Kansas Researchers Launch a Near-Real-Time Flood Mapping Dashboard for Statewide Emergency Response

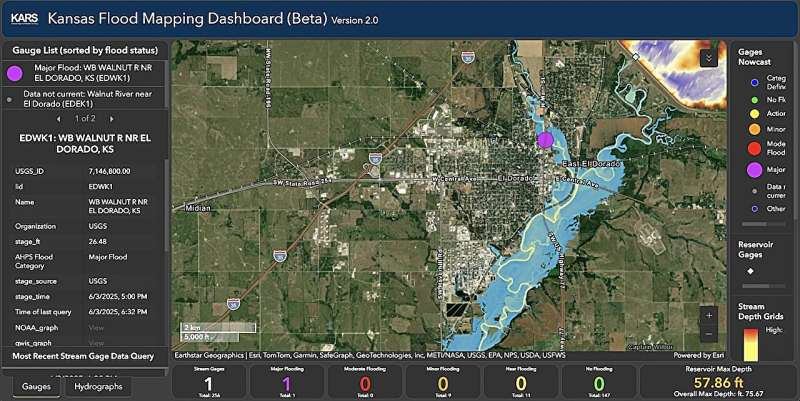

The University of Kansas has introduced a new Kansas Flood Mapping Dashboard, a digital tool built to give emergency managers and the public a clearer picture of flooding as it happens. This web-based system automatically maps both flood extent and flood depth across major waterways in Kansas, updating every two hours. It represents years of research led by experts at the Kansas Biological Survey & Center for Ecological Research, particularly within the Kansas Applied Remote Sensing (KARS) program.

The dashboard was created to address a major need for reliable, fast, and accessible flood information. Flooding has always been a serious concern in central and eastern Kansas, and major events such as the 2019 floods highlighted gaps in statewide situational awareness. The new mapping system fills this gap by pulling together large volumes of real-time data and applying advanced modeling to produce easy-to-read flood visualizations.

The dashboard uses stream gauge data from the National Weather Service and the U.S. Geological Survey, among other sources. This information is then fed into the terrain-based FLDPLN model (pronounced “floodplain”), a hydrologic model developed in 2008 at KU. FLDPLN uses elevation data and hydrologic flow principles to determine where water would naturally move during a flooding event. When combined with up-to-the-minute stream gauge readings, it generates detailed flood inundation maps that show which areas are underwater and how deeply they’re flooded.

This modeling system did not appear overnight. Researchers began building the dashboard after the devastating 2019 Kansas floods. Since then, it has been expanded, refined, and stress-tested during severe weather events. Earlier this year, the Kansas Division of Emergency Management praised the dashboard for its responsiveness and accuracy during intense spring flooding, reinforcing its value as an operational tool.

The dashboard was designed not only for disaster response centers but also for everyday Kansans who want to stay informed. Users can get a quick overview of current flood conditions, check the depth of water along key rivers, and anticipate potential impacts in their communities. It aims to support public safety, planning, and outreach, especially as extreme rainfall events become more common.

Behind the scenes, this project is the result of collaboration across multiple institutions. Research professor Jude Kastens, who leads the KARS program, guided the development of the system from the beginning. His background growing up in rural northwest Kansas shaped his long-term interest in weather, flooding, and applied geography. Although his home region does not flood as often as eastern Kansas, the dramatic impact of heavy rainfall helped spark his career in environmental modeling.

Many others contributed to the tool’s development. David Weiss, a KARS researcher and Ph.D. student, is the lead architect of the current version of the dashboard. Xingong Li, a professor in the KU Department of Geography & Atmospheric Science, played a foundational role by helping develop real-time mapping capabilities. Over the years, several graduate students and collaborating researchers have also supported the modeling, coding, map production, and testing phases of the project.

The dashboard is part of a broader effort by KARS to help Kansas agencies manage land and water resources. KARS works closely with state organizations such as the Kansas Water Office and the Kansas Department of Agriculture, offering research and tools that improve environmental decision-making. The flood mapping system aligns closely with this mission by providing a resource that’s useful both in routine monitoring and during emergencies.

In addition to operational tools, KU researchers have continued to advance scientific understanding of flood mapping. A recent paper published in the journal Remote Sensing highlights a new approach called FLDSensing. This method combines the existing FLDPLN model with satellite-derived flood boundary data to estimate water extent and depth. Rather than relying solely on traditional stream gauges, FLDSensing treats the visible shoreline of a flood—detected through satellite imagery—as a proxy gauge. This makes it possible to produce accurate flood maps in areas where no physical gauges exist.

The FLDSensing research was led by Jackson Edwards, who completed the work as part of his master’s research at KU. Co-authors included KU researchers David Weiss and Xingong Li; University of Alabama researchers Francisco Gomez, Hamid Moradkhani, and Sagy Cohen; and University of Virginia researchers Son Kim Do and Venkataraman Lakshmi. Their findings demonstrate that this hybrid technique can provide reliable flood inundation estimates across large areas, expanding the usefulness of modeling tools like FLDPLN.

The KU team emphasizes that the dashboard is a team effort, and they expect to keep improving it. One major goal is to extend coverage into the western third of Kansas, where mapping is currently more limited. Another priority is to add features showing roadway impacts, which will make the dashboard even more practical for planning and emergency response. With each enhancement, the system will become a more comprehensive tool for both local authorities and residents.

Flood science itself is a growing field, and understanding how systems like this work can offer valuable insight. Flood modeling generally relies on three elements: terrain data, water level information, and hydrologic behavior. High-resolution elevation maps (often derived from LiDAR) help determine where water can flow or accumulate. Water level readings, whether from gauges or remote sensing, provide the real-time input. Models like FLDPLN blend these elements to simulate the spread of floods without requiring computationally heavy hydraulic simulations. This type of modeling is increasingly important because climate change is causing more frequent extreme rainfall events in the Midwest and around the world.

Remote sensing is also reshaping modern flood analysis. Satellite imagery can detect water boundaries even in areas with limited monitoring infrastructure. When paired with terrain-based models—like in the FLDSensing approach—it creates a powerful toolset that can scale across large geographic regions. This is particularly useful for rural or remote locations where deploying physical sensors is not practical.

Kansas serves as a strong example of how universities and state agencies can collaborate to improve public safety. By combining longstanding research expertise with modern data and technology, the state now has a resource that helps communities stay informed during critical weather events. The Kansas Flood Mapping Dashboard shows how applied research can translate into real-world benefits, especially when natural disasters demand rapid and reliable information.

As the dashboard continues to evolve, Kansas residents and emergency responders can expect even better tools for understanding and preparing for floods. With ongoing research, expanded coverage, and new features in development, this system is set to play a key role in the state’s flood management strategies for years to come.

Research Paper:

FLDSensing: Remote Sensing Flood Inundation Mapping with FLDPLN (2025)

https://www.mdpi.com/2072-4292/17/19/3362