New Research Shows Centuries-Long Drought, Not Ecocide, Reshaped Life on Easter Island

A new scientific study is offering the clearest evidence so far that a major and long-lasting climate shift—specifically a severe drought beginning around the mid-1500s—changed the course of life on Rapa Nui, commonly known as Easter Island. The research, led by scientists at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, uses an 800-year rainfall record preserved in lake and wetland sediments to challenge the long-popular idea that the island’s people destroyed their own environment in a dramatic ecological collapse. Instead, the findings point toward a more complex and far more human story—one shaped by adaptation, resilience, and a changing climate.

How Scientists Reconstructed Eight Centuries of Rainfall

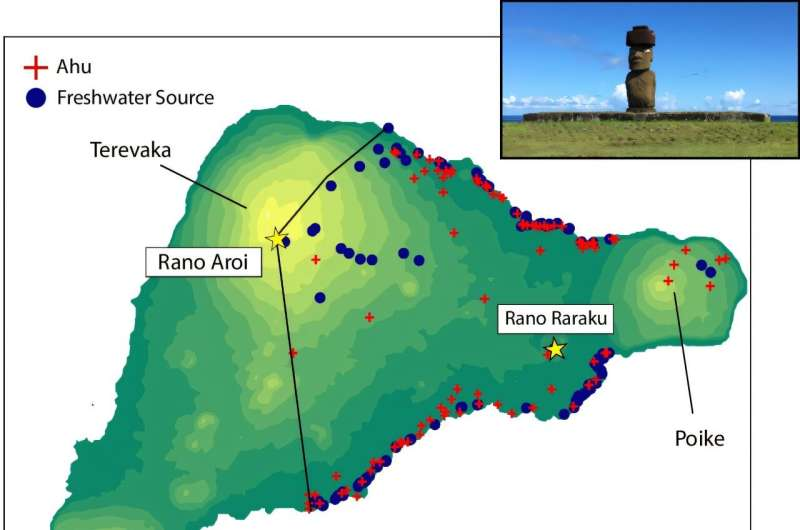

To understand what the climate looked like centuries before modern weather measurements, the research team extracted sediment cores from two of Rapa Nui’s rare freshwater sources: Rano Aroi, a high-elevation wetland, and Rano Kao, a crater lake. These wetland sediments accumulate slowly, storing biological and chemical traces of environmental conditions over time.

The researchers focused on the hydrogen isotope composition of leaf waxes—natural, long-lasting molecules produced by plants and preserved in the sediments. Because the ratio of heavy to light hydrogen in these waxes changes in parallel with the isotopic signature of rainfall absorbed by plants, the waxes provide a remarkably direct signal of past precipitation levels.

This method offers an advantage over other climate reconstruction tools like pollen, sediment accumulation rates, or elemental measurements, which can respond to multiple factors including human land use, changes in vegetation, or temperature. Leaf wax isotopes, by contrast, track rainfall and aridity in a more straightforward way, giving researchers a clearer picture of the climate patterns that shaped life on the island.

The Scale and Timing of the Drought

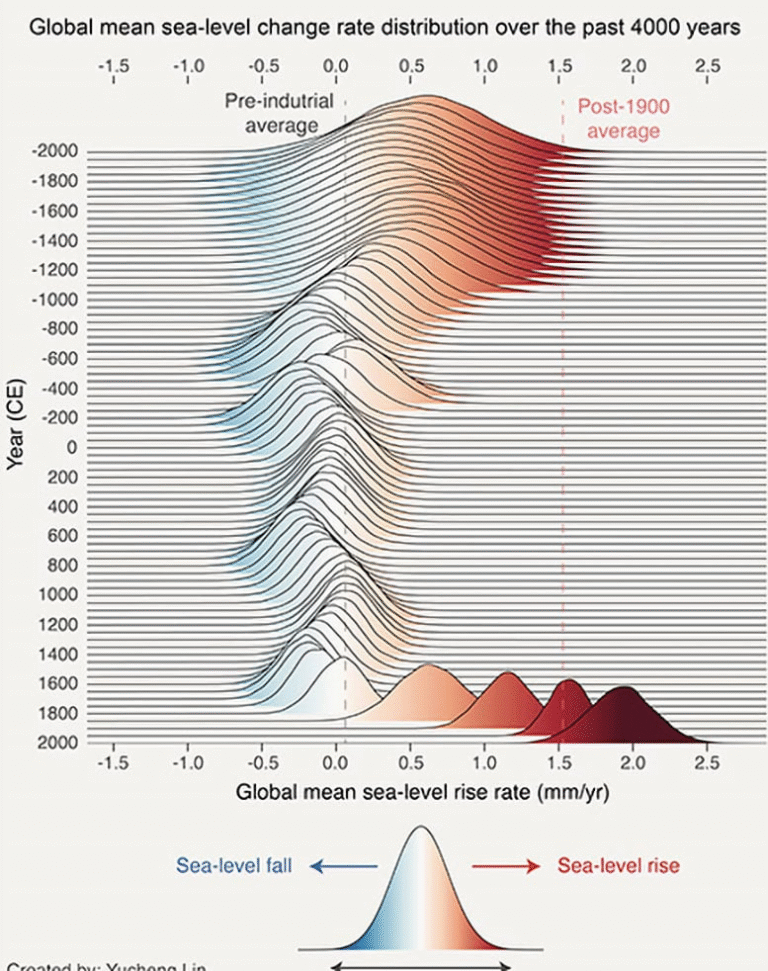

The analysis revealed a major drying trend starting around 1550 CE, with annual rainfall dropping roughly 600–800 mm—about 24 to 31 inches—below the levels seen during the previous 300 years. That is an enormous reduction for an island that today receives around 1,100 mm of rainfall annually.

This drought did not last a few seasons or even a few decades. It persisted for more than a century, deeply affecting an island already known for its limited freshwater resources. Rapa Nui’s volcanic bedrock causes rainwater to drain rapidly into the ground or ocean, making lakes, wetlands, and coastal seeps the only dependable sources of fresh water. A decline of this magnitude would have altered daily living, agriculture, ritual practices, and possibly patterns of land use.

Cultural Shifts That Coincided With the Drying Period

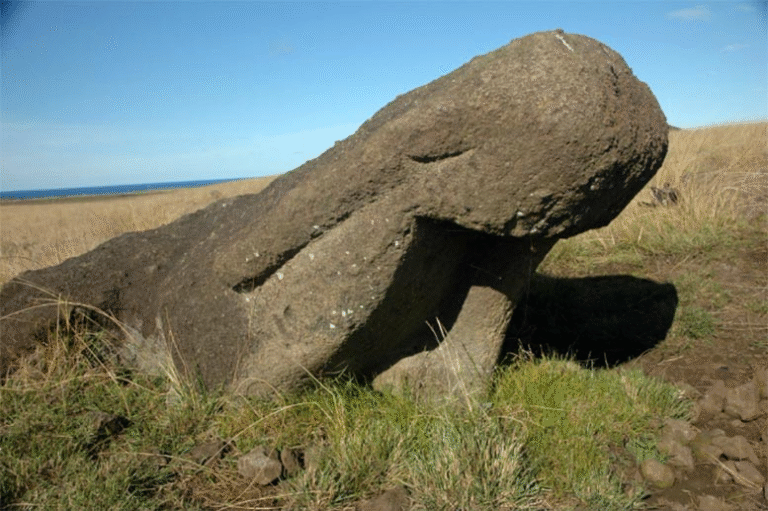

The timing of this severe drought aligns with major social and cultural transitions documented by archaeologists. One of the most noticeable changes is the decline in the construction of ahu—the ceremonial stone platforms that hold the iconic moai statues. These structures, associated with earlier political and ancestral traditions, became less common during the period when the climate was turning drier.

At the same time, new forms of ritual activity took root. Rano Kao, the large crater lake included in the sediment study, became an important ceremonial center. In addition, a new social system—Tangata Manu, or the Birdman tradition—rose to prominence. Unlike earlier hierarchies based on lineage tied to the moai, this later system relied on athletic competition to determine leadership.

The study does not claim that drought directly caused these changes, but the overlap in timing is hard to ignore. Environmental stress often acts as a backdrop against which societies shift their priorities, customs, and systems of governance.

Rethinking the “Ecocide” Narrative

For decades, popular books and documentaries have framed Rapa Nui as a cautionary tale of ecocide—the idea that its people cut down all their trees, ruined their ecosystem, and collapsed even before Europeans arrived. This narrative cast the islanders as people who destroyed their own environment through overconsumption.

But accumulating evidence has steadily undermined that story. Researchers have found little indication of a dramatic pre-European population crash. Instead, many studies show signs of continuity and adaptation rather than collapse.

This new drought-focused study strengthens the case that climate stress, not wholesale environmental mismanagement, influenced the island’s transitions. While it’s true that Rapa Nui gradually lost much of its forest cover, deforestation did not automatically mean societal collapse. The islanders appear to have adjusted, reorganized, and created new ritual systems rather than disappearing or descending into chaos.

The researchers emphasize that the goal is not to replace ecocide with a new oversimplified storyline. Instead, the aim is to reveal that the island’s history is far more nuanced. Climate variations created challenges. People responded in creative ways. Social systems evolved. That is a much more accurate—and more human—portrait.

Why Leaf Wax Records Matter for Climate Research

One particularly important aspect of this study is its methodological contribution. Leaf wax isotope analysis is considered one of the more direct ways to assess past precipitation patterns. On Rapa Nui today, rainfall isotopes are strongly tied to the number of large storms, which dominate annual rainfall totals. Because these storms account for more than 90% of precipitation variability on the island, leaf wax values reflect major shifts in storm activity and overall rainfall.

This makes Rapa Nui an ideal location for generating high-resolution climate records. The researchers even note that Rano Aroi preserves a much longer archive—stretching back 50,000 years—which could significantly improve our understanding of Southeast Pacific climate dynamics.

Why Rapa Nui Is a Unique Climate Archive

Rapa Nui is one of the most isolated inhabited places on Earth—over 3,000 km from Chile and more than 1,500 km from the next inhabited island. Because of this extreme isolation, it is the only place in a vast region of the Southeast Pacific where terrestrial sediments accumulate.

These sediments act like a natural climate observatory, offering insights into regional atmospheric circulation patterns that climate models often struggle to represent accurately. Understanding how the Pacific atmosphere responded to past climate forcings can help scientists improve predictions about future changes in rainfall and storm systems.

Lessons for Today’s Climate Challenges

The researchers stress that the best lessons are not about turning Rapa Nui into another parable of human failure or resilience. Instead, they highlight the value of listening to people in Rapa Nui and across the Pacific who are already experiencing the effects of modern climate change. Their lived experiences and knowledge systems offer more directly relevant guidance than historical extrapolations.

Still, the study does underline one key point: people are remarkably resilient. Rapa Nui’s history demonstrates that societies can innovate, reorganize, and survive even in the face of major environmental stress. While every society’s situation is different, this reminder of human adaptability is a meaningful takeaway in a changing world.

Looking Ahead: What Comes Next in This Research

With the much longer sediment record from Rano Aroi, the team plans to investigate how Southeast Pacific atmospheric circulation has shifted over tens of thousands of years. This could shed light on how regional climate systems respond to global climate forces—and help refine climate models that currently struggle with this remote region.

Research Paper:

Prolonged drought on Rapa Nui during the decline of megalithic monument construction

https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-025-02801-4