Increased Deciduous Tree Dominance Can Significantly Reduce Wildfire Carbon Losses in Boreal Forests, New Study Finds

As climate change continues to intensify wildfires across the northern parts of the planet, scientists are paying closer attention to what this means for boreal forests, one of Earth’s most important carbon reservoirs. Stretching across Alaska, Canada, Scandinavia, and Russia, these forests store an enormous amount of carbon in trees and soils built up over thousands of years. The big question researchers are now asking is simple but crucial: will boreal forests continue to act as a carbon sink, or are they slowly turning into a major carbon source as wildfires grow more frequent and severe?

A new study published in Nature Climate Change offers an important piece of that puzzle. The research shows that boreal forests dominated by deciduous trees—such as birch and aspen—release far less carbon during wildfires than forests dominated by coniferous trees, particularly black spruce. This shift in forest composition, already happening in many burned regions, could meaningfully reduce the amount of carbon released into the atmosphere during future fires.

Why Boreal Forests Matter So Much for the Climate

Boreal forests store a disproportionately large share of the world’s terrestrial carbon, much of it locked away in thick organic soils beneath the forest floor. For centuries, these ecosystems have acted as a stabilizing force in the global carbon cycle. However, rising temperatures in high-latitude regions have led to larger, hotter, and more frequent wildfires, threatening to undo that balance.

When boreal forests burn, carbon is released not only from trees but also from deep organic soil layers. If these emissions consistently exceed the carbon absorbed during regrowth, the region could shift from slowing climate change to accelerating it.

What the Study Looked At

The research was led by scientists from the Center for Ecosystem Science and Society (ECOSS) at Northern Arizona University. The lead author conducted the work as part of a master’s thesis, alongside senior researchers with long-standing expertise in boreal ecosystems.

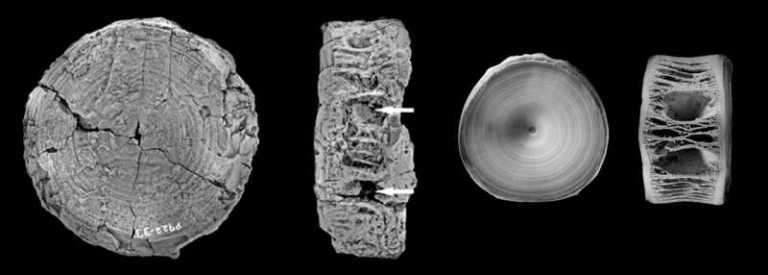

To understand how forest type influences carbon loss during wildfire, the team analyzed carbon pools and combustion losses across plots located within nearly a dozen large wildfire scars in Alaska and the Yukon. These sites represented a range of forest types, including black spruce–dominated conifer forests, deciduous forests, and mixed stands.

By directly measuring how much carbon was stored before fires and how much was lost during burning, the researchers were able to compare emissions across forest types under real-world fire conditions.

The Core Finding: Deciduous Forests Lose Far Less Carbon

The results were striking. Boreal forests dominated by deciduous species lost less than half as much carbon per unit area burned compared to black spruce forests. This pattern held true even during severe fire weather, when high temperatures and dry conditions typically drive extreme fire behavior.

The reason comes down to where carbon is stored. Deciduous forests tend to hold more of their carbon aboveground, particularly in thick, combustion-resistant tree stems. At the same time, they store less carbon in deep organic soils, which are highly flammable and responsible for some of the largest carbon losses during boreal fires.

In contrast, black spruce forests accumulate massive amounts of carbon in mosses and organic soil layers. When these layers burn, they release carbon that has been stored for centuries, leading to much higher emissions.

Different Forests, Different Fire Dynamics

Another important insight from the study is that what controls carbon loss differs by forest type. In conifer forests, carbon emissions were driven mainly by bottom-up factors such as fuel availability and soil moisture. Essentially, how much burnable material was present—and how dry it was—played the biggest role.

Deciduous and mixed forests behaved differently. In these forests, carbon loss was more strongly influenced by fire weather conditions, including temperature, wind, and atmospheric dryness. This finding surprised the researchers and suggests that while deciduous forests generally burn more cleanly, they may become more vulnerable under increasingly extreme fire weather driven by climate change.

A Potential Climate Feedback That Works in Our Favor

Across northwestern North America, severe wildfires are already pushing landscapes toward greater deciduous dominance. After intense fires, deciduous trees often regenerate more quickly than conifers, gradually reshaping forest composition.

The study suggests this shift could help slow the positive feedback loop between wildfire and climate warming. If future fires occur in forests that emit less carbon per burned area, overall wildfire-related emissions could be reduced—even if fire frequency continues to rise.

Importantly, the researchers did not claim this is a permanent solution. Fire weather is becoming more extreme, and forest succession can eventually shift back toward conifer dominance depending on conditions. Still, the findings highlight how vegetation change itself can influence climate outcomes.

Why This Research Is So Valuable

One of the biggest challenges in climate science is accurately representing wildfire emissions in carbon cycle and Earth system models. Many models assume relatively uniform behavior across boreal forests, which this study clearly shows is not the case.

By providing direct measurements of carbon loss across different forest types and identifying the mechanisms behind those losses, the research offers data that can significantly improve future climate projections.

Additional Context: Why Deciduous Trees Burn Differently

Deciduous trees generally have higher moisture content, less flammable foliage, and structural traits that reduce fire intensity. Their leaf litter also decomposes more quickly, preventing the buildup of thick, flammable organic layers.

Black spruce, on the other hand, is almost perfectly adapted to fire-prone environments. Its dense branches, resin-rich needles, and insulating moss layers promote intense fires that burn deep into the soil. While this helps the species regenerate, it comes at a major carbon cost.

What This Means Going Forward

This study does not suggest that wildfires are beneficial or that deciduous forests are immune to climate change. Instead, it shows that forest composition matters, sometimes in ways that can soften the climate impact of unavoidable disturbances.

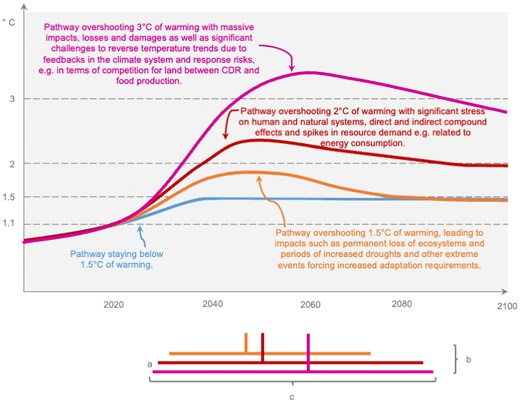

As warming continues, understanding how different ecosystems respond to fire—and how those responses feed back into the climate system—will be essential for making realistic predictions about Earth’s future.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/10.1038/s41558-025-02539-z