Scientists Finally Show How Powerful Tropical Cyclones Influence the Ocean Carbon Cycle

For decades, scientists have known that tropical cyclones do much more than cause destruction on land. These massive storms also churn the oceans, redistribute heat, and disturb marine ecosystems. Now, for the first time, researchers have been able to capture the effects of extremely intense tropical cyclones on the ocean carbon cycle using a global, high-resolution Earth system model. The findings reveal a complex chain of physical and biological processes that affect how the ocean releases and absorbs carbon dioxide, as well as how marine life responds in the aftermath of these storms.

The new study was carried out by scientists from the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology and the University of Hamburg, and the results were published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). What makes this work stand out is not just what the researchers discovered, but how they discovered it.

Why tropical cyclones matter for the ocean carbon cycle

Tropical cyclones are among the most powerful weather systems on Earth. With extreme wind speeds, heavy rainfall, and towering waves, they dramatically disturb the ocean surface. When these storms pass over the sea, they force intense mixing between surface waters and deeper layers. This mixing plays a crucial role in how heat, nutrients, and carbon dioxide (CO₂) move between the ocean and the atmosphere.

Until now, most Earth system models were simply too coarse to represent these storms accurately. Traditional global models typically use grid spacing of 100 to 200 kilometers, which smooths out the fine-scale features of intense cyclones. As a result, the strongest storms — especially category-4 and category-5 hurricanes — were either poorly represented or missed entirely.

This limitation meant scientists could not fully explore how these storms influence the global carbon cycle, even though observations hinted that the effects could be significant.

A model that finally captures extreme hurricanes

To overcome this problem, the research team used the ICON Earth system model, which operates at a much finer horizontal resolution of 5 kilometers. At this scale, the model can realistically simulate storm dynamics, ocean eddies, and air–sea interactions that were previously out of reach.

Crucially, the model also includes the HAMOCC ocean biogeochemistry component, which tracks nutrients, plankton growth, and carbon flows within the ocean. This combination allowed the scientists to examine not just the physical impact of storms, but also their biogeochemical consequences.

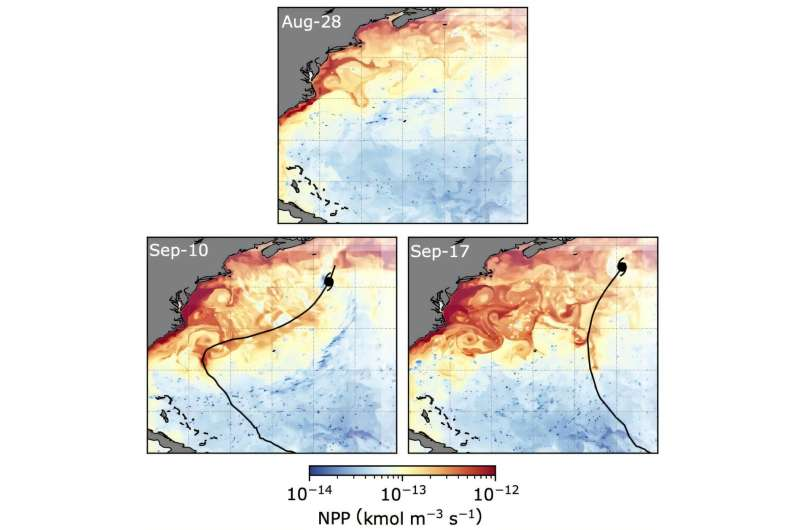

Within a one-year global simulation, the researchers identified two category-4 hurricanes that formed in the North Atlantic in September 2020, appearing roughly one week apart. Both storms had wind speeds exceeding 200 kilometers per hour, making them ideal test cases for studying extreme cyclone behavior.

Immediate CO₂ release followed by weeks of uptake

One of the most striking findings involves how hurricanes affect the exchange of carbon dioxide between the ocean and the atmosphere.

As the hurricanes passed over the ocean, their violent winds caused intense surface mixing. This process brought CO₂-rich water from below up to the surface, where it could escape into the atmosphere. During the storms, the release of CO₂ was 20 to 40 times stronger than what occurs under normal weather conditions.

However, this was only part of the story.

After the storms moved on, the ocean surface remained significantly cooler for several weeks. Cooler water can dissolve more carbon dioxide, and this cooling enhanced the uptake of atmospheric CO₂ back into the ocean. When the researchers accounted for both the short-term release and the longer-term absorption, the net effect turned out to be a small overall uptake of CO₂.

This balance between opposing processes highlights how complex and dynamic the ocean carbon cycle becomes during extreme weather events.

Hurricanes trigger massive phytoplankton blooms

Beyond carbon exchange, the storms also had a dramatic impact on marine life — particularly phytoplankton, the microscopic organisms that form the base of the ocean food web.

The intense mixing caused by the hurricanes transported nutrients from deeper waters up into the sunlit surface layer. With an abundance of nutrients suddenly available, phytoplankton growth surged. According to the model results, phytoplankton production increased by a factor of ten following the storms.

These blooms were not short-lived. They persisted for several weeks and extended far beyond the immediate storm tracks. Ocean currents — some of which were strengthened by the hurricanes themselves — spread the phytoplankton biomass across large regions of the western North Atlantic.

This finding is important because phytoplankton play a central role in the biological carbon pump, the process by which carbon is transferred from the surface ocean to deeper layers.

More organic carbon sinks into the deep ocean

As phytoplankton grow and eventually die, some of their organic material sinks toward the ocean floor. The study showed that hurricane-induced blooms led to an increase in the amount of organic carbon exported to deeper waters.

This sinking carbon contributes to long-term carbon storage, effectively removing CO₂ from the atmosphere for years, decades, or even longer. While the net carbon uptake from individual storms may be modest, the cumulative effect of many intense cyclones could be meaningful on regional or global scales.

Why this research is a big step forward

Scientists have observed individual pieces of this puzzle before, such as storm-induced cooling or post-hurricane plankton blooms. What sets this study apart is that it connects all of these processes within a single global framework.

By resolving tropical cyclones at kilometer-scale resolution, the researchers were able to trace how physical disturbances cascade into biogeochemical responses, from CO₂ exchange to nutrient mixing to carbon sequestration. This kind of integrated view is essential for improving future climate projections.

As the climate warms, scientists expect changes in storm intensity, frequency, and behavior. Understanding how tropical cyclones interact with the carbon cycle will help clarify whether these storms amplify or dampen climate change over time.

Expanding the view beyond the tropics

The researchers see this work as a starting point rather than a final answer. Their next steps include studying other kilometer-scale processes, such as interactions between storms and ocean eddies, which can further influence nutrient and carbon transport.

They also plan to explore similar mechanisms in polar regions, where intense storms and ocean mixing may play an underappreciated role in regional carbon dynamics.

A broader look at tropical cyclones and climate

Tropical cyclones are often discussed only in terms of their destructive impacts on human communities. This research serves as a reminder that these storms are also powerful agents of change in the Earth system. They reshape ocean structure, alter ecosystems, and influence how carbon moves between the ocean and atmosphere.

Thanks to advances in high-resolution modeling, scientists are now beginning to see the full picture — and it is far more complex and fascinating than previously imagined.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2506103122