Major Gaps in Global Satellite Forest Maps Are Raising Serious Policy Concerns Worldwide

For decades, governments, scientists, and international organizations have leaned heavily on satellite-derived forest maps as a foundational tool for fighting climate change, protecting biodiversity, and guiding development policy. These digital maps are often treated as authoritative answers to a deceptively simple question: where are the world’s forests? A new study, however, suggests that this confidence may be misplaced. According to recent research, many of the most widely used global forest maps disagree with each other to an alarming degree, creating significant uncertainty that could ripple through climate finance, conservation planning, and human development efforts.

The study, led by researchers from the University of Notre Dame and published in the journal One Earth, examined eight of the most commonly used global forest datasets. These datasets underpin everything from estimates of carbon storage to decisions about where conservation funding is allocated. When the researchers compared them, they found something striking: the datasets agreed on the location of forests only 26% of the time. In other words, nearly three-quarters of the global land area classified as forest by one dataset may be classified differently by another.

This level of disagreement matters because forest maps are not just academic tools. They shape real-world policies. Governments rely on them to report national forest cover under international climate agreements. Conservation groups use them to identify priority areas for protection. Development agencies use them to estimate how many people live near forests and depend on them for livelihoods. When the underlying data is inconsistent, the policies built on top of it become far more fragile.

Why Global Forest Maps Disagree So Widely

At the heart of the problem is a surprisingly basic issue: there is no single, universally accepted definition of a forest. Different datasets use different criteria to decide what qualifies. One map might label land as forest if as little as 10% of the area is covered by tree canopy, while another might require 50% or more canopy cover. Some datasets count scattered trees in savannas and grasslands as forests, while others exclude them entirely.

These definitional differences may sound minor, but at a global scale they translate into millions of hectares shifting back and forth between “forest” and “non-forest” depending on which map is consulted. The study found that these discrepancies can create uncertainty by a factor of ten in some estimates, particularly when it comes to forest area and carbon storage.

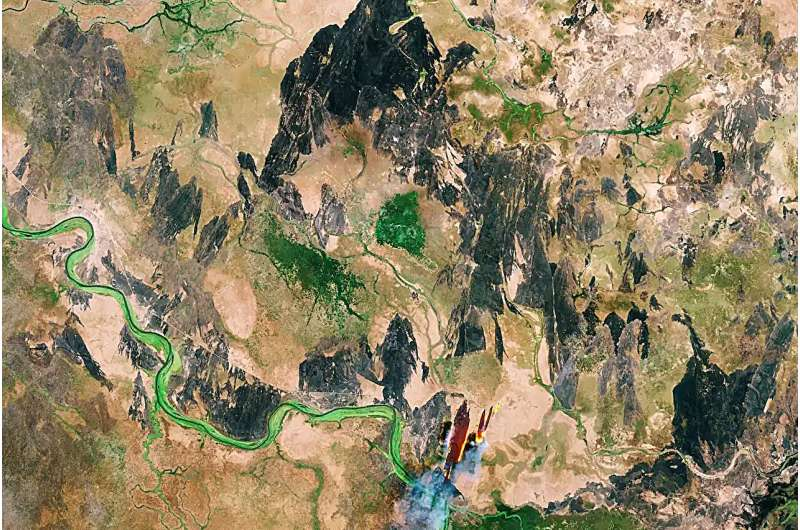

Technology also plays a role. Satellite sensors vary in resolution, meaning some can detect small patches of trees while others only pick up large, dense forest blocks. Algorithms used to classify land cover interpret satellite signals differently, especially in complex landscapes where forests blend into wetlands, shrublands, or agricultural mosaics. From space, a wooded savanna, a plantation, and a natural forest can sometimes look deceptively similar.

Real-World Consequences for People and Policy

To illustrate the stakes, the researchers examined case studies from Brazil, India, and Kenya. These examples show how the choice of dataset can dramatically change policy-relevant outcomes.

In India, for instance, the estimated number of people living in poverty near forests varied from 23 million to 252 million depending solely on which forest map was used. That range is not a rounding error; it is the difference between targeted social programs reaching a relatively small population or needing to support hundreds of millions of people. Similar uncertainties appeared in estimates of forest-dependent livelihoods and access to ecosystem services.

In Brazil, differences among forest maps affected assessments of habitat availability and carbon stocks, both of which are central to conservation planning and climate commitments. In Kenya, discrepancies influenced how much land was considered forested versus suitable for agriculture or grazing, with implications for land-use planning and conflict resolution.

These inconsistencies pose serious challenges for climate finance mechanisms, such as carbon markets and results-based payments for forest conservation. If countries overestimate their forest area, they may claim more carbon sequestration than actually exists. If they underestimate it, they may lose out on funding and protection opportunities. Either way, trust in global environmental markets can erode when baselines are unclear or contested.

Why Satellites Alone Are Not Enough

Satellite imagery has revolutionized environmental monitoring, but the study makes it clear that it is not a silver bullet. Viewing land from above provides incredible coverage, but it lacks local context. A patch of trees may be ecologically degraded, culturally important, intensively managed, or naturally regenerating, and satellites alone cannot always capture those distinctions.

The researchers argue that relying exclusively on remote sensing risks oversimplifying complex landscapes. This is particularly true in regions with dry forests, savannas, and mixed land-use systems, where tree cover does not neatly align with conventional ideas of forest.

A Framework to Navigate the “Digital Wilderness”

Rather than calling for a single “perfect” forest map, the study proposes a more practical solution. The authors developed a decision-support flowchart designed to help policymakers, journalists, and practitioners choose the dataset that best fits their specific goal. For example, a dataset suitable for estimating global carbon stocks may not be appropriate for assessing community livelihoods or biodiversity conservation.

The study also emphasizes the need for hybrid approaches that combine satellite data with on-the-ground observations. Local forest inventories, community mapping efforts, and ecological field studies can provide critical context that satellites miss. Integrating these perspectives can produce more accurate and inclusive representations of forests.

Why Standardization and Transparency Matter

Another key takeaway from the research is the importance of clear documentation and transparency. Users of forest data often assume that maps labeled “global forest cover” are directly comparable, when in fact they may be based on very different assumptions. Making definitions, thresholds, and uncertainties explicit would allow users to interpret results more responsibly.

Standardization does not necessarily mean forcing everyone to use the same definition of forest. Instead, it means clearly stating what definition is being used and why. Without that clarity, comparisons across countries, time periods, or policy frameworks become unreliable.

Broader Context: Forests and the Climate System

Forests play a central role in the global carbon cycle, absorbing roughly a quarter of human-caused carbon dioxide emissions each year. They also support biodiversity, regulate water cycles, and provide livelihoods for hundreds of millions of people. Because of this, forests sit at the intersection of climate policy, conservation, and development.

Accurate forest data is essential not only for tracking deforestation but also for understanding forest degradation, regrowth, and management. As climate change alters ecosystems, the ability to monitor these dynamics will become even more important. The study’s findings suggest that improving forest mapping is not just a technical challenge but a governance one, requiring collaboration across disciplines and regions.

Looking Ahead

The message of the study is not that satellite forest maps are useless. On the contrary, they remain indispensable. But treating them as unquestionable truths is risky. Recognizing their limitations, understanding their assumptions, and combining them with local knowledge can lead to better-informed decisions that genuinely support both environmental protection and human well-being.

As climate goals become more ambitious and funding flows increase, the demand for reliable data will only grow. Addressing the gaps in global forest maps is therefore not a niche technical issue; it is a foundational step toward credible, effective climate and development policy.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2025.101558