Global Plastic Waste Trade Is Directly Increasing Coastal Litter in Importing Countries, New Study Finds

A growing body of research has warned that plastic waste does not simply disappear once it leaves a country’s borders. A new academic study now provides strong evidence that international plastic waste trade is directly linked to higher levels of plastic litter along coastlines, especially in countries that import large volumes of waste and struggle with waste management systems.

The research, conducted by scholars at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and published in the journal Ecological Economics, uses nearly two decades of data to quantify how plastic waste imports translate into real, measurable pollution in coastal environments. Rather than relying on estimates or modeling alone, the study draws heavily on citizen-collected data, offering one of the clearest empirical connections between global waste trade and environmental harm.

Plastic Waste Versus Plastic Pollution

Plastic waste and plastic litter are often discussed as if they are the same thing, but the study makes an important distinction. Plastic waste refers to material that is collected and intended for recycling or processing. Plastic litter, on the other hand, is plastic that escapes waste systems and ends up polluting natural environments such as beaches, rivers, and coastlines.

Plastic beverage bottles are central to this issue. In countries like the United States, these bottles account for roughly half of all plastic collected for recycling. While much of this material is processed domestically, a significant portion is exported overseas as part of the global plastic waste trade.

The concern addressed by the researchers is straightforward: when plastic waste is shipped across borders, especially to countries with weaker infrastructure, the risk increases that some of it will leak into the environment during transport, storage, or processing.

A Data-Driven Look at Coastal Litter

To examine whether plastic waste imports actually lead to more pollution, the research team analyzed data from 90 countries between 2003 and 2022. They focused specifically on plastic bottles because these items are both widely recycled and easy to identify during cleanup efforts.

The litter data came from the Ocean Conservancy’s International Coastal Cleanup, a large-scale annual event where trained volunteers collect and record debris found along coastlines around the world. These records are aggregated at the country level and made publicly available, making them an unusually rich source of long-term environmental data.

Trade figures were sourced from the United Nations global trade database, allowing researchers to track how much plastic waste each country imported in a given year. To add further context, the study incorporated existing academic estimates of waste mismanagement rates, which measure how likely waste is to escape formal disposal systems.

What the Numbers Show

The results show a clear and consistent pattern. According to the analysis, a 10% increase in plastic waste imports is associated with a 0.6% increase in plastic bottles collected as coastal litter. While that percentage may seem small, the impact becomes significant when scaled up across millions of tons of waste.

In practical terms, the study finds that doubling plastic waste imports leads to approximately a 6% rise in coastal plastic bottle litter. Countries with poor waste management systems experienced even larger increases, indicating that infrastructure quality plays a major role in determining environmental outcomes.

This relationship held true across different regions and years, reinforcing the idea that plastic waste trade is not environmentally neutral, even when it is labeled as recycling material.

The Scale of the Global Plastic Waste Trade

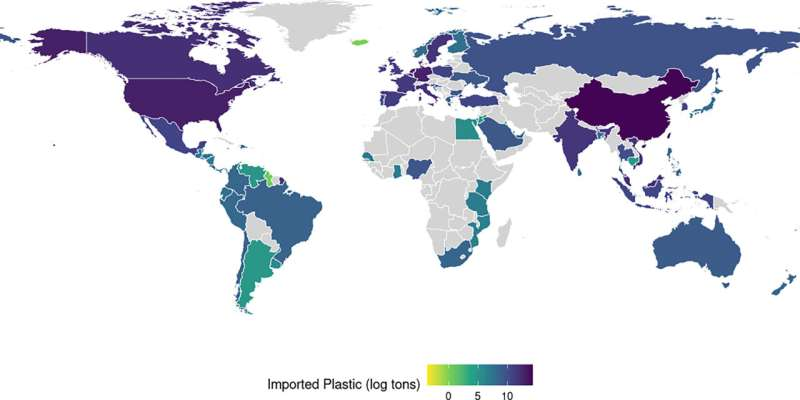

Globally, only about 2% of plastic waste is traded internationally, but that fraction represents a massive volume because global plastic production has increased dramatically over the past three decades. At its peak in 2014, international plastic waste trade reached 16 million metric tons, or roughly 35 billion pounds.

The trade largely flows from the global North to the global South, raising concerns about so-called pollution havens. These are countries that attract waste imports because they have lower environmental regulations, cheaper labor, or less developed waste management systems.

The Impact of China’s 2017 Import Ban

One of the most significant shifts in the plastic waste trade occurred in 2017, when China banned most plastic waste imports. For years, China had been the world’s largest destination for foreign plastic waste. After the ban, global plastic waste imports fell by approximately 73%.

However, the waste did not disappear. Instead, much of it was redirected to other countries, particularly in Southeast Asia. Nations such as Thailand and Malaysia saw sharp increases in plastic waste imports almost immediately after China’s policy change.

The study examined this period closely and found that a 1,000-ton increase in plastic waste imports between 2016 and 2017 was associated with a 0.7% increase in coastal plastic bottle litter in these countries. This provided a natural experiment that strengthened the overall findings.

Policy Responses and International Regulation

In response to the surge in waste imports, several countries that initially accepted redirected plastic waste later implemented their own import bans or restrictions. Another major policy shift came in 2019, when plastic waste was added to the Basel Convention, a global agreement regulating the trade of hazardous materials.

Countries that have ratified the Basel Convention are required to follow stricter guidelines for plastic waste trade, including prior informed consent and improved transparency. The United States has not ratified the Basel Convention, which continues to shape how U.S. plastic waste is traded internationally.

Why Trade Restrictions Alone Are Not Enough

While the study clearly shows that plastic waste imports contribute to coastal litter, it also highlights an important limitation. Reducing or banning trade alone will not eliminate plastic pollution. Coastal litter continues to exist even in countries that import little or no plastic waste.

The researchers emphasize that waste management systems matter just as much as trade policy. Investments in recycling infrastructure, proper storage facilities, enforcement of environmental regulations, and technical assistance for developing countries are all critical components of a long-term solution.

Broader Implications for Plastic Pollution

This research adds weight to ongoing debates about environmental justice, global recycling systems, and the limits of exporting waste as a solution. Sending plastic abroad may reduce visible waste in exporting countries, but it often shifts the environmental burden elsewhere.

The findings also raise questions about how recycling is measured and marketed. When plastic intended for recycling ends up as coastal litter, the environmental benefits are lost, and the pollution becomes harder to control.

Looking Ahead

As plastic production continues to rise worldwide, understanding the real consequences of waste trade becomes increasingly important. This study provides rare, large-scale empirical evidence that plastic waste imports are not just an economic transaction but an environmental risk.

Addressing coastal plastic pollution will require coordinated international policy, stronger waste management systems, and reduced plastic production overall. Without these steps, the global plastic waste trade is likely to remain a significant contributor to coastal litter for years to come.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2025.108848