More Eyes on the Skies Can Help Planes Reduce Climate-Warming Contrails

Aviation’s impact on the climate is often discussed in terms of fuel burn and carbon dioxide emissions, but there is another major contributor that gets far less public attention: contrails. These are the long, thin cloud-like streaks that form behind aircraft as they cruise at high altitudes. A new study led by researchers at MIT shows that understanding and reducing the climate impact of contrails may depend on how well we observe them — and right now, we are missing a surprisingly large portion of the picture.

Contrails form when hot exhaust gases from aircraft engines mix with cold, humid air in the upper atmosphere. Tiny particles in the exhaust act as seeds, allowing water vapor to freeze into ice crystals. What begins as a narrow line can spread out over time, sometimes lasting for hours and covering large regions of the sky. When persistent, these contrails behave much like thin ice clouds, interacting with radiation in ways that can warm the planet.

While the exact scale of contrails’ climate impact is still uncertain, multiple studies suggest that contrails may be responsible for around half of aviation’s total climate effect. This makes them just as important — if not more so in the near term — than carbon dioxide emissions from aircraft.

One proposed solution is contrail avoidance. Pilots could slightly adjust their flight altitude to avoid atmospheric layers where contrails are most likely to form, much like they already do to avoid turbulence. However, this approach depends on one crucial factor: knowing where and when contrails will form. That is where observation and monitoring become essential.

How Satellites Are Used to Track Contrails

Scientists rely heavily on satellite imagery to detect contrails and study how they evolve. For years, geostationary satellites have been the backbone of contrail observation. These satellites orbit Earth at about 36,000 kilometers above the surface and remain fixed over the same region, capturing images every few minutes, day and night. Their strength lies in their wide coverage and high observation frequency.

However, geostationary satellites have a major limitation: image resolution. Because they are so far from Earth, the images they capture are much less detailed than those taken by satellites orbiting closer to the planet.

This is where low-Earth-orbit (LEO) satellites come in. LEO satellites fly at much lower altitudes and can capture images with far greater detail. Instruments such as the Visible Infrared Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) can detect smaller and thinner contrails that might otherwise go unnoticed. The downside is that LEO satellites only capture images as they pass overhead, meaning they observe the same area far less frequently than geostationary satellites.

What the New Study Found

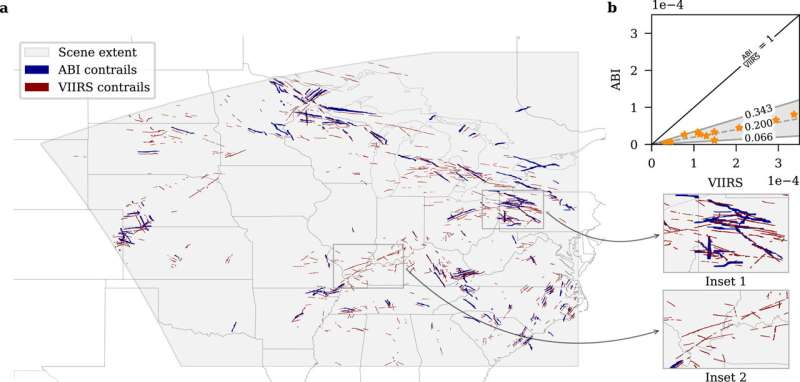

In this new study, MIT researchers set out to understand just how much contrail information might be missed when relying mainly on geostationary satellites. They compared imagery from the Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI) on geostationary satellites with higher-resolution imagery from VIIRS instruments aboard LEO satellites.

The research team analyzed images covering the contiguous United States for each month from December 2023 to November 2024. For every VIIRS image selected during a satellite flyby, they found corresponding ABI images taken at roughly the same time of day. All images were captured in the infrared spectrum and displayed in false color, making contrails visible both during the day and at night.

Instead of relying on automated detection alone, the researchers manually examined each image. They zoomed in, identified contrails by eye, and carefully outlined and labeled every contrail they could see.

The results were striking. The team found that geostationary satellite images missed about 80 percent of the contrails that were visible in the LEO satellite imagery. In other words, most contrails forming in the atmosphere were simply not being detected by the satellites most commonly used for contrail monitoring.

Why Smaller Contrails Still Matter

The contrails missed by geostationary satellites tend to be shorter, thinner, and younger. These fine threads often form immediately behind aircraft engines but are too small or faint to be clearly seen from geostationary orbit. Over time, some of these contrails grow larger and spread out, eventually becoming visible to geostationary imagers.

Importantly, the researchers note that missing 80 percent of contrails does not necessarily mean missing 80 percent of the climate impact. Larger, longer-lasting contrails — which geostationary satellites do capture — are generally thought to have a greater warming effect. Still, the sheer number of smaller contrails points to a major observational gap.

Relying on a single type of satellite creates an incomplete picture, especially as contrail avoidance strategies move closer to influencing airline operations and policy decisions.

The Case for a Multi-Observation Approach

The study strongly emphasizes the need for a multi-observational strategy. Each observation method has strengths and weaknesses:

- Geostationary satellites provide continuous, wide-area coverage and are excellent for tracking how contrails evolve over time.

- Low-Earth-orbit satellites offer higher resolution and can detect newly formed contrails that would otherwise be missed.

- Ground-based cameras and sensors could observe contrails in real time as they form, under the right conditions.

Ground-based observations are particularly valuable because they can be matched directly to specific aircraft and flight data. By linking a contrail to a particular plane, scientists can determine the exact altitude and atmospheric conditions where the contrail formed. Geostationary satellites can then be used to track that same contrail as it grows and spreads across the sky.

Over time, combining data from satellites and ground observations could help scientists understand the full life cycle of a contrail, from its initial formation to its eventual dissipation.

Why Contrails Warm the Planet

Contrails affect Earth’s energy balance in complex ways. During the daytime, they can both reflect incoming sunlight and trap outgoing heat. At night, when there is no sunlight to reflect, contrails primarily act as a heat-trapping blanket, warming the atmosphere below.

When averaged over time, studies show that the warming effect dominates, making contrails a net contributor to global warming. This is why reducing persistent contrails is considered one of the most promising near-term options for lowering aviation’s climate impact.

Toward Smarter Contrail Forecasting

With enough high-quality data, scientists aim to develop real-time forecasting models that can predict where contrails are likely to form and persist. Such models could allow pilots to make small altitude adjustments to avoid contrail-prone layers without significantly increasing fuel use.

Compared to other decarbonization strategies in aviation — such as sustainable fuels or new aircraft designs — contrail avoidance is seen as a relatively low-cost and fast-acting solution. However, researchers stress that it must be implemented carefully, based on accurate science and thorough verification.

Better tools, better observations, and a clearer understanding of contrail behavior are essential before large-scale deployment becomes practical.

Why This Research Matters

Aviation is one of the hardest sectors to decarbonize, and there are no easy fixes. This study highlights that improving how we observe the sky could unlock meaningful reductions in climate impact without waiting decades for new technologies.

By showing that current monitoring systems miss most contrails, the research makes a strong case for expanding observation methods and combining multiple data sources. More eyes on the sky could ultimately lead to smarter decisions in the air — and a smaller climate footprint on the ground.

Research paper:

Marlene V. Euchenhofer et al., Contrail Observation Limitations Using Geostationary Satellites, Geophysical Research Letters (2025).

https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GL118386