Satellite Observations Reveal Unexpected Tsunami Behavior After the Massive 2025 Kamchatka Earthquake

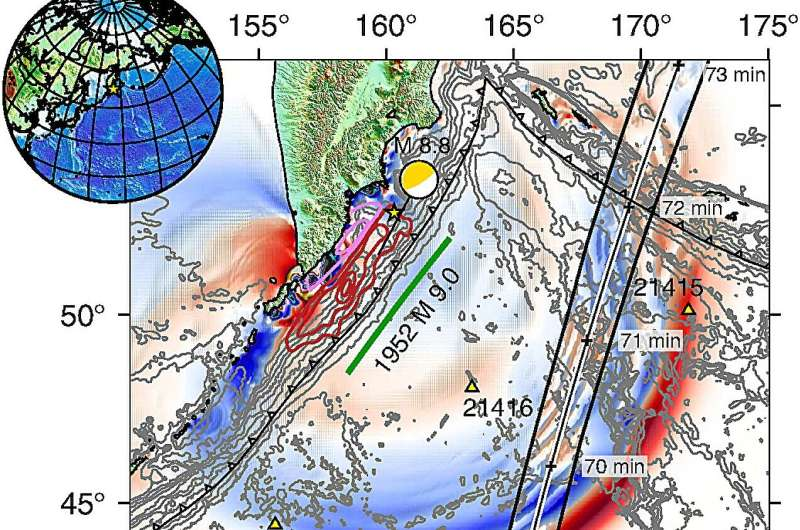

A powerful magnitude 8.8 earthquake struck off Russia’s Kamchatka Peninsula on 29 July 2025, triggering a Pacific-wide tsunami and offering scientists a rare opportunity to observe how such massive ocean waves behave in the real world. What made this event especially significant was that it was captured by the SWOT satellite, a cutting-edge space mission designed to measure ocean surface heights with unprecedented detail. The observations have challenged long-standing assumptions about how large tsunamis travel across the ocean and may lead to meaningful changes in tsunami modeling and forecasting.

The earthquake occurred along the Kuril–Kamchatka subduction zone, one of the most seismically active regions on Earth, where the Pacific Plate is forced beneath the Okhotsk Plate. With a magnitude of 8.8, the event ranks as the sixth-largest earthquake recorded globally since 1900. Earthquakes of this size are rare, and when they occur beneath the ocean, they often generate tsunamis capable of crossing entire ocean basins.

In this case, tsunami warnings were issued across the Pacific, continuing a legacy of regional preparedness that dates back to the devastating 1952 magnitude 9.0 Kamchatka earthquake, which played a key role in the creation of the international Pacific tsunami warning system.

A Satellite in the Right Place at the Right Time

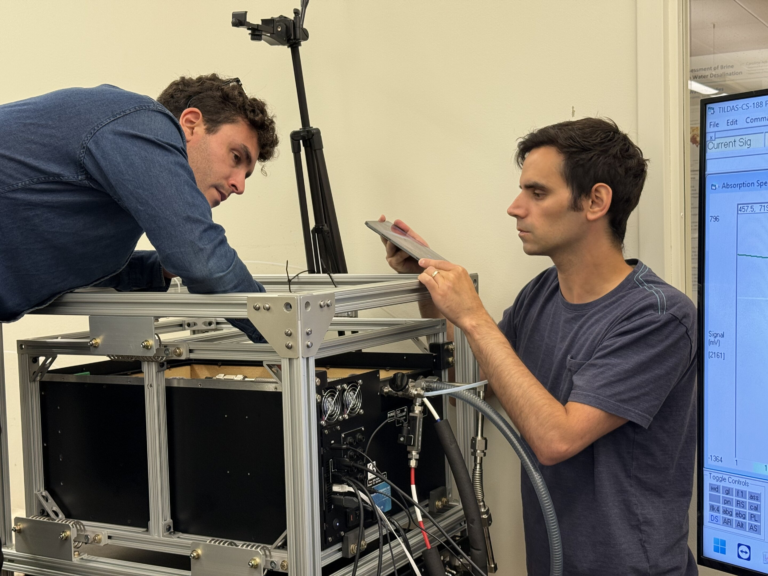

What sets the 2025 Kamchatka tsunami apart from previous events is the role played by the Surface Water and Ocean Topography (SWOT) satellite. Launched in December 2022 as a joint mission between NASA and France’s Centre National d’Études Spatiales (CNES), SWOT was built to provide the first global survey of Earth’s surface water, including oceans, lakes, rivers, and reservoirs.

Unlike older satellite altimeters that measure the ocean surface along a narrow line, SWOT can observe a swath up to about 120 kilometers wide. This wide coverage allows scientists to see far more of the ocean surface at once, capturing detailed patterns that were previously invisible.

Roughly 70 minutes after the earthquake, SWOT passed directly over the tsunami as it propagated across the Pacific. The satellite recorded high-resolution sea-surface height variations, providing the first-ever detailed, spaceborne view of a great subduction-zone tsunami.

Tsunami Waves Were More Complex Than Expected

For decades, scientists have treated large tsunamis as mostly non-dispersive waves. This means that, because their wavelengths are much longer than the depth of the ocean, the waves were thought to travel as a relatively clean, coherent front without breaking into multiple wave trains.

The SWOT data told a different story.

Instead of a single, smooth wave crest, the satellite observed a complex pattern of dispersing and scattering waves spreading across the ocean basin. Trailing waves followed the main crest, interacting with it and adding unexpected variability to the overall tsunami signal.

These observations suggest that dispersion plays a more important role in large tsunamis than previously believed. When researchers compared the satellite data to numerical simulations, they found that tsunami models that included dispersive effects matched the real-world observations far better than traditional models that ignored them.

This finding has important implications. If dispersion affects how tsunami energy evolves as it travels, it could influence arrival times, wave heights, and how energy is distributed when waves reach coastlines.

Deep-Ocean Buoys Help Refine the Earthquake Source

Satellite data alone was not the only key to understanding this event. Scientists also relied on measurements from DART buoys, part of the Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis system. These instruments sit on the ocean floor and measure subtle changes in water pressure caused by passing tsunami waves.

Data from three DART buoys in the tsunami’s path revealed discrepancies between observations and predictions based on earlier earthquake models. Specifically, some models predicted the tsunami would arrive earlier at one buoy and later at another than what was actually recorded.

To resolve this, researchers performed a detailed inversion analysis, combining tsunami observations with modeling to reassess the earthquake’s rupture characteristics. The results showed that the earthquake rupture extended farther south than previously estimated and had a total rupture length of approximately 400 kilometers, significantly longer than the 300 kilometers suggested by earlier models.

This revised source model helps explain the tsunami’s observed behavior and highlights the value of using tsunami data, not just seismic data, to understand large earthquakes.

Why Mixing Data Sources Matters

Since the 2011 magnitude 9.0 Tohoku-oki earthquake in Japan, scientists have increasingly recognized that tsunami measurements contain critical information about shallow slip near the trench, which is often poorly resolved by seismic data alone.

However, combining seismic models of the solid Earth with hydrodynamic models of ocean waves is technically challenging, and tsunami data is still not routinely used in earthquake inversions. The Kamchatka event provides another clear example of why this integration is essential.

By merging SWOT satellite observations, DART buoy data, and numerical tsunami simulations, researchers were able to build a more accurate picture of both the earthquake source and the tsunami it generated.

Broader Implications for Tsunami Forecasting

The findings from the 2025 Kamchatka tsunami could have long-term impacts on how tsunamis are modeled and forecast. If large tsunamis routinely carry more dispersive energy than previously assumed, current forecasting systems may be missing important details that affect coastal hazard assessments.

While the tsunami from this event caused less damage than initially feared in many regions, the new insights raise important questions. Could dispersive effects amplify or reduce tsunami impact in certain coastal geometries? Could trailing waves significantly alter flooding patterns in bays and harbors?

Answering these questions will require further study, but the Kamchatka event demonstrates that satellite-based ocean observations have the potential to become a powerful tool for near-real-time tsunami monitoring and forecasting in the future.

Understanding Subduction Zone Earthquakes

Subduction zones like the Kuril–Kamchatka margin are responsible for the largest earthquakes and tsunamis on Earth. When stress builds up over centuries and is suddenly released, enormous sections of the seafloor can move vertically, displacing vast volumes of water.

The 1952 Kamchatka earthquake remains one of the most significant examples, and the 2025 event reinforces the region’s status as a major seismic and tsunami hazard. Continuous monitoring using satellites, ocean buoys, and seismic networks is essential for improving warning systems and reducing risk for coastal communities.

A New Era of Ocean Observation

The successful capture of the Kamchatka tsunami marks a milestone for the SWOT mission. Originally designed to study water resources and ocean circulation, SWOT has now proven its value for extreme geophysical events.

As satellite technology continues to advance, scientists hope that observations like these will eventually support real-time tsunami detection, complementing existing warning systems and providing richer information about how tsunamis evolve across the open ocean.

For now, the 2025 Kamchatka earthquake stands as a powerful reminder that even well-studied natural phenomena can still surprise us—and that new tools can fundamentally reshape our understanding of the planet.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1785/0320250037