New Research Suggests Earth’s Deep Mantle Structures Formed Through Core–Mantle Mixing in Early Planet History

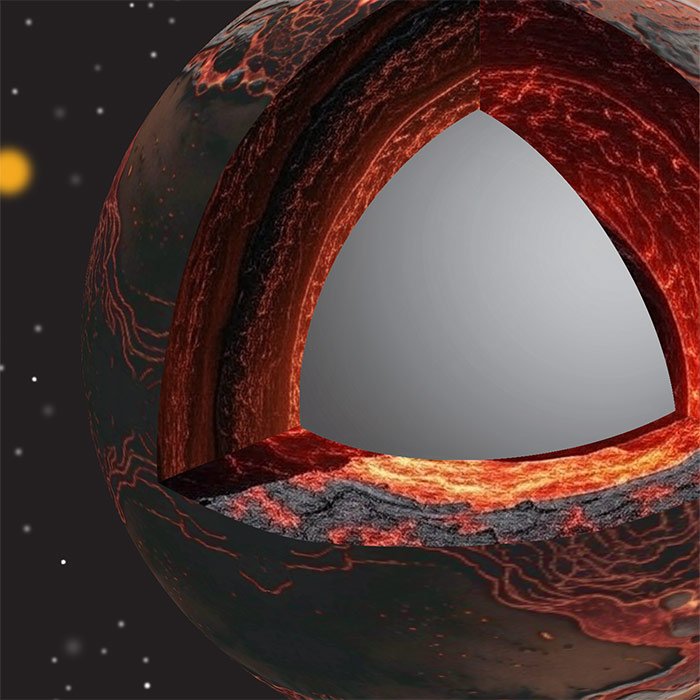

Scientists have long known about two gigantic features hidden nearly 1,800 miles beneath our feet—massive, strangely shaped regions at the boundary between Earth’s mantle and core. These formations, known as large low-shear-velocity provinces (LLSVPs) and ultra-low-velocity zones (ULVZs), have puzzled geophysicists for decades because their size, composition, and seismic behavior don’t match traditional models of how Earth evolved. Now, new research published in Nature Geoscience offers a compelling explanation that ties these mysterious structures to Earth’s earliest days and even to the planet’s long-term ability to support life.

Understanding the Deep-Earth Structures

LLSVPs are continent-sized masses of dense, hot material. One lies beneath Africa and the other stretches under the Pacific Ocean. They slow down seismic waves far more than surrounding mantle rock, indicating that they differ chemically or thermally—or both. Because of their unusual density and heat signatures, these features have been considered key to understanding how the mantle moves, how hotspots form, and how heat escapes from Earth’s interior.

Credit: Illustrated by Yoshinori Miyazaki

ULVZs, on the other hand, are thin, molten patches sitting directly above the core like puddles of lava. They are much smaller than LLSVPs but even more extreme in seismic behavior, slowing waves by up to 50 percent. Their presence suggests extremely hot, partially molten or chemically distinct material right at the core–mantle boundary.

Despite decades of research, scientists couldn’t fully explain why these features exist or how they acquired their unusual properties. Traditional models assumed Earth once had a global magma ocean covering its surface soon after formation. As this ocean cooled and solidified, the mantle should have formed neat, layered chemical zones—yet seismic data shows no such tidy layers today. Instead, we see these irregular, massive piles at the base of the mantle. Something didn’t add up.

A New Explanation: Core Material Leaking Into the Mantle

The new study, led by Rutgers geodynamicist Yoshinori Miyazaki in collaboration with researchers including Jie Deng of Princeton University, proposes that the missing piece of the puzzle is the core itself.

According to their model, during the early stages of Earth’s evolution, the boundary between the core and the overlying magma ocean wasn’t completely sealed. Elements such as silicon, magnesium, and other components gradually leaked out of the core into the molten lower mantle. Over billions of years, this mixing prevented the expected clean chemical layering and instead produced irregular, chemically complex piles—the LLSVPs and ULVZs we observe today.

The researchers describe these regions as remnants of a basal magma ocean contaminated by material exsolved from the core. Their simulations show how this mixture could evolve into the seismic anomalies now seen at the bottom of the mantle. This scenario also explains why previous magma-ocean models could not reproduce current mantle structure: they lacked the core-leakage component.

Why This Matters for Earth’s Evolution

This discovery has implications far beyond deep-Earth geology. If the core contributed chemically to the mantle early on, it would affect:

- How Earth cooled over time

- How mantle convection operates, influencing volcanic activity

- How hotspots form, such as those feeding Hawaii and Iceland

- How the atmosphere evolved, because volcanic outgassing shapes atmospheric composition

The study suggests that Earth’s internal behavior plays a major role in determining whether a planet becomes habitable. The researchers note that while Earth developed oceans, a stable climate, and a life-supporting atmosphere, Venus turned into a scorching greenhouse and Mars froze into a desert. Internal cooling and mantle-core interactions may help explain these differences.

Understanding these deep reservoirs is also crucial because they appear to hold a chemical memory of the early Earth. Volcanic rocks that sample deep mantle sources, such as those in Hawaii and Iceland, show unusual isotopic signatures. The new model explains how such chemical anomalies may be preserved for billions of years.

Additional Details From the Study

The research team used high-resolution geodynamic modeling to simulate billions of years of mantle evolution. Their models show:

- How a basal magma ocean would cool and solidify over time

- How core-derived material would reshape density and buoyancy patterns

- How LLSVP-scale structures could persist for long periods

- How ULVZs might form as thin, partially molten patches at the base of these piles

Snapshots of temperature and buoyancy fields at 0, 2.8, and 4.7 billion years show how the lower mantle gradually organizes into the kinds of structures detected by seismic imaging today.

Broader Context: Why LLSVPs Matter to Science

LLSVPs influence Earth in surprising ways:

- They may anchor mantle plumes, which carry heat from deep within the planet to the surface.

- They may contribute to supervolcano cycles by concentrating heat and directing plume formation.

- Their density and shape affect plate tectonics, since mantle flow interacts with them.

- They store chemical signatures that date back to Earth’s earliest stages, allowing researchers to reconstruct ancient planetary processes.

In short, these deep structures are not just oddities—they are essential pieces of Earth’s geological and biological story.

What Are Ultra-Low-Velocity Zones?

ULVZs may be even more intriguing:

- They consist of partially molten or iron-rich material, possibly created when core components accumulate in small pockets.

- They may represent localized chemical reservoirs that interact with both the core and the overlying mantle.

- They can affect how heat escapes through the core–mantle boundary, which ties directly to the behavior of the geodynamo—the engine that powers Earth’s magnetic field.

Because the magnetic field protects life from harmful solar radiation, these deep-Earth processes indirectly influence conditions at the surface.

The Study’s Bigger Message

This research highlights a remarkable idea: even with limited direct evidence—since nobody can drill 1,800 miles down—scientists are beginning to piece together a coherent picture of Earth’s earliest days. By combining seismic data, mineral physics, and long-term geodynamic modeling, they’re showing that Earth’s deep interior still holds clues about why the planet is uniquely suited for life.

The researchers describe their findings as turning scattered observations into a clearer narrative of early planetary evolution. Knowing how these deep structures formed sheds light on why Earth’s environment stabilized in a way that allowed oceans, continents, and life to emerge.