Rocks and Rolls How Advanced Imaging From the Air Is Changing Earthquake Science and Planetary Physics

Understanding Earth’s most powerful and unpredictable processes often requires scientists to zoom out before they can truly zoom in. That idea sits at the heart of recent work led by Andrea Donnellan, a leading Earth scientist and seismologist who studies earthquakes, glaciers, and the shifting surface of our planet from far above the ground. By combining aircraft-based imaging, spaceborne observations, and advanced computation, her research is helping scientists better understand how Earth moves, where it might break, and why some motion is dangerous while other motion is surprisingly quiet.

Donnellan is a professor and head of the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences at Purdue University’s College of Science. Over the years, her work has spanned continents and disciplines, from Antarctica’s glaciers to California’s active fault systems. The unifying theme across her research is a focus on precision measurement and the belief that Earth’s landscapes preserve a detailed record of geological history.

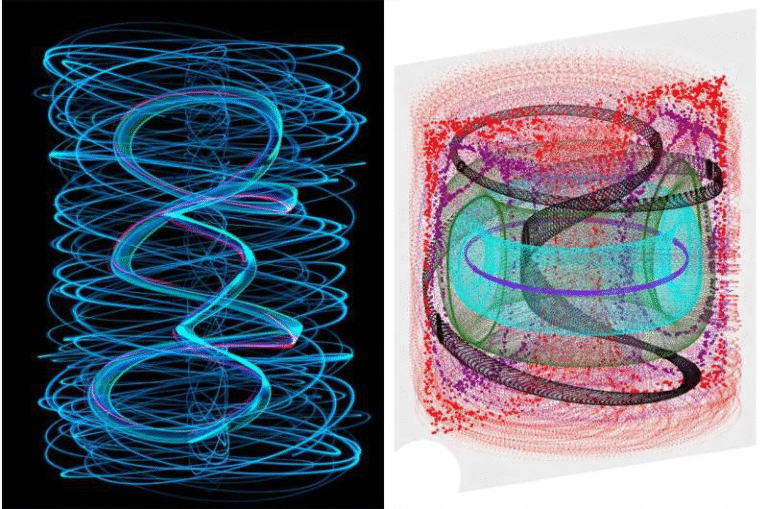

Earth’s surface is constantly changing, even when those changes are nearly invisible. Advances in GPS technology have transformed how scientists observe these motions. What once could only be measured in meters can now be detected in millimeters, allowing researchers to track slow-moving glaciers, subtle tectonic strain, and gradual shifts along faults with extraordinary accuracy. These measurements form the foundation for understanding the physics that drive earthquakes and other geological events.

A New Eye in the Sky Called QUAKES-I

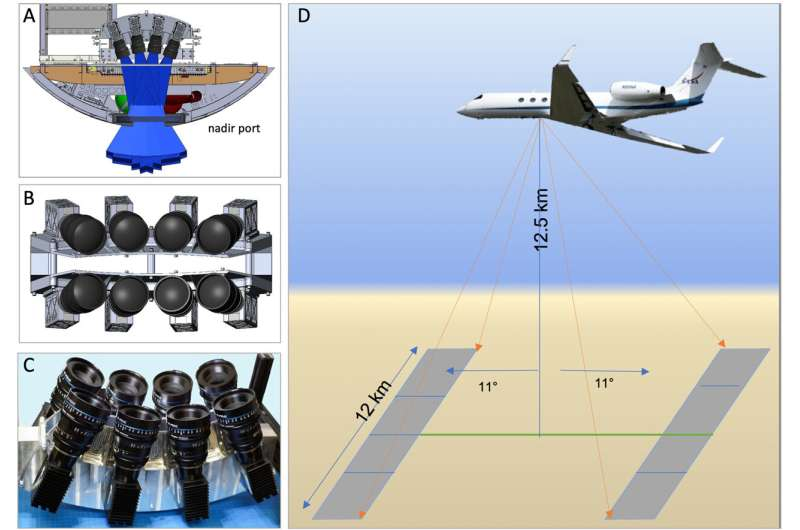

At the center of Donnellan’s latest work is a newly developed airborne instrument known as QUAKES-I, short for Quantifying Uncertainty and Kinematics of Earth Systems Imager. The instrument was recently detailed in a scientific paper published in Earth and Space Science.

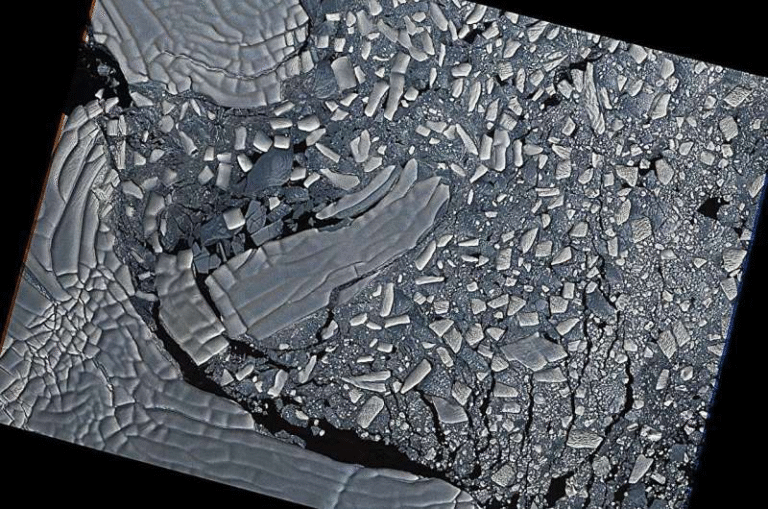

QUAKES-I is designed to collect high-resolution, color, three-dimensional maps of Earth’s surface by flying aboard an aircraft at around 41,000 feet. Rather than relying on a single camera, the system uses eight synchronized cameras mounted in a nadir port on the underside of a Gulfstream V aircraft. These cameras look straight down at the ground, capturing overlapping images that can be processed into detailed 3D models.

Each camera uses 35 mm CMOS sensors paired with 100 mm lenses, global shutters, and Bayer-patterned sensors capable of both 8-bit and 10-bit imaging. The resulting images are 5,120 by 3,840 pixels, or about 20 megapixels each. When combined, these images create a wide and detailed view of the terrain below.

From its cruising altitude, QUAKES-I captures a 12-kilometer-wide swath of land in a single pass. Scientists then divide this large area into 10-by-12-kilometer sections for analysis. This approach strikes a careful balance between resolution and coverage, offering more detail than many satellites while still mapping large regions efficiently.

Why Aircraft Still Matter in Earth Observation

Satellites often dominate conversations about Earth observation, but aircraft play a critical role. As scientists move closer to the ground, they gain resolution but lose coverage. Satellites offer broad views but may lack the fine detail needed for certain studies. Aircraft like the Gulfstream V fill this gap, providing high-resolution data over targeted regions on relatively short notice.

QUAKES-I’s airborne design also allows for rapid deployment, making it especially useful after natural disasters such as earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, or wildfires. Researchers can gather fresh data quickly, capturing surface changes before weather, erosion, or human activity alter the landscape.

The color imagery provided by QUAKES-I adds another layer of value. While lidar excels at measuring elevation and radar is excellent for detecting deformation, color stereo imagery provides visual context that helps scientists interpret terrain features, vegetation, infrastructure, and surface damage. Rather than replacing other technologies, QUAKES-I complements them.

Part of a Bigger NASA Vision

QUAKES-I is not a standalone effort. It is an airborne component of NASA’s Surface Topography and Vegetation incubation program, an ambitious initiative developing a future constellation of radar, lidar, and stereoimaging instruments. The goal is to create the most detailed and dynamic digital map of Earth’s surface ever produced.

By combining multiple measurement techniques, scientists can better understand how Earth’s surface responds to tectonic forces, erosion, climate change, and human activity. QUAKES-I helps test and refine stereoimaging methods that may one day be used in spaceborne missions.

The instrument can also be mounted on different aircraft and flown alongside other sensors, increasing its flexibility. While NASA pilots operate the larger aircraft, Donnellan herself also uses drones for even higher-resolution observations at smaller scales.

From Mapping to Earthquake Science

One of the most important applications of QUAKES-I lies in earthquake research. Unlike weather events, earthquakes remain notoriously difficult to forecast. While scientists understand where major faults lie, predicting exactly when and how an earthquake will occur is still beyond reach.

Donnellan’s work focuses on measuring strain and motion along tectonic faults and examining how surrounding landscapes influence seismic behavior. Some earthquakes occur along well-known fault lines, such as California’s San Andreas Fault, but many others strike in less obvious locations.

In recent years, earthquakes have been recorded in 38 U.S. states, highlighting how widespread seismic risk really is. Even regions not traditionally associated with earthquakes can experience damaging events, making better hazard assessment increasingly important.

A key insight from Donnellan’s research is that not all motion in the Earth’s crust is destructive. Some movement occurs slowly and quietly, releasing energy without causing strong shaking. Distinguishing between this quiet motion and motion that leads to damaging earthquakes is one of the central challenges in modern seismology.

By combining precise surface measurements with topographic context, researchers hope to better understand how stress builds up and is released along faults. This knowledge could eventually improve earthquake hazard models, helping communities design safer infrastructure and prepare more effectively for future events.

Beyond Earthquakes What Else QUAKES-I Can Study

Although earthquakes are a major focus, QUAKES-I has a wide range of applications. Its high-resolution maps are valuable for studying volcanoes, glaciers, erosion, landslides, wildfires, ecosystems, infrastructure, and vegetation. Changes in terrain can reveal how landscapes respond to natural disasters and long-term environmental pressures.

For example, glacier movement and thinning can be tracked over time, offering insights into climate change. Wildfire scars and erosion patterns can be mapped in detail, helping scientists understand recovery processes and future risks. Infrastructure damage following earthquakes or floods can also be assessed quickly and accurately.

Why Computational Infrastructure Matters

Behind the cameras and aircraft lies a powerful computational backbone. Turning thousands of overlapping images into precise 3D maps requires advanced processing techniques and significant computing power. These digital models allow scientists to compare landscapes across time, detect subtle changes, and test physical models of Earth processes.

In this sense, QUAKES-I represents more than just a new instrument. It is part of a broader shift toward data-rich, computation-driven Earth science, where high-resolution observations and advanced analytics work hand in hand.

Looking Ahead

By watching Earth from above with increasing clarity, scientists like Andrea Donnellan are rewriting how we understand the planet beneath our feet. The combination of airborne imaging, satellite data, and computational modeling is opening new doors in earthquake science and planetary physics.

While predicting earthquakes with precision remains a long-term challenge, tools like QUAKES-I are bringing researchers closer to understanding where risk lies, how landscapes record past events, and how future hazards might unfold. In doing so, they contribute to a safer and more informed relationship between humanity and an ever-changing Earth.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1029/2024EA004001