New Tool Lets Anyone Audit a Country’s Methane Claims

For decades, countries around the world have reported their methane emissions to the United Nations using a fairly traditional method. Governments start from the ground up: they count livestock, estimate oil and gas production, measure landfill waste, and then apply standardized emission factors to calculate how much methane they believe is entering the atmosphere. This approach, often called bottom-up accounting, has been the backbone of national climate reporting under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

But methane, unlike many other pollutants, has a habit of slipping through the cracks—literally. Increasingly precise measurements from aircraft and satellites suggest that official inventories often miss a significant share of real-world emissions. Until recently, translating those atmospheric measurements into national-level emission estimates required deep technical expertise and specialized modeling tools, putting independent verification out of reach for most people.

That is now changing. A research team led by scientists at Harvard University has developed a new open-access system called Integrated Methane Inversion (IMI), designed to let governments, researchers, and even civil society independently check how well national methane claims line up with what satellites actually observe in the atmosphere.

Why Methane Matters So Much

Methane has emerged as one of the most important targets in climate policy. While carbon dioxide stays in the atmosphere for centuries, methane is much more potent in the short term. Over the first few decades after it is released, methane traps far more heat than CO₂, making it a powerful driver of near-term warming. Scientists estimate that methane is responsible for around 30% of global temperature rise since the Industrial Revolution.

Most methane emissions come from human activities. These include oil, gas, and coal extraction, livestock digestion, rice cultivation, and the decomposition of organic waste in landfills. Because methane has a relatively short atmospheric lifetime, cutting emissions can slow warming quickly—making accurate measurement and accountability especially important.

The Limits of Traditional Reporting

National methane inventories rely heavily on assumptions. For example, a country may estimate emissions from oil and gas production by multiplying production volumes by average leakage rates. The problem is that leakage rates vary widely depending on infrastructure quality, maintenance, regulation, and enforcement. As a result, official reports can differ sharply from what atmospheric measurements suggest.

Aircraft campaigns and satellites have revealed large methane plumes over oil fields, gas pipelines, landfills, and other sources that are either underestimated or entirely missing from national inventories. Until now, however, there has been no easy, standardized way to turn that observational data into country-by-country emissions figures that anyone could examine.

How Integrated Methane Inversion Works

IMI takes a top-down approach. Instead of starting with economic activity data, it begins with methane concentrations measured directly in the atmosphere. The system uses satellite observations from multiple instruments, combining them in a way that allows the datasets to correct each other’s biases.

The process starts with the methane emissions that countries have already reported to the UNFCCC. These reported figures serve as a baseline, or “prior.” IMI then adds emission sources that are often excluded from national inventories, such as hydroelectric reservoirs, which can emit methane as organic matter decomposes underwater.

Next, the system integrates high-resolution satellite detections of known methane hotspots, giving extra weight to areas where emissions are clearly visible from space. All of this information is fed into an atmospheric transport model that simulates how methane moves through the atmosphere and how it is broken down over time.

The model repeatedly adjusts emissions across different locations and sectors until the simulated methane concentrations best match what satellites actually observe. The result is a set of updated emissions estimates, along with uncertainty ranges that show how confident the system is in each number.

What the First Global Results Showed

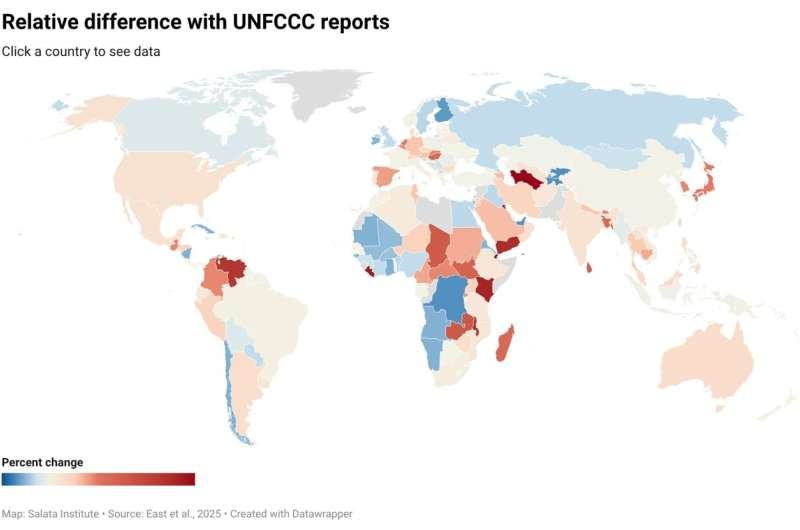

The research team applied IMI globally for the year 2023, examining methane emissions across 161 countries. The findings revealed widespread discrepancies between official inventories and atmospheric observations.

In roughly one-quarter of the countries studied, methane emissions appeared to be more than 50% higher than what governments had reported. Some of the most striking differences showed up in the oil-and-gas sector. In Venezuela, emissions from oil and gas were estimated to be 4.8 times higher than official figures. In Turkmenistan, they were 3.8 times higher. The United States, which is the world’s largest absolute methane emitter, showed emissions about 1.55 times higher than reported.

Venezuela stood out not just for the size of the discrepancy, but for what it revealed about infrastructure performance. The researchers estimated that as much as 29% of the gas produced in Venezuela may be escaping into the atmosphere. This metric, known as methane intensity, provides a measure of how much methane is leaked relative to production. For comparison, methane intensity is estimated at 2.1% in the United States and just 0.1% in Qatar, where modern, concentrated infrastructure allows gas to be captured more efficiently.

Global Emissions Are Higher Than We Thought

When all countries and sectors were combined, IMI estimated total anthropogenic methane emissions of about 375 million metric tons in 2023, roughly 15% higher than official global figures.

The system also highlighted major differences across sectors. Global methane emissions were revised upward for oil and gas (by 32%), livestock (17%), waste (16%), and rice cultivation (26%). In contrast, emissions from coal mining were revised downward by 23%, suggesting that some sources may be overestimated in traditional inventories.

Hydroelectric reservoirs, which are frequently omitted from national reports, accounted for about 6% of global human-caused methane emissions, underscoring how incomplete some inventories can be.

Transparency, Accountability, and the Bigger Picture

Beyond the numbers themselves, the most important contribution of IMI may be its repeatability and openness. The system is fully open source, transparent, and designed to be usable by people without advanced degrees in atmospheric science. This means that methane accounting no longer has to be confined to a small group of specialists.

IMI can consistently flag where national inventories appear too low, too high, or outdated. Governments can use this information to revisit their activity data, improve emission factors, and track whether emissions are moving in the direction promised under climate plans.

The researchers also point out that the system is resilient to political shifts. Even if a country withdraws from formal climate agreements or stops reporting to the UNFCCC, IMI can continue to update emissions using public data and satellite observations, supporting independent climate accountability outside official treaty processes.

Why Tools Like IMI Are Likely to Matter More

As satellite technology continues to improve, the gap between what is reported and what is observed will become harder to ignore. Tools like IMI suggest a future where greenhouse gas reporting is not just a matter of trust, but of verifiable evidence. For methane—a gas where rapid reductions could deliver quick climate benefits—this kind of transparency could play a critical role in shaping policy, investment, and enforcement.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67122-8