Greenland Was Ice-Free 400,000 Years Ago And A New Documentary Shows How Scientists Figured It Out

For most of us, Greenland is almost synonymous with ice. Today, the Greenland Ice Sheet blankets nearly the entire island, holding enough frozen water to raise global sea levels by several meters if it were to melt completely. But new research, highlighted in a recently released documentary, shows that Greenland has not always looked the way it does now. In fact, around 400,000 years ago, large parts of Greenland that are currently buried under thick ice were exposed to air, sunlight, soil, and even plant life.

This remarkable finding is the focus of the documentary The Memory of Darkness, Light and Ice, which follows scientists as they piece together evidence from forgotten ice and sediment samples collected decades ago. The work does not just rewrite part of Greenland’s history—it also offers important clues about Earth’s future in a warming world.

Understanding Greenland’s Past Through Forgotten Samples

The scientific story behind the documentary begins in an unexpected place: the Cold War. In 1959, the United States built a secret military base known as Camp Century beneath the Greenland Ice Sheet, roughly 150 miles inland. While the base had military objectives, scientists working there also carried out ambitious research projects. One of the most significant involved drilling deep into the ice.

Before Camp Century was abandoned in 1967, researchers drilled more than 1,000 meters through the ice sheet, reaching the sediment and soil beneath it. These samples were carefully stored but eventually faded into obscurity as scientific priorities shifted and technology lagged behind what was needed to fully analyze them.

Fast forward to 2019. An international team of scientists, led by researchers including Paul Bierman from the University of Vermont, began revisiting these long-forgotten samples. With modern analytical tools now available, the team realized the sediments held valuable information about Greenland’s ancient climate—information that could not be obtained easily today due to the immense cost and difficulty of drilling through ice.

What the Sediments Revealed About an Ice-Free Greenland

The sediment beneath the ice told a surprising story. Analysis showed that around 400,000 years ago, parts of Greenland—particularly in the northwest—were ice-free for an extended period. This conclusion came from multiple lines of evidence, including chemical signatures, soil characteristics, and traces of ancient ecosystems.

One of the key scientists involved, Eric Steig from the University of Washington, contributed isotope analysis to the project. His lab examined different versions, or isotopes, of elements such as oxygen, hydrogen, carbon, and nitrogen trapped in tiny pockets of water within the sediment. These isotopic ratios act like natural thermometers and ecological markers, revealing past temperatures and environmental conditions.

The results showed that Greenland experienced a prolonged warm period. Importantly, this warmth may not have been dramatically hotter than today’s climate—but it lasted long enough to significantly reduce the ice sheet. This challenges the idea that only extreme heat can destabilize Greenland’s ice and highlights the importance of duration as well as temperature.

Why Scientists Cannot Easily Repeat This Research Today

One obvious question is why scientists do not simply drill new holes through the ice to gather more samples. The answer is largely practical. Ice-core drilling is expensive, slow, and technically challenging, especially when the goal is to reach sediment and bedrock beneath kilometers of ice. Only a handful of such projects have ever succeeded.

In the 1960s, researchers already understood that water isotopes could preserve climate information, but they were not thinking about modern global warming. Ironically, this lack of foresight is what makes the Camp Century samples so valuable today. They provide a rare, direct look at what lies beneath the ice—something modern scientists would love to replicate on a larger scale but currently cannot.

Inside the Documentary The Memory of Darkness, Light and Ice

Directed by Kathy Kasic, a former evolutionary biologist turned filmmaker, the documentary captures the scientific process as it unfolds. Kasic followed researchers across laboratories in different countries, including visits to the University of Washington, documenting how old samples were reanalyzed and reinterpreted using modern techniques.

Rather than focusing on dramatic visuals alone, the film emphasizes how collaboration, patience, and new technology allowed scientists to unlock secrets that had been hidden for decades. The documentary debuted on major streaming platforms such as YouTube, Apple TV, and Amazon Prime, making this complex scientific story accessible to a broad audience.

The film also highlights a broader shift in climate science. For much of the 20th century, researchers focused on understanding ice ages and cold periods. Today, the urgent question has changed. Scientists are increasingly asking what Earth looked like during warmer periods with less ice, because that is the direction our climate is heading.

Why This Research Matters for the Future

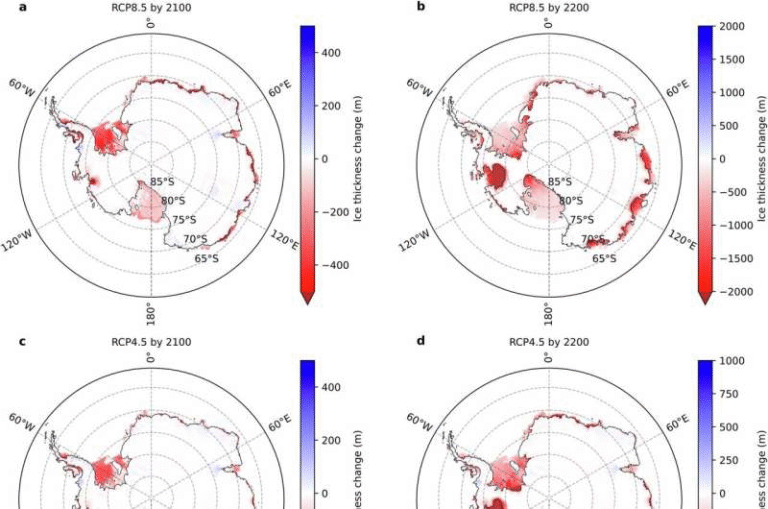

There is already strong evidence that the Greenland Ice Sheet is losing mass. Satellite observations show accelerating ice melt, and models predict continued retreat under current warming trends. The new findings from the Camp Century sediments strengthen the case that Greenland’s ice is not as stable as once believed.

If Greenland was able to lose significant ice in the past under conditions that were not dramatically warmer than today, it suggests that long-term warming could eventually lead to substantial ice loss again. This has serious implications for sea-level rise, which threatens coastal communities around the world.

By providing real-world evidence from the past, this research helps scientists refine ice-sheet models used to predict future changes. Better models mean more accurate projections, which are critical for planning and adaptation.

Extra Context How Ice Sheets Record Earth’s Climate

Ice sheets and the sediments beneath them act as natural archives of Earth’s history. Ice layers trap air bubbles, dust, and chemical signatures that reflect atmospheric conditions at the time they formed. Sediments, on the other hand, can preserve evidence of soil development, plant growth, and microbial activity.

Together, these records allow scientists to reconstruct past climates with surprising detail. Greenland, Antarctica, and other polar regions are especially important because changes there have global consequences, particularly for sea levels.

What Makes the Camp Century Discovery Unique

What sets this research apart is the combination of historic samples and modern science. The Camp Century sediments were collected at a time when no one imagined they would be used to study future climate risks. Today, they offer one of the clearest pieces of evidence that Greenland’s ice sheet has vanished, at least partially, in the geological past.

This discovery also underscores the value of preserving scientific samples. What may seem unimportant or incomplete at one point in time can become invaluable decades later, as new questions and technologies emerge.

Research Reference

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06758-3