Invisible Groundwater Is Quietly Threatening Coastal Cities and Their Aging Infrastructure

Groundwater usually stays out of sight and out of mind, but scientists are warning that this hidden water could become one of the biggest challenges facing coastal cities in the coming decades. A new commentary published in Nature Cities lays out how groundwater rise, groundwater salinization, and combined human-driven and climate-driven changes underground are already creating risks for essential infrastructure that most people don’t even think about.

This new work comes from University of Rhode Island geoscientist Christopher Russoniello and his colleagues, who argue that many cities are overlooking these slow-moving but serious threats. Their goal is to push for much stronger monitoring and planning before problems become too difficult or too expensive to fix.

Understanding the Three Major Groundwater Hazards

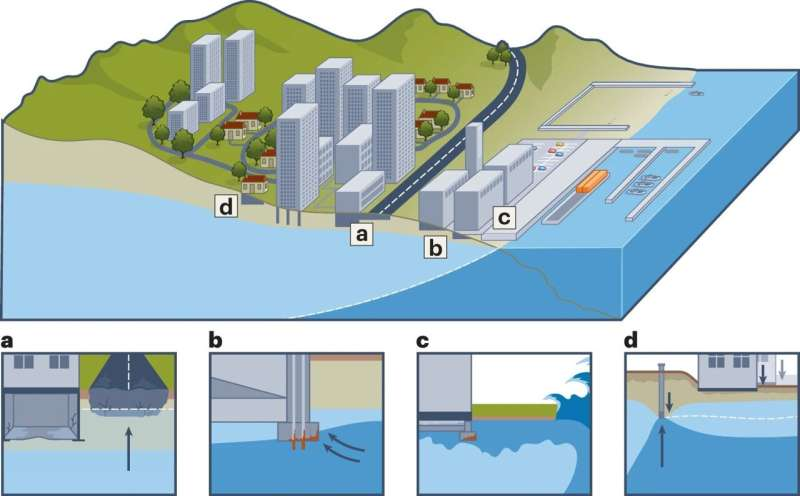

The authors highlight three specific groundwater hazards that coastal cities need to pay attention to. Each one affects urban infrastructure differently, but all three are closely tied to climate change and sea-level rise.

1. Groundwater Rise

As sea levels increase, the water table in nearby coastal zones rises as well. This upward movement can eventually reach underground structures, saturating soil that was never meant to stay wet. When the water table approaches the surface, it can:

- weaken roadbeds

- threaten building foundations

- flood basements

- disrupt subsurface electrical and telecom networks

- reduce the effectiveness of stormwater drainage systems

This isn’t the dramatic type of flooding people picture. It’s a slow, persistent change that undermines stability over years.

2. Groundwater Salinization

Saltwater intrusion is another major issue. As saltwater pushes inland underground, it increases the salinity of groundwater that urban infrastructure often interacts with. Saltwater corrodes pipes, metal components, and reinforced concrete far more quickly than freshwater.

This poses a risk to:

- buried metal pipes

- septic systems

- tanks

- concrete foundations and slabs

Higher salinity can also make groundwater unusable for drinking or irrigation, putting additional pressure on water supply systems.

3. Compound Man-Made and Climate-Related Groundwater Changes

Cities themselves often alter groundwater systems through pumping, drainage infrastructure, impermeable pavement, and underground construction. When these man-made changes combine with climate-driven groundwater rise, the effects can be unpredictable.

For example, a drainage system designed decades ago might not function when salty groundwater reaches new elevations. Underground cavities or backfill areas may become unstable. Wastewater systems can be overloaded if groundwater infiltrates sewer lines.

All of these factors together create a complex situation that requires detailed monitoring.

How This Threatens Urban Infrastructure

The vulnerable infrastructure includes nearly everything buried beneath coastal cities. According to the researchers, the most affected systems include:

- roads and pavements

- sewer networks

- septic systems

- buried gas lines

- electric lines

- building foundations

- underground storage tanks and pipes

Saltwater accelerates corrosion, making metal pipes and reinforced concrete particularly vulnerable. Rising groundwater can also infiltrate sewers, overwhelm drainage systems, and trigger more frequent surface flooding even without storms.

Russoniello emphasized that groundwater plays a bigger role in urban flooding than many previously believed. Earlier research tended to focus on rural or natural coastal areas, but this new work makes it clear that cities face an equally serious, often overlooked threat.

Why Many Cities Haven’t Noticed the Problem Yet

Coastal cities often focus on surface-level hazards—storm surge, sea-level rise, coastal erosion, and heavy rainfall. Groundwater, by contrast, moves upward quietly and gradually.

The team highlights Warren, Rhode Island as an example. The town does not rely on groundwater for its water supply and is more urbanized than other study sites in South Carolina and Delaware. This means groundwater issues have gone largely unnoticed, even though the subsurface changes could still pose risks.

Russoniello and fellow researchers, as part of a team led by URI professor Emi Uchida, are working under an NSF EPSCoR grant to study how flooding affects communities like Warren. Their group includes social scientists, groundwater specialists, and engineers who are collaborating to understand what communities need and how they can adapt.

The fact that Warren isn’t a groundwater-dependent community makes it a perfect example of how risks can remain invisible until something goes wrong—such as failing pipes, flooded basements, or damaged foundations.

Practical Solutions the Researchers Recommend

The commentary also offers several solutions that cities can consider adopting. These are particularly relevant for coastal communities planning infrastructure upgrades or new urban developments.

Engineering and Material Improvements

- Using corrosion-resistant pipes

- Reinforcing concrete structures in vulnerable zones

- Upgrading or redesigning drainage systems to handle groundwater rise

These changes can extend the lifespan of utilities and reduce maintenance costs.

Better Monitoring Systems

The team emphasizes the need for:

- geophysical surveys

- multilevel wells

- sensors that track electrical conductivity and water pressure

These tools help detect early warning signs of groundwater rise or salinity changes long before visible damage occurs.

Improved Planning and Codes

Cities may need to:

- update building codes

- redesign zoning regulations

- create groundwater-sensitive development guidelines

- integrate hydrogeology into coastal resilience planning

The researchers argue that new programs involving urban planning, social science, civil engineering, hydrogeology, materials science, and coastal science will be crucial for long-term success.

Additional Background: Why Groundwater Is Becoming a Bigger Issue Everywhere

Groundwater rise is linked directly to sea-level rise, which causes coastal aquifers to swell. Even a small increase in sea level can raise the water table far inland. Scientists have shown that:

- groundwater levels often rise faster than sea levels in certain areas

- buried infrastructure becomes vulnerable before neighborhoods see surface flooding

- low-lying coastal cities with heavy urban development are especially susceptible

More than two billion people live in coastal zones globally, meaning the issue is not isolated to the U.S. Many cities across Asia, Europe, and island nations may also face similar challenges.

In addition, urban development often reduces the capacity of the ground to absorb and move water naturally. Impermeable surfaces like asphalt and concrete restrict infiltration, which can worsen subsurface flooding.

These combined pressures make groundwater dynamics a major piece of the climate adaptation puzzle.

Why This Research Matters for Long-Term Climate Planning

Addressing groundwater threats isn’t just about preventing floods. It’s about protecting:

- drinking water supplies

- wastewater infrastructure

- transportation systems

- electrical and communication networks

- building safety

- environmental health

If cities ignore groundwater, repairs and retrofits later could cost billions. Early research like this ensures that governments and planners have the information they need to make proactive decisions.

The authors of the Nature Cities commentary hope their work encourages leaders to take groundwater seriously and to integrate it into broader climate-resilience strategies.

Research Reference

Invisible Groundwater Threats to Coastal Urban Infrastructure

https://www.nature.com/articles/s44284-025-00298-8