Nevada Cave Calcite Record Reveals 580,000 Years of Climate Shifts in the American Southwest

A remarkable calcite deposit discovered deep inside a southern Nevada cave has revealed 580,000 years of hydroclimate history, offering one of the longest and most complete terrestrial climate records ever found in an arid region. The research, led by scientists from Oregon State University (OSU) and recently published in Nature Communications, gives a clear picture of how the American Southwest has cycled between cool, wet glacial periods and hot, dry interglacial periods over half a million years — and what those patterns suggest about the region’s future.

How Scientists Accessed This Rare Climate Archive

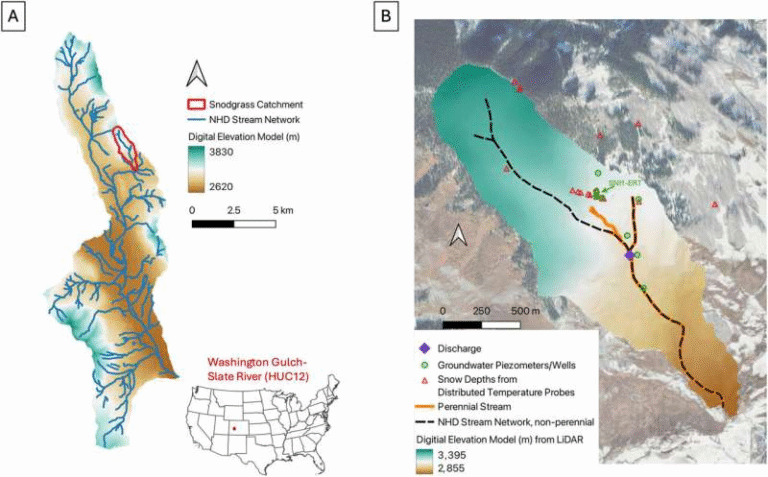

The discovery comes from a calcite formation inside Devils Hole II, part of a fissure-style cave system in southern Nevada. Unlike typical open caverns, Devils Hole is a narrow vertical crack in the Earth, partially flooded by groundwater that has been percolating through the region for hundreds of thousands of years.

To reach the calcite layer, OSU researchers descended roughly 20 meters down a narrow shaft, maneuvered through a tight opening, and accessed the deepest known chamber of the fissure. There, they drilled a one-meter-long core directly from the cave wall. This core contains layers of calcite deposited steadily over time — much like tree rings or ice cores — capturing the chemical fingerprints of ancient climate conditions.

The research team focused primarily on oxygen isotope ratios preserved in the calcite. These ratios are well-established climate indicators, revealing temperature changes, rainfall patterns, and shifts in groundwater availability at the time each calcite layer formed.

What the 580,000-Year Climate Record Shows

The calcite core captured data from the last six glacial–interglacial cycles, offering precise details on how the region’s hydroclimate transformed during each cycle.

During glacial periods, Nevada was cooler and significantly wetter, with higher groundwater levels and healthier vegetation. The region received more rainfall, largely because the Pacific storm track — a major source of winter precipitation — shifted farther south during these colder phases.

During interglacial periods, which are warmer phases like the one Earth is in today, the area became hotter and drier, leading to reduced groundwater recharge and less vegetation productivity.

One of the most striking findings is that midway through many interglacials, groundwater levels dropped sharply. This drop was followed by a notable decline in vegetation, indicating that heat combined with reduced rainfall creates a tipping point in the region’s water-vegetation balance.

Shifts in Storm Tracks and Their Consequences

The study also documented large swings in where Pacific rainstorms made landfall over tens of thousands of years. Today, most of the moisture-bearing winter storms hit the Pacific Northwest, but the research shows that during ice ages, these storms shifted dramatically southward — delivering much more rain to the Southwest.

This shifting storm belt directly influenced groundwater recharge. When storms favored the Southwest, aquifers filled and ecosystems thrived. When they shifted northward, the region experienced prolonged dryness and ecological stress.

These findings reveal that storm tracks can move quickly and dramatically, responding to global temperature changes. This sensitivity is an important clue for predicting future regional water patterns in the face of ongoing global warming.

A Rare Terrestrial Climate Archive

Most long-term climate records come from ice cores in Antarctica or Greenland, which don’t reflect land-based conditions in arid regions. Terrestrial records of similar length are extremely rare, especially in desert landscapes where organic material, sediment layers, and other climate markers are easily eroded or never formed.

The Devils Hole calcite deposit is therefore a unique and invaluable archive, providing a continuous, precisely dated, land-based climate record spanning more than half a million years. Its value extends beyond Nevada — it serves as a critical dataset for understanding arid-zone climate behavior worldwide.

What This Means for the Southwest’s Future

The southwestern United States is already experiencing declining groundwater, persistent drought, extreme summertime heat, and increasing water demand across states, cities, farms, and ecosystems.

This new paleo-record confirms that in past warm periods, the region naturally experienced low groundwater levels, reduced vegetation, and intense aridity — even without human influence.

With modern global warming intensifying these same pressures, the study raises concerns about the Southwest’s long-term livability, especially as temperatures rise and water resources continue to contract.

Understanding how temperature, water availability, and vegetation were tightly linked in the past helps scientists anticipate the thresholds the region might face in the coming decades and centuries.

About the Devils Hole Cave System

To appreciate the significance of this study, it helps to know what makes Devils Hole special:

- Devils Hole is part of the Ash Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, known for housing one of the world’s rarest fish — the Devils Hole pupfish, which survives in a nearby chamber connected to the same groundwater system.

- The cave system is a deep, water-filled fissure created by tectonic stretching of the Earth’s crust.

- Because the groundwater temperature stays stable and the mineral deposition occurs continuously, Devils Hole is one of the most stable and reliable climate recorders in the desert Southwest.

The site has long fascinated scientists because it combines extreme geology, biodiversity, and now one of the most detailed terrestrial climate histories ever documented.

Why Calcite Deposits Are Powerful Climate Tools

Calcite (a crystalline form of calcium carbonate) grows slowly and steadily in caves where mineral-rich groundwater evaporates or precipitates minerals onto cave walls. As it forms, it traps chemical signatures that reflect:

- Temperature at the time of deposition

- Rainfall sources and intensity

- Groundwater levels and flow patterns

- Large-scale atmospheric circulation shifts

These signatures remain stable for hundreds of thousands of years, creating some of the most reliable climate records available to scientists.

Because arid regions rarely preserve lakes, soils, or ice layers well, cave calcite deposits (known as speleothems) are especially valuable for reconstructing desert climates.

What Sets This Study Apart

Several factors make this new research a milestone:

- Length of record: 580,000 years is exceptionally long for any terrestrial climate archive.

- Precision: The oxygen isotope record is continuous and dated accurately across six glacial cycles.

- Location: Arid-zone data of this quality are extremely scarce.

- Insights into storm tracks: The clear evidence of shifting Pacific storm belts helps refine continental-scale climate models.

- Direct connection to water resources: Because calcite forms from groundwater, the record directly reflects water availability — not just temperature.

This combination of qualities helps scientists refine predictions about drought, groundwater depletion, and ecological stress under modern climate change.

Final Thoughts

The Devils Hole study offers a powerful reminder that Earth’s climate system has always fluctuated — but the swings in the Southwest have often been dramatic, deeply affecting water and vegetation. As the region warms today, this half-million-year natural record provides important context and a warning about how sensitive desert ecosystems are to changes in rainfall and temperature.

Understanding these ancient patterns doesn’t just satisfy curiosity; it helps the modern Southwest prepare for a future where the balance between heat, water, and life may once again be pushed to its limits.

Research Paper:

Controls on the southwest USA hydroclimate over the last six glacial–interglacial cycles

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64963-1