Hidden Chemistry of Iron Minerals Reveals How Soils Lock Away Massive Amounts of Carbon

Scientists have known for decades that soils play a huge role in storing carbon and keeping it out of the atmosphere. What has remained unclear is how this storage works at a molecular level—especially the role played by iron minerals that are widespread in soils across the planet. A new study from Northwestern University now provides the most detailed explanation yet, showing that iron oxide minerals use surprisingly diverse chemical strategies to trap carbon and keep it locked away for decades or even centuries.

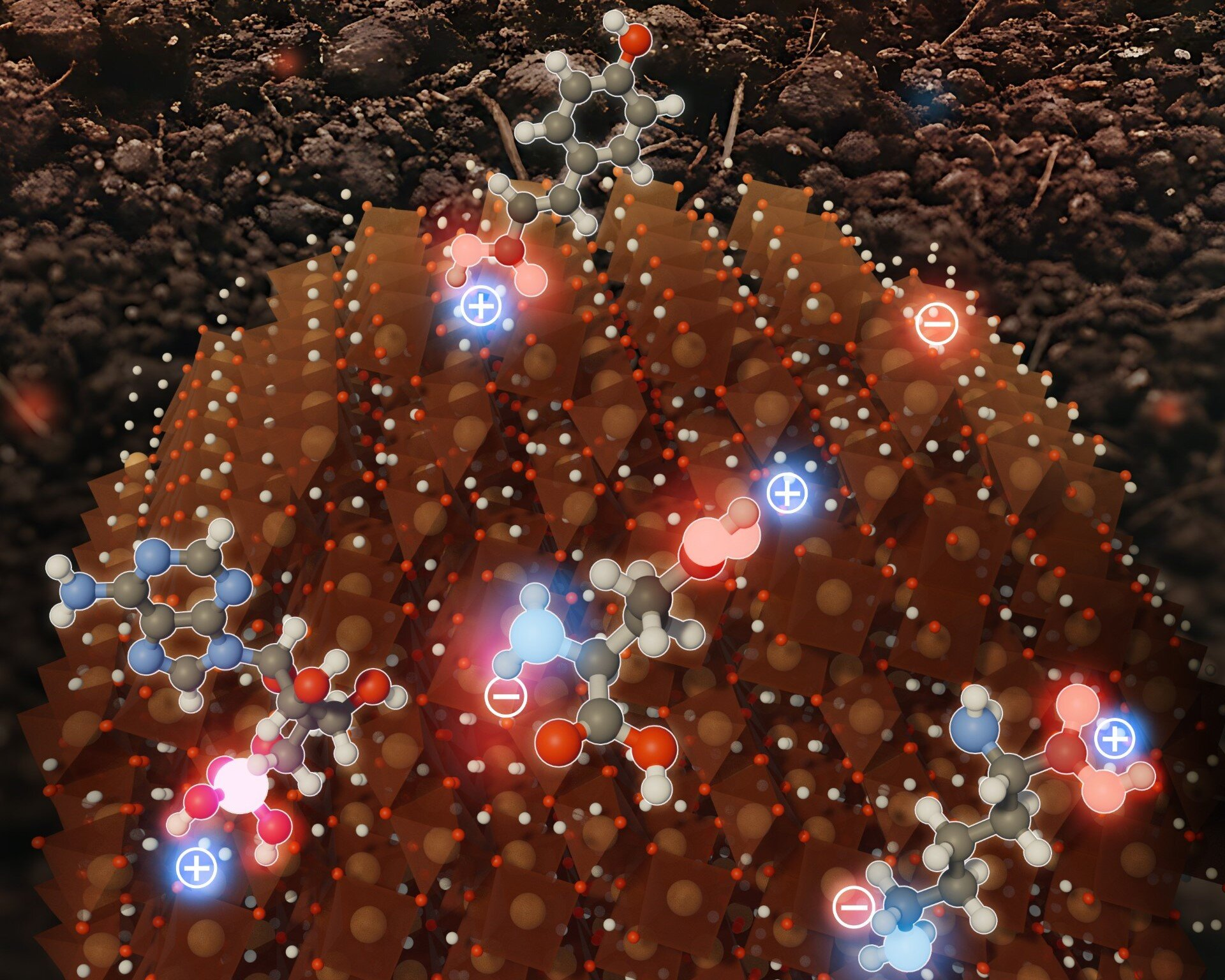

At the center of this research is ferrihydrite, a common iron oxide mineral found in soils rich in organic matter, particularly near plant roots and in sediments. Although ferrihydrite has long been recognized as a powerful carbon-storing mineral, the new study reveals that its effectiveness comes from a much more complex surface chemistry than scientists previously understood.

Why Soil Carbon Storage Matters So Much

Soil is one of Earth’s largest carbon reservoirs, holding an estimated 2,500 billion tons of carbon, second only to the oceans. This stored carbon is removed from the active carbon cycle, meaning it does not immediately return to the atmosphere as carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases. Understanding how soil locks away carbon is critical for improving climate models, predicting long-term carbon stability, and developing better land and soil management strategies.

Iron oxide minerals are especially important in this process. Researchers estimate that more than one-third of the organic carbon stored in soils is associated with iron oxides. Yet until now, scientists lacked a clear, quantitative explanation of how these minerals interact with such a wide variety of organic compounds.

Ferrihydrite Is Not as Simple as It Looks

Ferrihydrite is typically described as having an overall positive electrical charge under many environmental conditions. This led to a long-standing assumption that it primarily attracts and binds negatively charged organic molecules through simple electrostatic attraction. However, real-world observations showed something didn’t add up—ferrihydrite was also binding positively charged and even neutral organic compounds.

The new study resolves this puzzle by revealing that ferrihydrite’s surface is far from uniform. Instead of being evenly charged, the surface forms a nanoscale mosaic of positive and negative charge patches. These intermixed regions allow the mineral to interact with a much broader range of molecules than previously assumed.

This discovery explains why ferrihydrite can simultaneously attract negatively charged species like phosphate, positively charged metal ions, and a wide array of organic compounds with different chemical properties.

Multiple Ways of Binding Carbon, Not Just One

Another major finding of the study is that ferrihydrite does not rely on a single chemical mechanism to trap organic matter. Instead, it uses multiple binding strategies, each with different strengths and long-term implications for carbon storage.

Using a combination of high-resolution molecular modeling, atomic force microscopy, and infrared spectroscopy, the research team directly observed how different organic molecules attach to the mineral surface. The results showed clear patterns:

- Positively charged amino acids bind to negatively charged patches on ferrihydrite.

- Negatively charged amino acids attach to positively charged regions.

- Ribonucleotides—important biological molecules—are initially attracted by electrostatic forces and then form much stronger chemical bonds with iron atoms on the surface.

- Sugars, which tend to be neutral, bind through hydrogen bonding, creating weaker but still meaningful associations.

This combination of electrostatic attraction, chemical bonding, and hydrogen bonding makes ferrihydrite a highly versatile carbon trap, capable of holding onto organic matter with very different structures and chemical behaviors.

Why Some Carbon Stays Locked Away Longer Than Others

One of the most important implications of these findings is that not all organic carbon is stored equally. Molecules that form strong chemical bonds with iron atoms are more likely to remain protected in soils over long timescales. In contrast, molecules that attach through weaker hydrogen bonds may be more vulnerable to microbial breakdown and eventual release as greenhouse gases.

This helps explain why certain types of organic matter persist in soils while others are quickly decomposed. The mineral surface essentially acts as a gatekeeper, determining which molecules are shielded from microbes and which remain accessible.

Iron Minerals and the Global Carbon Cycle

The fate of organic carbon in soils is tightly linked to the global carbon cycle. When organic matter is broken down by microbes, it can be transformed into carbon dioxide or methane, both of which contribute to climate warming. By stabilizing organic compounds on mineral surfaces, iron oxides like ferrihydrite slow this process dramatically.

This study provides the missing quantitative framework needed to better represent mineral–organic interactions in Earth system and climate models. Without this level of detail, long-term predictions about soil carbon stability remain uncertain.

A Closer Look at the Tools Behind the Discovery

The researchers combined laboratory experiments with advanced theoretical modeling to reach their conclusions. Atomic force microscopy allowed them to visualize charge distributions on the mineral surface at extremely fine scales. Infrared spectroscopy helped identify exactly how different molecules bonded to ferrihydrite, while molecular simulations connected these observations to fundamental chemical principles.

Together, these methods produced the most detailed picture to date of ferrihydrite’s surface chemistry, moving beyond simplified assumptions that have guided soil science for decades.

What This Means for Soil Management and Climate Research

Understanding how iron minerals trap carbon has practical implications beyond basic science. Soil management practices that preserve or enhance iron oxide content could help improve long-term carbon sequestration. This is especially relevant in agricultural systems, wetlands, and restoration projects aimed at reducing atmospheric carbon levels.

The findings also raise new questions. Once organic molecules attach to mineral surfaces, what happens next? Some may undergo chemical transformations that make them even more stable, while others could become available for slow degradation. Exploring these post-binding processes is the next step for the research team.

Expanding Our Understanding of Soil as a Living System

Soils are often treated as passive storage spaces, but studies like this highlight how dynamic and chemically active they really are. Minerals, microbes, and organic compounds interact in complex ways that determine the long-term fate of carbon on Earth.

Iron minerals, once thought to be simple electrostatic attractors, now emerge as chemically sophisticated players in climate regulation. By revealing the hidden chemistry behind their carbon-trapping abilities, this research adds an important piece to the puzzle of how our planet naturally manages carbon—and how that system might respond to environmental change.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5c10850