Researchers Find Lower Levels of Microplastics in Southern Narragansett Bay Compared to the North

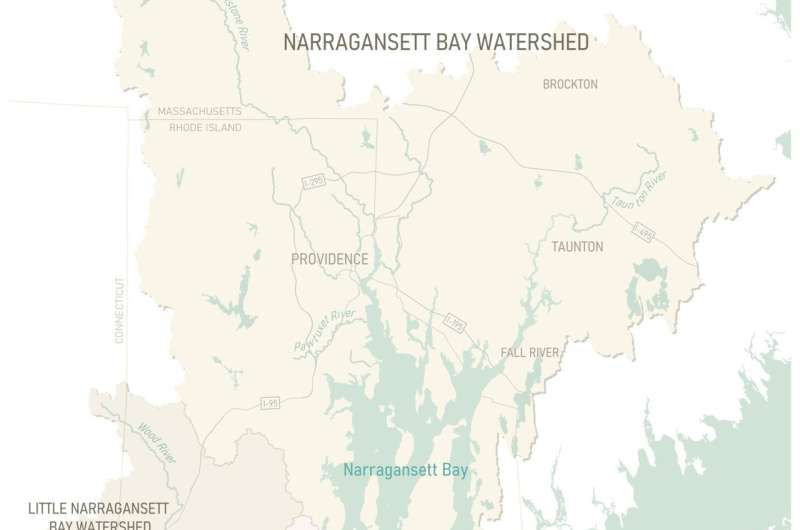

Researchers from the University of Rhode Island (URI) have uncovered new insights into how microplastics are distributed across Narragansett Bay, and the findings highlight a clear geographic divide. According to their study, the northern section of the bay contains significantly higher concentrations of microplastics than the southern portion, a difference closely tied to human population density, river runoff, and ocean circulation.

Narragansett Bay, a 147-square-mile tidal estuary, is central to Rhode Island’s identity as the Ocean State. For centuries, it has supported fishing, recreation, tourism, and coastal communities. However, the same human activity that depends on the bay has also contributed to its growing burden of plastic pollution, particularly in the form of microplastics.

Why Microplastics Are More Concentrated in the Northern Bay

The research shows that freshwater rivers flowing through urban areas play a major role in transporting microplastics into the bay. Rivers that pass through densely populated regions, especially around Providence and other northern communities, collect plastic debris from urban runoff, wastewater discharge, and everyday product use. Over time, these plastics break down into tiny fragments and are deposited into the bay’s waters.

In contrast, the southern part of Narragansett Bay experiences lower levels of microplastics. One major reason is population distribution. Fewer people live along the southern shoreline, which naturally leads to less plastic entering nearby waterways. Additionally, the southern bay is closer to the open ocean, allowing tidal exchange to flush out microplastics more regularly, preventing them from building up to the same degree seen in the north.

This north-to-south gradient is not new. Researchers note that spatial differences in microplastic accumulation have persisted for decades, even as overall plastic pollution has increased dramatically since the mid-20th century.

How the Study Was Conducted

The research was led by Sarah M. Davis, a postdoctoral research fellow at URI, and Victoria Fulfer, a researcher affiliated with the 5 Gyres Institute, an organization focused on reducing plastic pollution worldwide. Their findings were also shared publicly as part of Rhode Island Sea Grant’s Coastal State Series, a program designed to highlight marine research relevant to the state.

To gather data, the research team conducted surface water sampling over two years, collecting samples during three seasonal periods: winter, spring, and a combined summer–fall season. Using surface-water trawls, they collected two replicate samples at each site, resulting in a total of 72 unique trawls across Narragansett Bay.

This multi-season approach allowed researchers to account for seasonal variability, such as changes in river flow, stormwater runoff, and wind-driven circulation patterns, all of which influence how microplastics move through estuarine waters.

Long-Term Trends in Microplastic Pollution

Microplastic pollution in Narragansett Bay has been steadily increasing since the 1950s, mirroring national and global trends in plastic production and consumption. Plastics introduced decades ago continue to fragment into smaller pieces, adding to the growing load of microplastics already present in the ecosystem.

One of the most striking findings from related research is how different environments within the bay trap microplastics at different rates. Marshes, for example, were found to contain 10 to 50 times more microplastics than nearby seafloor sediments. These wetlands act like natural filters, capturing floating debris that becomes embedded in vegetation and sediments.

The researchers sampled marshes near Providence as well as two marshes on Conanicut Island, home to the town of Jamestown. While the marsh near Providence had the highest microplastic concentrations, even the Jamestown marshes—located in less densely populated areas—contained higher microplastic levels than adjacent seafloor areas.

Microplastics Beneath the Bay Floor

This study builds on earlier work by the same research team. In 2023, Victoria Fulfer co-authored a study estimating that the top two inches of Narragansett Bay’s seafloor contain more than 1,000 tons of microplastics. This finding highlights how microplastics don’t just float at the surface; they also accumulate and persist in sediments, where they can remain for decades.

The combined research paints a picture of a bay where microplastics are widespread, increasing, and unevenly distributed, shaped by human activity and natural environmental processes.

Environmental and Potential Health Impacts

Microplastics are defined as plastic particles smaller than 5 millimeters, and they have become one of the most pervasive pollutants in marine environments. Scientists have now detected microplastics almost everywhere, including oceans, freshwater systems, wildlife, and even the human body. While the full impact on human health is still being studied, environmental effects are already well documented.

Marine organisms often mistake microplastics for food, which can lead to digestive blockages, reduced feeding efficiency, and impaired nutrient absorption. Microplastics can also act as carriers for toxic chemicals and pollutants, potentially amplifying their harmful effects as they move through the food web.

What These Findings Mean for Pollution Management

Understanding where microplastics accumulate most heavily can help guide targeted pollution reduction strategies. The researchers suggest that efforts to reduce microplastic pollution in Narragansett Bay should focus on urban runoff management, especially in freshwater rivers that feed into the northern bay.

Improving wastewater treatment systems, particularly during periods of high river flow, could significantly reduce the amount of microplastics entering the bay. Because estuaries like Narragansett Bay are dynamic systems, even small reductions in upstream inputs can have meaningful downstream benefits.

Additional Context: Why Estuaries Are Microplastic Hotspots

Estuaries are especially vulnerable to microplastic pollution because they sit at the intersection of land and ocean systems. Rivers deliver plastic debris from inland sources, while tides and currents redistribute particles throughout the estuary. Areas with slower water movement, such as marshes and sheltered coves, are particularly effective at trapping microplastics.

Narragansett Bay’s combination of urbanized watersheds, extensive marshlands, and complex circulation patterns makes it an important case study for understanding how microplastics behave in coastal environments worldwide.

Looking Ahead

While the lower levels of microplastics in southern Narragansett Bay are encouraging, researchers emphasize that no part of the bay is free from plastic pollution. The study reinforces the idea that reducing plastic use and improving waste management on land are essential steps toward protecting coastal ecosystems.

As scientists continue to refine sampling methods and modeling tools, studies like this provide critical data for policymakers, environmental managers, and the public. Narragansett Bay’s story is not just a local issue—it reflects a global challenge faced by coastal waters everywhere.

Research Paper:

Comparing field-based microplastic observations with ocean circulation model outputs in estuarine surface waters along a human population gradient

Marine Pollution Bulletin (2025)

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2025.118224