Scientists Discover That Deep Ocean Carbon Fixation Works Very Differently Than We Thought

For years, scientists have believed they had a fairly solid understanding of how carbon is locked away in the deep ocean. A new study led by researchers at the University of California, Santa Barbara, now shows that some of those assumptions were incomplete. The findings reshape how scientists think about carbon fixation in the dark ocean, revealing that the microbes responsible are not quite who we thought they were.

The research, published in Nature Geoscience, addresses a long-standing mystery in ocean science: how large amounts of dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) appear to be fixed in ocean depths where sunlight does not reach, even when known energy sources seem insufficient to support that process.

Why the Deep Ocean Matters for the Climate

The ocean is the planet’s largest carbon sink, absorbing roughly one-third of human carbon dioxide emissions. This absorption plays a major role in regulating global temperatures and slowing climate change. However, carbon does not simply stay at the surface. For the ocean to store carbon long-term, it must be transported and transformed in deeper layers.

Understanding how carbon moves from the atmosphere to the deep ocean is therefore critical. Microorganisms play a central role in this process, converting inorganic carbon into organic forms that can sink or circulate through the marine food web.

The Traditional View of Carbon Fixation in the Ocean

In surface waters, carbon fixation is dominated by phytoplankton, microscopic organisms that use sunlight to convert carbon dioxide into organic matter through photosynthesis. This process is well studied and widely accepted.

Below the sunlit zone, however, conditions are very different. In these dark ocean layers, photosynthesis is impossible. Scientists have long believed that carbon fixation there is driven mainly by ammonia-oxidizing archaea. These microbes do not rely on sunlight. Instead, they gain energy by oxidizing ammonia, a nitrogen-containing compound, and use that energy to fix inorganic carbon.

Based on this idea, ammonia-oxidizing archaea were thought to be the primary engines of non-photosynthetic carbon fixation in the deep sea.

A Persistent Energy Budget Problem

As researchers began measuring carbon fixation rates directly in deep waters, something did not add up. The amount of carbon being fixed appeared to be too high compared to the available nitrogen-based energy sources.

In simple terms, the microbes seemed to be doing more carbon fixation than their known energy supply should allow. This mismatch became known as an energy budget discrepancy, and it raised doubts about whether ammonia-oxidizing archaea could truly account for all the observed carbon fixation.

Researchers, including microbial oceanographer Alyson Santoro and lead author Barbara Bayer, spent years trying to resolve this issue. One possibility was that ammonia-oxidizing archaea were more efficient than assumed, needing less nitrogen to fix carbon. However, previous studies showed that this explanation did not fully solve the problem.

A New Experimental Approach

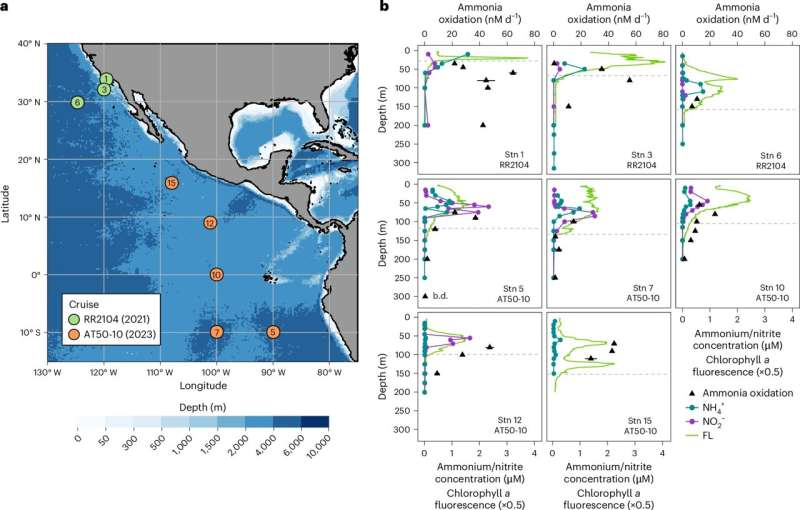

Instead of asking whether ammonia-oxidizing archaea were more efficient, the research team took a different angle. They asked a more direct question: how much of deep-ocean carbon fixation is actually done by these organisms?

To find out, the team designed an experiment that selectively inhibited ammonia-oxidizing microbes. They used a chemical called phenylacetylene, which specifically blocks the enzyme ammonia oxidizers use to generate energy. Importantly, the inhibitor was carefully tested to ensure it did not interfere with other microbial processes in the water.

The logic was straightforward. If ammonia-oxidizing archaea were responsible for most carbon fixation at depth, then shutting them down should cause carbon fixation rates to drop dramatically.

That is not what happened.

A Surprising Result from the Deep Ocean

When ammonia oxidizers were inhibited, carbon fixation rates decreased only slightly, far less than expected. Even in regions where these archaea were abundant, their removal could not explain the majority of carbon fixation taking place.

This result strongly suggested that other microbes were playing a much larger role than previously believed.

By analyzing the data across different depths and regions, the researchers found that ammonia-oxidizing archaea contributed only a minor fraction of total deep-ocean inorganic carbon fixation. In some depth ranges, their contribution was higher, but overall they could not account for the full picture.

The Unexpected Role of Heterotrophic Microbes

So who is doing the rest of the carbon fixing?

The study points to heterotrophic microbes, organisms traditionally thought to rely almost entirely on consuming organic carbon produced by others. These microbes are abundant in the deep ocean, feeding on the remains of dead phytoplankton, sinking particles, and dissolved organic matter.

What this research shows is that many of these heterotrophs also take up inorganic carbon and incorporate it into their cells. In other words, they are not just recycling carbon — they are actively fixing it.

This finding is particularly interesting because heterotrophic carbon fixation has long been considered theoretically possible, but it was rarely quantified at meaningful scales. This study provides one of the clearest estimates yet of how significant that contribution can be.

What This Means for the Deep-Ocean Food Web

These results reshape our understanding of the base of the deep-ocean food web. Carbon fixation is not limited to a narrow group of specialized autotrophs. Instead, it appears to be distributed across a broader range of microbial life.

This mixed strategy — consuming organic carbon while also fixing inorganic carbon — suggests that deep-ocean microbes are more metabolically flexible than previously assumed. That flexibility may help them survive in environments where energy and nutrients are scarce and unevenly distributed.

It also means that carbon cycling in the deep ocean is likely more complex than current models account for.

Implications for Global Carbon Models

Accurate climate models depend on realistic representations of how carbon moves through Earth’s systems. If deep-ocean carbon fixation is driven largely by heterotrophic microbes rather than ammonia oxidizers, then estimates of carbon sequestration efficiency may need to be revised.

This research also helps resolve the long-standing nitrogen-energy mismatch. If fewer microbes rely solely on ammonia oxidation, the energy budget finally makes sense.

Connections to Other Ocean Cycles

The study opens the door to new questions about how the carbon cycle interacts with other elemental cycles, including nitrogen, iron, and copper. These elements influence microbial metabolism, enzyme function, and nutrient availability.

Understanding these connections will be crucial for predicting how the ocean responds to warming, acidification, and changing nutrient inputs under future climate conditions.

What Scientists Want to Study Next

One major unanswered question is what happens after microbes fix carbon. Once inorganic carbon becomes part of microbial cells, it can be released as organic compounds, transferred through the food web, or stored in the deep ocean for long periods.

Researchers now want to identify which organic molecules are released by these microbes and how they support other deep-sea organisms. These processes determine whether carbon remains locked away or eventually returns to the atmosphere.

Why This Study Matters

This research fundamentally changes how scientists view carbon fixation in the deep ocean. It shows that carbon storage is not controlled by a single group of microbes, but by a diverse community with overlapping roles.

By clarifying who is responsible for deep-ocean carbon fixation, the study strengthens our understanding of one of Earth’s most important climate buffers. It also highlights how much remains to be learned about the hidden biological processes operating far below the ocean surface.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41561-025-01798-x