate more than $6 billion in humanitarian aid every year. The system focuses on countries and regions already considered vulnerable due to chronic poverty, climate shocks, conflict, or political instability.

IPC assessments are conducted at the subnational level in roughly 30 countries worldwide. Teams of trained analysts review a wide range of data, including dietary quality and diversity, food prices, household income, weather conditions, conflict indicators, and health and nutrition statistics. This information is often incomplete or inconsistent, especially in regions experiencing active crises.

Based on this data, analysts classify each area using a five-phase scale:

- Phase 1: None or minimal food insecurity

- Phase 2: Stressed

- Phase 3: Crisis

- Phase 4: Emergency

- Phase 5: Catastrophe or famine

A key threshold in this system is Phase 3. When 20% or more of a population in a given area is classified as Phase 3 or above, it signals an urgent need for humanitarian assistance. This cutoff plays a crucial role in triggering international responses.

Why Researchers Took a Closer Look

Evaluating the accuracy of IPC analyses is not straightforward. The system is designed to anticipate near-term crises, not simply describe current conditions. If warnings are accurate and aid arrives in time, the worst outcomes may never occur. In that sense, a “correct” prediction can appear wrong because disaster was avoided.

Despite this complexity, researchers were invited by the IPC in 2021 to conduct an independent evaluation of how the system performs. The resulting study, published in Nature Food, represents one of the most comprehensive reviews of IPC data to date.

The research team examined nearly 10,000 subnational food security analyses conducted between 2017 and 2023, spanning 33 countries. These assessments covered 917 million individuals, with repeated analyses bringing the total number of observations to 2.8 billion person-rounds.

A Pattern of Conservative Classification

One of the most striking findings was a statistical pattern known as “bunching.” When researchers looked at how populations were distributed around the critical 20% Phase 3 threshold, they noticed that many areas were classified just below that cutoff.

This pattern appeared consistently across multiple countries with very different levels of food insecurity, suggesting it was not a coincidence or a country-specific issue. Instead, it pointed to a systematic tendency to err on the side of caution.

When IPC analysts face conflicting indicators—for example, when food price data suggests a worsening situation but nutrition data lags behind—they tend to adopt a more conservative classification. In practice, this often means assigning a phase that falls just short of triggering a crisis designation.

How Many People Are Being Missed?

Using the same underlying data available to IPC working groups, the researchers produced their own estimates of how many people were experiencing acute food insecurity.

Their results were stark. While official IPC figures identified 226.9 million people as being in Phase 3 or higher, the researchers estimated the true number to be 293.1 million. That difference—66.2 million people—represents roughly one in five individuals facing urgent hunger who may not be counted in global statistics.

In real-world terms, this gap matters enormously. Humanitarian aid budgets are already stretched thin, and classification thresholds directly influence funding decisions. If millions of people are not officially recognized as being in crisis, they are far less likely to receive timely assistance.

Hunger in a Broader Global Context

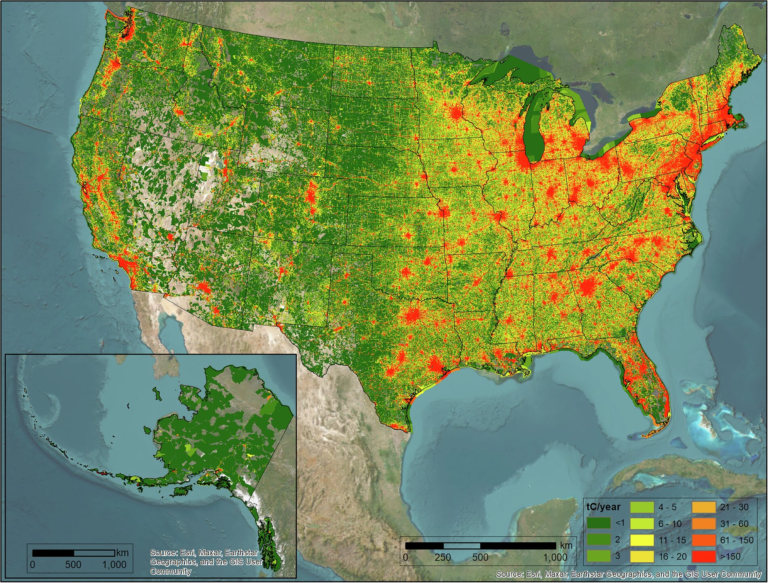

The study’s findings come against a troubling global backdrop. In 2023, an estimated 765 million people worldwide did not have enough food to meet their basic needs. Nearly one-third of them experienced acute food insecurity, meaning their lives or livelihoods were at immediate risk.

These numbers reflect the combined impacts of armed conflict, climate change, economic shocks, and persistent inequality. Extreme weather events disrupt agriculture, conflicts displace communities, and rising food prices push vulnerable households beyond their limits.

Accurate measurement is essential in this environment. When hunger is underestimated, the scale of the problem appears smaller than it truly is, making it easier for governments and donors to underestimate what is required to address it.

Can the System Be Improved?

The researchers are careful to stress that the IPC remains an essential and valuable tool. Its consensus-based approach, reliance on local expertise, and structured protocols have made it the global standard for food insecurity analysis.

However, the study highlights areas where improvements could help. Better data collection, especially in hard-to-reach regions, would reduce uncertainty. The authors also point to the potential role of machine learning and advanced statistical models to complement existing methods.

Importantly, they do not suggest replacing human judgment with automated systems. Instead, these tools could act as decision-support mechanisms, flagging cases where conservative bias might be leading to underclassification.

Why These Findings Matter

There is already a significant gap between humanitarian needs and available funding, and that gap is expected to widen as global aid budgets shrink. If current hunger estimates are systematically low, the true scale of unmet need is even larger than policymakers realize.

Recognizing that global hunger may be undercounted by millions reframes the conversation. It underscores the urgency of investing more resources, improving analytical tools, and ensuring that those on the brink of crisis are not overlooked because they fall just short of an arbitrary threshold.

In the end, food insecurity is not just a statistical problem. It is a matter of who gets seen, who gets counted, and who gets help—and who does not.

Research paper: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-025-01267-z