New Study Shows Huge Differences in How Soil Carbon Breaks Down Across the United States

A new scientific study has taken a deep look at how organic carbon decomposes in U.S. soils, and the findings show something far more complex than scientists previously assumed. Soil holds more carbon than the atmosphere and all plant life combined, so understanding how quickly that carbon breaks down—and how much ends up back in the air as carbon dioxide—is a big deal for climate predictions. This research, published in One Earth by a team that includes four Iowa State University scientists, reveals that soil carbon decomposition rates can vary up to tenfold, even when samples are placed under the exact same laboratory conditions.

This level of variation challenges long-standing assumptions used in major Earth system models—the complex simulations scientists rely on to estimate how ecosystems and the climate interact. For years, models have tended to simplify soil carbon decay by assuming that soils of similar type or within the same biome break down carbon at similar baseline rates, as long as environmental conditions like temperature and moisture remain constant. But the new findings show that this widely used simplification doesn’t match reality.

Why the Decomposition Rate Varies So Much

To understand the natural differences in soil carbon behavior, the research team incubated soil samples from 20 National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON) sites across the United States. These sites cover a wide range of climates, soil types, and ecosystems. The samples came from two soil depths—0–15 cm and 15–30 cm—and were observed for 18 months in a controlled laboratory setup. During the incubation, scientists tracked carbon dioxide emissions and collected 26 different measurements describing the chemical, physical, and biological properties of each soil.

Machine-learning methods helped researchers determine which of those measurements best explained why carbon decomposed faster in some soils than others. Several well-known factors were confirmed, such as soil pH, levels of nitrogen, and broad soil type categories. But the study also highlighted the surprisingly strong role of soil minerals and microbial communities, especially fungi and specific forms of iron and aluminum. These minerals are particularly important because they influence the stability of mineral-associated organic carbon (MAOC), a long-lasting carbon pool that can stay in soil for decades or centuries.

The soils were examined in terms of two key carbon pools:

- Particulate organic carbon (POC) – mostly plant-derived, decomposes relatively quickly (years to decades).

- Mineral-associated organic carbon (MAOC) – protected by minerals, decomposes much more slowly (decades to centuries).

Different soils contain different proportions of these carbon pools, and they behave differently during decomposition. The study shows that models must account for both types rather than treating soil carbon as a single uniform category.

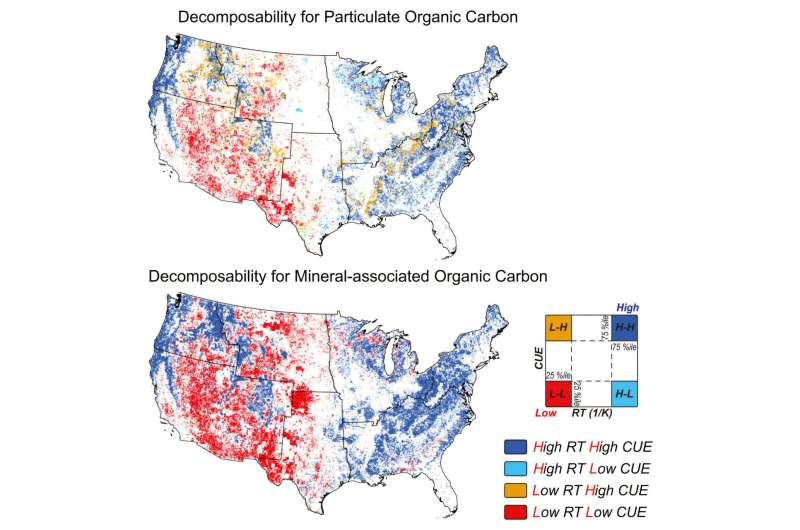

Building AI-Powered Maps of Soil Carbon Behavior

Once the team identified the key controlling factors, they used them to build AI-based models capable of predicting two important metrics:

- Baseline decay rate – how fast organic matter breaks down

- Carbon-use efficiency (CUE) – how much decomposed carbon ends up stored in microbial biomass instead of being released as CO₂

They applied these models to soils across the entire continental United States, producing high-resolution maps (each pixel representing about 2.5 miles by 2.5 miles) showing how decomposition rates and CUE vary by region. These maps reveal major geographic differences:

- In the Southwest, soils tend to have faster decomposition rates and lower CUE, meaning more carbon ends up released into the atmosphere.

- In the Northwest and Eastern U.S., decomposition is generally slower, and microbes tend to convert more decomposed carbon into biomass, effectively keeping more carbon in the soil.

- The Midwest tends to fall between these two extremes.

These regional differences highlight that soil carbon vulnerability—and the long-term stability of stored soil carbon—varies widely across the country.

What This Means for Climate Models

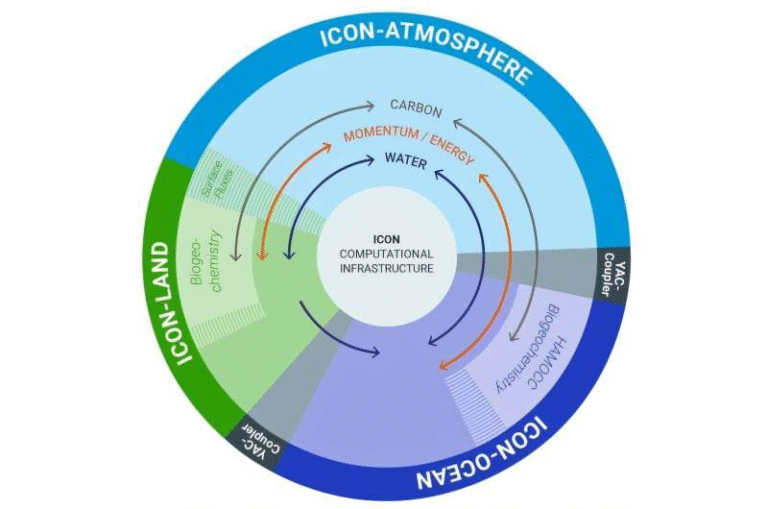

Earth system models play a critical role in predicting future climate change, particularly the feedback loops between land ecosystems and the atmosphere. Soil carbon is one of the hardest pieces of the climate puzzle because it depends on countless biological and chemical processes occurring beneath our feet.

This study shows that models have been underrepresenting key drivers, especially geochemical and microbial factors. By integrating soil mineral properties, fungal abundance, and more specific soil-carbon pool dynamics, climate simulations could produce far more accurate estimates of how much carbon soil will release or retain under changing conditions.

Smaller errors in soil carbon predictions can translate into meaningful differences in projected future atmospheric carbon concentrations. For climate modeling, reducing uncertainty is enormously valuable.

Implications Beyond Climate Models: Conservation and Carbon Markets

The findings are not just useful for global climate predictions—they also matter for anyone working on carbon sequestration, soil conservation, or carbon-credit markets.

Because the stability of soil carbon varies from region to region, the value of storing carbon in soils is not the same everywhere. A ton of carbon added to soil in a region with high retention might remain there far longer than a ton stored in a region with rapid decomposition.

This means incentive programs may need to consider:

- Carbon retention persistence

- Regional differences in soil mineralogy

- The proportion of MAOC vs. POC in local soils

If policymakers and carbon-market designers account for these differences, carbon-sequestration strategies could become much more effective and scientifically grounded.

Additional Background: Why Soil Carbon Matters So Much

Soils globally contain more than twice as much carbon as the atmosphere. The carbon enters the soil through plant roots, leaf litter, microbial activity, and long-term natural accumulation. When soil microbes break down organic matter, they release CO₂—so the balance between carbon input and carbon loss determines whether a soil is acting as a carbon sink or a carbon source.

Several factors influence this balance:

- Temperature – warmer soils typically decompose faster.

- Moisture – too wet or too dry can slow decomposition.

- Soil texture – clay-rich soils often protect carbon more effectively.

- Microbial activity – bacteria and fungi are the engines of decomposition.

- Land use – tilling, deforestation, and erosion all influence carbon dynamics.

Because so many factors shape soil carbon behavior, scientists have spent decades trying to understand which variables matter most, and how to correctly incorporate them into climate models. This new research helps narrow that uncertainty by showing that mineral-organic interactions and microbial traits are far more important than previously assumed.

A Clearer Picture of Soil Carbon Vulnerability

One of the standout contributions of this study is that it separates the decomposability of two major soil carbon pools. This is crucial because mineral-associated carbon is the pool most likely to help long-term climate mitigation efforts. If we know which regions have soil with higher MAOC stability, we can better identify where carbon-storage efforts will have the strongest impact.

Meanwhile, regions dominated by particulate carbon may struggle to hold carbon for long periods unless management strategies actively shift soil characteristics.

These findings emphasize that soil carbon isn’t a single thing—it’s a mix of substances with very different lifespans, controlled by a wide range of physical, biological, and chemical factors.

Research Article Link

Research Paper:

Joint geochemical and microbial controls on decomposability of soil particulate and mineral-associated organic carbon across the contiguous US

https://www.cell.com/one-earth/fulltext/S2590-3322(25)00342-2