Satellite Data Reveals How Sustainable Groundwater Use in the Hollywood Basin May Be Lower Than Expected

Groundwater has become one of the most important resources in Southern California, especially as long-term drought, rising temperatures, and climate variability continue to strain imported water supplies. In this context, a new Caltech-led scientific study has taken a close look at the Hollywood Basin, a relatively small but critical groundwater system beneath parts of Los Angeles, and the findings suggest that current assumptions about how much water can safely be pumped may be far too optimistic.

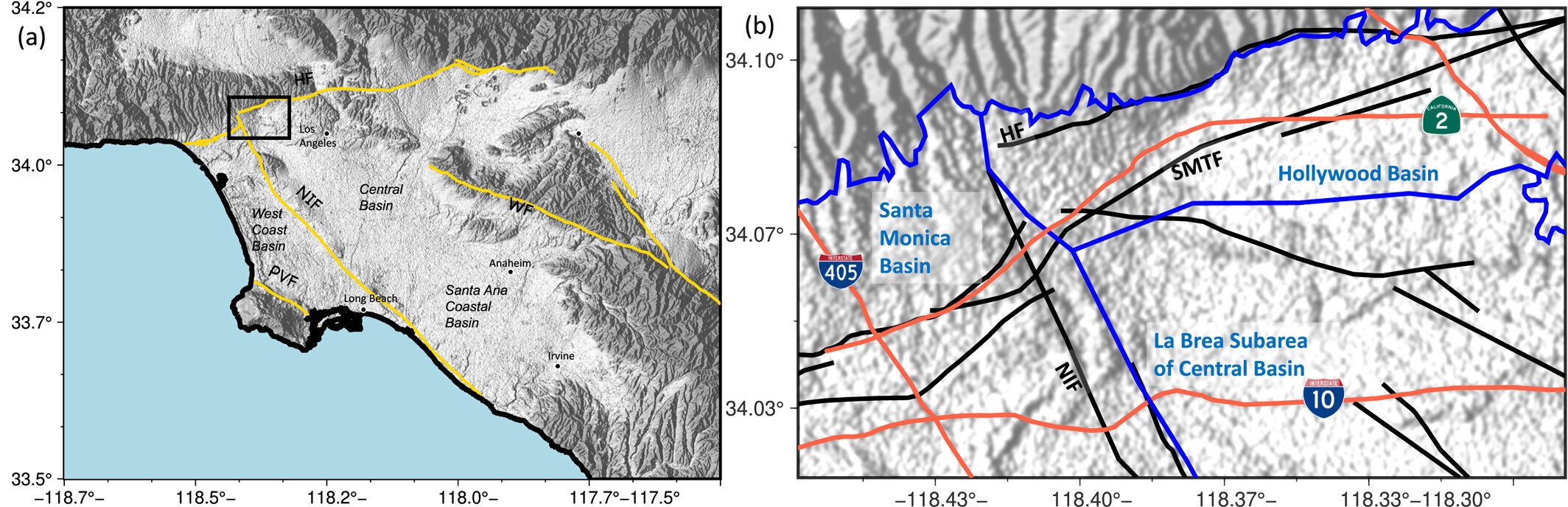

The Hollywood Basin sits beneath and around the West Hollywood area and has increasingly been used as a local water source to reduce dependence on water imported from distant rivers and reservoirs. Until now, understanding how this aquifer responds to pumping has been difficult due to limited monitoring infrastructure. By using three decades of satellite observations, researchers have now pieced together the most detailed picture yet of how groundwater extraction physically affects the land above it—and what that means for sustainable water management.

Why the Hollywood Basin Matters

Southern California relies heavily on imported water from places like the Colorado River and Northern California. As these supplies become less reliable, cities are turning back to local groundwater. The Hollywood Basin, though small compared to major California aquifers, plays an important role for nearby communities, including Beverly Hills.

The basin’s main aquifer lies about 600 feet underground and is estimated to contain roughly 65 billion gallons of water. This water fills the tiny spaces between underground materials such as sand, gravel, and clay. When pumped responsibly, it can provide drinking water and help buffer against drought. When overused, however, it can cause permanent damage, including land subsidence and loss of underground storage capacity.

Using Satellites to Track Groundwater

The study relied on a satellite-based technique called InSAR, short for Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar. In simple terms, InSAR uses radar pulses sent from satellites to measure how the Earth’s surface moves over time—sometimes by just a few millimeters.

These subtle movements turn out to be extremely valuable. When groundwater is pumped out of an aquifer, the ground above it can sink slightly. When water is replenished, the ground can rebound. By analyzing these patterns over time, scientists can infer how groundwater levels change even without direct measurements from wells.

Over the past 30 years, multiple satellite missions have collected InSAR data across the Los Angeles region. The research team combined this long-term satellite record with historical groundwater production data to understand how pumping in the Hollywood Basin has affected land motion.

Clear Links Between Pumping and Land Movement

The satellite record showed a direct and consistent relationship between groundwater pumping and ground movement in the Hollywood Basin. When pumping was reduced or stopped, the land surface rebounded. When pumping resumed, subsidence returned.

This strong correlation allowed researchers to reconstruct a detailed, three-decade history of how the basin has responded to water extraction. Importantly, this approach worked even though the Hollywood Basin lacks a dense network of monitoring wells and is not subject to some of California’s stricter groundwater reporting requirements.

Rethinking “Safe” Groundwater Yield

One of the most significant outcomes of the study is a revised estimate of how much groundwater can be pumped sustainably. The City of Beverly Hills currently cites a safe yield of about 3,000 acre-feet per year, based largely on data from a small number of wells.

The satellite-based analysis paints a very different picture. According to the study, the Hollywood Basin’s true sustainable yield is closer to 1,200–1,400 acre-feet per year. Pumping beyond this range increases the risk of permanent compaction of underground materials, which reduces the aquifer’s ability to store water in the future.

While much of the basin still behaves elastically—meaning it can recover when pumping stops—localized zones near production wells already show signs of permanent deformation. This indicates that parts of the aquifer may be losing storage capacity for good.

Why This Matters for Water Management

Groundwater management has traditionally relied on water-level data from monitoring wells. In small basins like Hollywood, such data is often sparse, incomplete, or entirely absent. This study demonstrates that satellite data can fill those gaps, offering an independent and region-wide way to assess aquifer health.

This approach is especially relevant as climate change introduces more extremes—longer droughts followed by unusually wet years, such as the 2022–23 atmospheric river season in California. These swings make it harder to plan groundwater use based on short-term observations alone.

With new missions like NISAR, a joint project between NASA and the Indian Space Research Organisation, scientists expect even more frequent and higher-quality satellite data to become available. This could allow water managers to monitor aquifers almost in real time.

An Unexpected Finding: Subsidence Linked to Oil Production

While analyzing ground movement across the region, researchers noticed a striking signal in the La Brea area: about 30 centimeters of subsidence over 30 years. This movement is not linked to groundwater pumping but instead appears to be associated with oil and gas extraction.

The Los Angeles Basin contains a major underground oil reserve. Even though oil production has declined over time, large volumes of water are still extracted along with the remaining oil. The new satellite record provides the first clear, multi-decade confirmation that subsidence related to this activity has been ongoing and stable for decades.

What Comes Next for Research

The lead researcher, now an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Dallas, is currently working on a new project examining groundwater recharge during extreme wet periods, focusing on the unusually rainy 2022–23 season. This research will combine InSAR data with seismic measurements and hydrological models to better understand how aquifers respond when large amounts of water suddenly become available.

These efforts aim to improve predictions about how groundwater systems behave under increasingly unpredictable climate conditions—and how best to manage them without causing long-term harm.

A Broader Look at Groundwater and Subsidence

Ground subsidence caused by groundwater extraction is not unique to Los Angeles. It has been documented worldwide, from California’s Central Valley to cities in China, Mexico, and Indonesia. Once underground layers compact permanently, the lost storage space cannot be recovered, even if water levels rise again.

This is why identifying sustainable pumping limits is so critical. Tools like InSAR provide a powerful way to observe these changes directly, rather than relying solely on models or limited ground-based measurements.

What This Study Ultimately Shows

This research makes one thing clear: local groundwater is a valuable but fragile resource. The Hollywood Basin can support water supply needs, but only if pumping levels are aligned with the basin’s true physical limits. Satellite data now gives scientists and water managers a clearer way to see those limits—and to avoid crossing them.

As Southern California continues to adapt to climate uncertainty, studies like this highlight how advanced technology and long-term data can lead to smarter, more sustainable decisions about water.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.1029/2024WR039161