How Human-Caused Climate Change Is Driving Nearly Half of Harmful Wildfire Smoke in the Western US

Wildfires in the western United States have become more frequent, more intense, and far more damaging over the last three decades. While rising temperatures and prolonged droughts are often mentioned as contributing factors, a new study from Harvard University goes much further. It puts hard numbers on how much of today’s wildfire damage and smoke pollution can be directly traced to human-caused climate change. The results are striking: nearly half of the most dangerous wildfire smoke exposure in the western U.S. is now linked to warming driven by greenhouse gas emissions.

This research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, represents one of the most detailed efforts yet to separate natural wildfire behavior from the influence of climate change.

Understanding What the Study Set Out to Measure

For years, scientists have known that warmer temperatures dry out vegetation and create ideal conditions for wildfires. What has been harder to determine is how much of the increase in wildfire activity and smoke pollution would not have happened without climate change.

Researchers from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) tackled this problem by focusing on the western United States, where wildfire activity has surged since the early 1990s. Their goal was to quantify the share of burned land, fire emissions, and smoke-related air pollution that can be directly attributed to human-driven warming, rather than natural climate variability.

To do this, the team combined decades of observations with machine learning, large-scale climate models, and atmospheric chemistry simulations. This multi-layered approach allowed them to isolate the fingerprint of climate change on wildfire behavior and smoke exposure.

How Much Wildfire Damage Is Due to Climate Change

One of the most important findings of the study is how strongly climate change has influenced the total area burned by wildfires.

Across western U.S. forests, climate change accounted for 60 to 82 percent of the total burned area since the early 1990s. In central and southern California, where wildfires are influenced by both forest and chaparral ecosystems, climate change still explained about 33 percent of burned land.

When the researchers looked at emissions from fires across the entire United States, they found that climate change was responsible for an average of 65 percent of total fire emissions between 1997 and 2020. These emissions include gases and particles released when vegetation burns, many of which directly affect air quality and human health.

This means that a large share of today’s wildfire impacts are not just the result of natural cycles or land-use practices alone, but are tightly linked to long-term warming trends caused by human activity.

The Link Between Climate Change and Dangerous Smoke

Wildfires are not just destructive because they burn land. They also release massive amounts of fine particulate matter, known as PM2.5, which poses serious health risks.

PM2.5 particles are extremely small and can travel deep into the lungs and even enter the bloodstream. Exposure has been linked to respiratory illnesses, heart disease, strokes, and premature death.

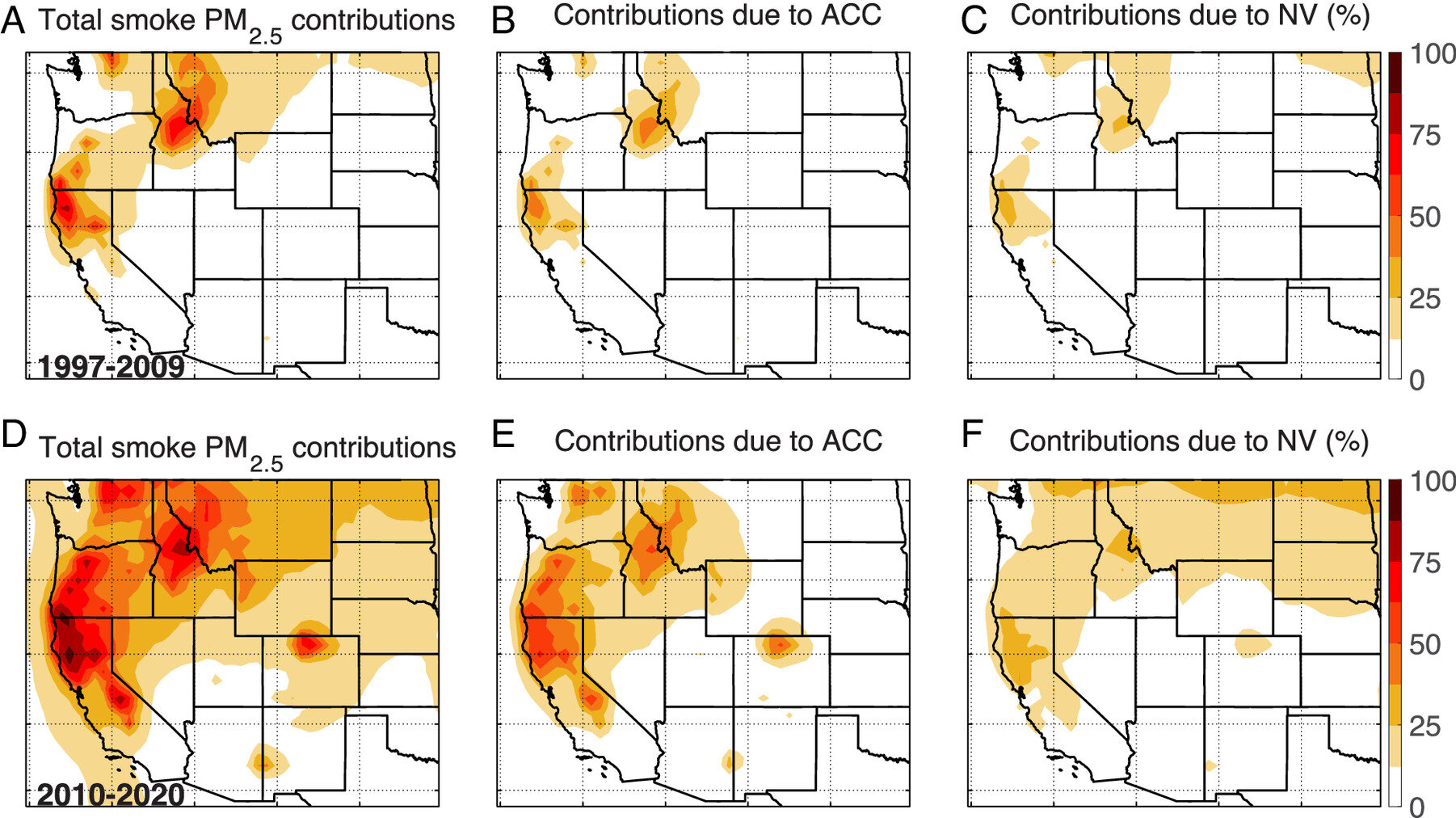

According to the study, from 1997 to 2020, nearly half of wildfire-related PM2.5 exposure in the western United States can be traced directly to climate change. Looking more closely at the most recent decade, from 2010 to 2020, climate change explained 58 percent of the increase in this harmful smoke pollution.

In practical terms, this means that rising temperatures and drier conditions have significantly amplified how much toxic smoke people are breathing during wildfire seasons.

Regions Facing the Worst Smoke Exposure

The study also breaks down where climate-driven smoke has hit the hardest.

Areas including northern California and parts of Oregon, Washington, and Idaho experienced particularly severe impacts. In these regions, climate-driven wildfire smoke accounted for 44 to 66 percent of total PM2.5 pollution between 2010 and 2020.

For residents living in these areas during that decade, the findings suggest that at least half of the fine particulate matter they inhaled came from wildfire smoke, much of it intensified by climate change.

This highlights that wildfire smoke is no longer a short-term nuisance or a localized issue. It has become a dominant source of air pollution across large parts of the western U.S.

How the Researchers Reached Their Conclusions

To reach these conclusions, the Harvard team used a combination of advanced techniques.

They first divided the western U.S. into distinct ecosystems, including northwestern forested mountains, Mediterranean-type California regions, and cold interior deserts. For each ecosystem, they compiled decades of data on weather patterns, vegetation density, dryness, and burned areas.

Machine learning models were then used to understand how changes in temperature, humidity, and vegetation aridity influenced wildfire activity over time. By comparing real-world observations with modeled scenarios that excluded human-caused warming, the researchers were able to estimate what wildfire behavior would have looked like without climate change.

To translate wildfire activity into smoke exposure, the team relied on GEOS-Chem, a widely used chemical transport model that simulates how pollutants move through the atmosphere. This allowed them to estimate how much PM2.5 in the air was directly attributable to climate-driven fires.

Wildfire Smoke vs Other Sources of Air Pollution

One of the more revealing comparisons in the study involves other sources of air pollution.

Between 1997 and 2020, pollution from non-wildfire sources, such as factories, vehicles, and power plants, declined by about 44 percent across the United States. This reflects the success of air quality regulations, including the Clean Air Act.

Wildfire smoke, however, has followed the opposite trajectory. While industrial and transportation emissions have fallen, smoke from wildfires has increased steadily, erasing many of the gains made through decades of pollution control.

In some regions, wildfire smoke has now become the leading contributor to unhealthy air quality days.

The Role of Fire Suppression and Forest Management

The study also points to another important factor: the legacy of 20th-century fire suppression.

For decades, many wildfires were aggressively extinguished, allowing forests to grow denser and underbrush to accumulate. This buildup of fuel has likely made modern fires more intense when they do occur.

Researchers are now working to quantify how much this history of suppression has interacted with climate change to amplify wildfire behavior. While climate change sets the stage by drying out landscapes, excess fuel can worsen fire severity and smoke production.

Why Prescribed Burning Matters

One of the clearest implications of the research is the importance of prescribed burning and other proactive land management strategies.

Prescribed burns intentionally clear underbrush and reduce fuel loads under controlled conditions. While they do produce some smoke, they can significantly reduce the risk of catastrophic wildfires that generate massive and prolonged smoke exposure.

The findings suggest that managing forests more actively, alongside efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, will be critical to limiting future wildfire smoke impacts.

A Broader Lesson About Climate and Health

This study underscores a larger reality: climate change is not a distant or abstract problem. It is already shaping the air people breathe, especially in fire-prone regions.

By showing that nearly half of harmful wildfire smoke exposure in the western U.S. is linked to human-caused warming, the research provides a clearer picture of how climate change translates into everyday health risks.

As wildfire seasons continue to lengthen and intensify, understanding these connections becomes essential for public health planning, land management, and climate policy.

Research Paper Reference

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2421903122