Hourly Weather Records Reveal Significant Shifts in Freeze and Heat-Stress Patterns Across the United States

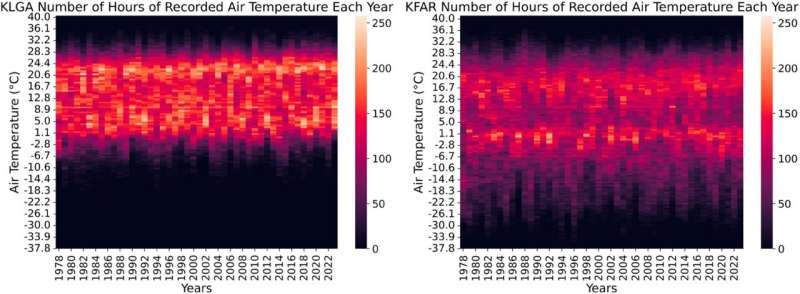

A new climate study using nearly five decades of hourly weather data has revealed clear and measurable shifts in how long different parts of the United States spend in freezing and heat-stress conditions each year. Researchers from North Carolina State University analyzed temperature records from 340 weather stations across the contiguous U.S. and southern Canada, using data from 1978 through 2023. Their goal was simple but powerful: instead of looking at temperature averages or isolated hot/cold days, they focused on how many hours each location spent below 32°F (0°C) or above 86°F (30°C). These thresholds matter because they directly affect agriculture, ecosystems, energy usage, buildings, and everyday life.

Their findings show two clear and significant trends. First, large portions of the northeastern United States are experiencing far fewer freezing hours than they did in the late 1970s—equivalent to a loss of about 1.5 to 2 weeks of below-freezing temperatures each year. Second, parts of the Gulf Coast, Southwest, and desert states have gained around 1.5 weeks of temperatures that exceed 86°F, a level known to cause heat stress in animals, crops, and people. The study highlights how small shifts in average temperatures can produce big changes in the number of hours spent above or below critical thresholds.

The research team, led by Sandra Yuter, explains that a few degrees of warming doesn’t always sound alarming on paper. But the meaning changes when a region that usually experiences 30°F now finds itself spending more time at 33°F. That subtle shift can alter plant cycles, freeze-thaw patterns, wildlife behavior, and winter conditions. Similarly, going from a short afternoon high of 90°F to long stretches where that heat lasts for five or six hours can dramatically increase stress on crops, livestock, and human health.

Using high-resolution hourly temperature data from the National Centers for Environmental Information’s Integrated Surface Database Lite, the researchers computed the number of hours each station spent beyond those key thresholds each year. They also examined decadal trends to smooth out short-term variability and highlight long-term patterns. Their approach provides a way to talk about climate change in a way that aligns directly with what people actually experience—number of cold mornings, length of hot afternoons, and duration of weather conditions that stress living systems.

The study’s most striking finding is the transformation in winter conditions in the northeastern U.S. Many areas east of the Mississippi River and north of the 37th parallel show consistent declines in freezing hours. This reduction of 1.5 to 2 weeks of freezing conditions affects winter recreation, pest populations, snowpack formation, and freeze-thaw cycles that influence road and building maintenance.

At the same time, certain parts of Arizona, New Mexico, southern Nevada, southern California, and southern Texas are experiencing notable increases in heat-stress hours. The threshold chosen for heat stress, 86°F, is based on well-documented impacts on agriculture and livestock physiology. The researchers note that the length of exposure matters greatly: experiencing 90°F for one hour is not the same as enduring it for six hours, even if the daily maximum temperature is identical.

Some regions showed no significant trend. The Midwest, for instance, displayed such high year-to-year temperature variability that clear long-term patterns were harder to detect. This variability does not mean the region isn’t experiencing climate change; rather, its natural swings make subtle trends more difficult to separate from background noise.

The study also connects these hourly temperature patterns to sector-specific impacts. For agriculture, fewer freezing hours can change which crops survive winter, alter pest pressures, and affect fruit-tree chill requirements. More heat-stress hours increase water demand, reduce yields, and create additional strain on livestock. For ecosystems, shifts in freeze and heat durations influence species ranges, migration timing, flowering cycles, and habitat conditions. For human systems, longer durations of heat drive up cooling energy demand, while fewer freezing hours reduce heating demand—changing the overall energy balance for homes and businesses.

The researchers emphasize that the United States is geographically huge, so these changes will differ dramatically by region. The study’s value lies in how it breaks these differences down so that local planners, policymakers, and homeowners can make informed decisions. Instead of relying on national averages, they can look at local hourly data to understand what’s really changing on the ground.

A key goal of the study is to offer climate information that resonates with everyday experience. People don’t necessarily notice that their region’s average annual temperature has increased by 2°F. But they do notice when winters feel shorter, when frost arrives later, or when summer afternoons seem to drag on with unrelenting heat. The authors argue that hourly temperature data—especially the number of hours at biologically or structurally important thresholds—can be a powerful way to translate climate trends into insights that communities can act on.

To support broader use, the team made the dataset and its analysis tools publicly available. Local governments can use them to evaluate cooling-center needs, energy planners can use them to assess HVAC demand shifts, and agricultural specialists can use them to forecast crop stress. The researchers also suggest that this method can help identify where climate impacts may show up first in ecosystems, such as changes in plant blooming or animal behavior.

The broader conversation around this study connects to a wider trend in climate science: the move toward high-resolution, threshold-based climate indicators. These indicators can reveal changes before extreme events occur. For example, even if a region isn’t experiencing more record-breaking heat waves, a steady increase in hours spent above moderate heat-stress levels can still produce cumulative impacts.

Another important point is that freezing thresholds are crucial not just for agriculture but also for infrastructure longevity. Freeze-thaw cycles cause cracking in pavement, stress in building materials, and changes in soil structure. A reduction in freezing hours could mean fewer freeze-thaw cycles in some areas, but it might also mean more unpredictable timing of those cycles—something that engineers and road-maintenance crews must adapt to.

Meanwhile, rising heat-stress hours have implications for public health. Extended periods of heat increase the risk of heat exhaustion and heatstroke, especially among elderly populations, outdoor workers, and people without adequate cooling. As the duration of these hot periods increases, public-health agencies may need to adjust emergency plans, cooling-center operations, and public-awareness campaigns.

While this study focuses solely on temperature, it opens a door to similar analyses using humidity, wind, precipitation, and soil moisture. Since many climate impacts depend on combinations of weather conditions, not just temperature alone, future research may build on this approach to give communities even clearer tools for climate adaptation.

Overall, the findings paint a picture of a country where climate change expresses itself not only through extreme events but through quiet, measurable shifts in how long we spend in temperatures that matter deeply to ecosystems, agriculture, and infrastructure. By looking at hours, not just averages, the study highlights the subtle but consequential ways the U.S. climate is evolving from season to season and decade to decade.

Research Paper:

https://journals.plos.org/climate/article?id=10.1371/journal.pclm.0000736