Scientists Map Key Oceanic Unknowns in Climate Interventions as Oceans Face Growing Climate Stress

As the planet continues to warm, Earth’s oceans are undergoing some of the most dramatic and concerning changes seen anywhere in the climate system. Rising temperatures, increasing acidity, and declining oxygen levels are already reshaping marine ecosystems, threatening biodiversity, food webs, and the global fisheries that millions of people depend on for food and livelihoods. While scientists broadly agree that cutting greenhouse gas emissions remains the most critical priority, current global efforts are not moving fast enough to keep warming within the 1.5 to 2 degrees Celsius limits outlined in the Paris Agreement.

Against this backdrop, researchers are increasingly exploring climate intervention strategies—sometimes referred to as geoengineering—as potential additions to emissions reductions. A major new scientific review now takes a close look at what these interventions could mean for the oceans, and more importantly, how much remains unknown.

A team of 26 scientists from around the world has published a comprehensive review in the journal Reviews of Geophysics that examines how various climate intervention approaches might affect marine ecosystems. The paper, led by Kelsey E. Roberts, a visiting scholar in Cornell University’s Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, is titled Potential Impacts of Climate Interventions on Marine Ecosystems. Its goal is not to advocate for deploying these technologies, but to clearly map out what scientists currently understand—and where the biggest gaps in knowledge lie.

The central message of the review is clear: oceans will be on the front lines of any large-scale climate intervention, yet the scientific community still lacks a solid understanding of how these actions could ripple through marine systems.

Understanding Climate Intervention Strategies

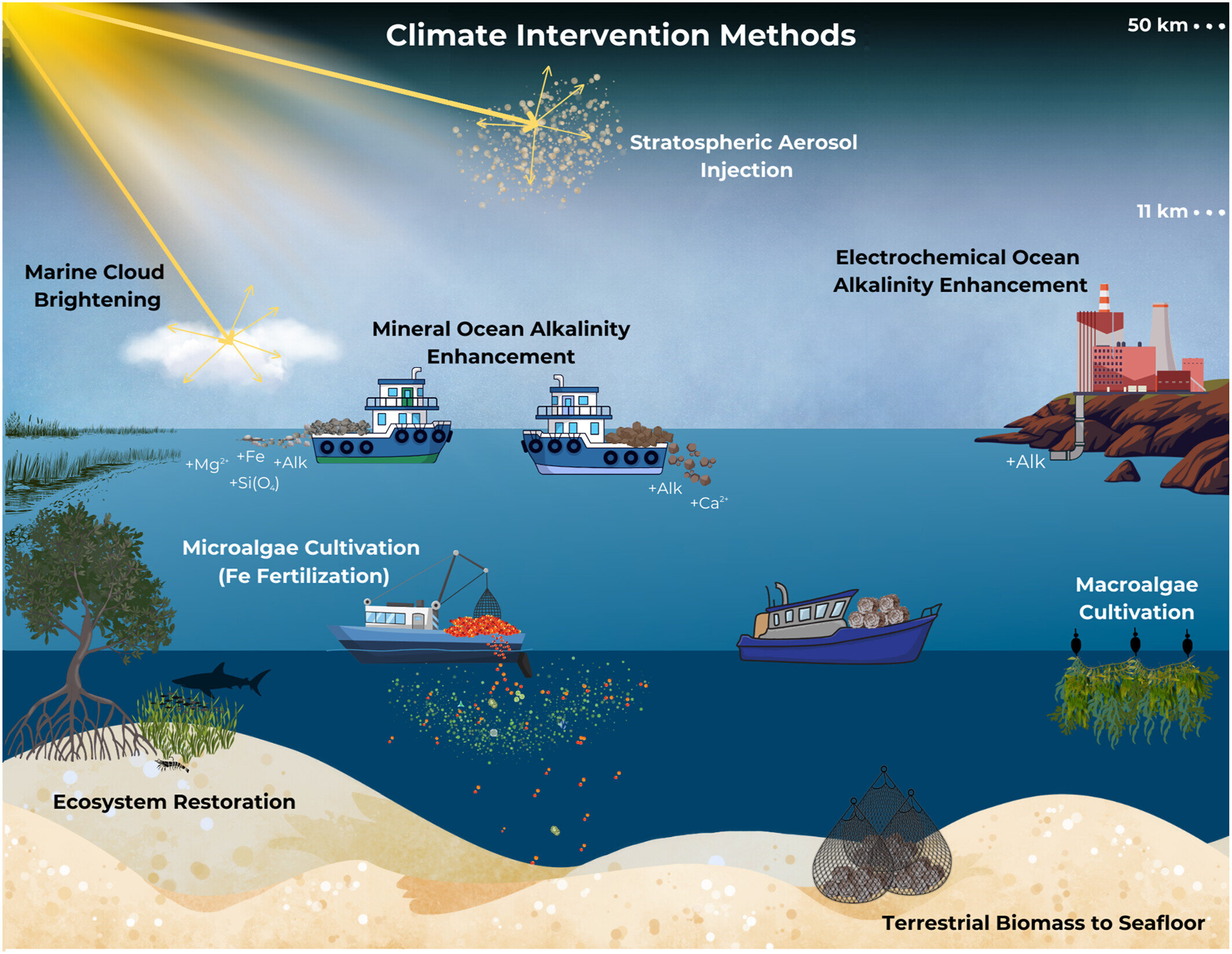

The review focuses on two broad categories of climate interventions that are most frequently discussed in scientific and policy circles: carbon dioxide removal (CDR) and solar radiation modification (SRM).

Carbon dioxide removal strategies aim to pull CO₂ out of the atmosphere and store it for long periods of time. Many proposed CDR approaches rely heavily on the oceans, which already absorb roughly a quarter of human-produced carbon dioxide emissions each year.

Researchers are investigating several ocean-based CDR methods. These include fertilizing certain regions of the ocean with nutrients to stimulate phytoplankton growth, since phytoplankton absorb carbon dioxide during photosynthesis. Other approaches involve large-scale seaweed farming, sinking plant material grown on land into deep ocean waters, or enhancing ocean alkalinity by adding alkaline substances to seawater to increase its ability to absorb CO₂.

If these methods work as intended, they could increase the amount of carbon stored in the oceans. However, the review emphasizes that any increase in ocean carbon storage comes with trade-offs. Altering nutrient levels or chemical balances in seawater could disrupt marine ecosystems, change species composition, and affect food webs in ways that are difficult to predict.

Solar Radiation Modification and Its Ocean Implications

The second major category, solar radiation modification, takes a very different approach. Instead of addressing greenhouse gases directly, SRM aims to cool the planet by reflecting some sunlight back into space. Two commonly discussed SRM techniques are stratospheric aerosol injection, which involves releasing reflective particles high in the atmosphere, and marine cloud brightening, which seeks to make low-lying ocean clouds more reflective.

SRM methods could, in theory, reduce global temperatures relatively quickly. However, the review highlights substantial risks and uncertainties, especially for the oceans. Changes in sunlight, temperature gradients, and atmospheric circulation could influence rainfall patterns, ocean currents, and marine productivity. Another major concern is the possibility of rapid warming if SRM were ever stopped abruptly, a phenomenon sometimes called “termination shock.”

What makes SRM particularly complex is that while it may lower surface temperatures, it does nothing to address ocean acidification, which is driven by elevated carbon dioxide levels rather than temperature alone.

Major Knowledge Gaps and Ecological Risks

One of the most important contributions of the review is its systematic identification of what scientists still don’t know. While some effects of climate interventions can be modeled, many ocean processes are deeply interconnected and vary across regions.

The authors point to especially large gaps in understanding how interventions might affect marine food webs and fisheries. Small changes at the base of the food chain, such as shifts in phytoplankton communities, can cascade upward, influencing fish populations and ecosystem stability. These impacts could have direct consequences for coastal communities and global seafood supplies.

The review also stresses that the effects of climate interventions depend heavily on how, where, and at what scale they are implemented. A localized experiment might produce very different outcomes compared to a global deployment. Timing matters too, as interventions introduced into an already stressed ocean could amplify existing problems rather than alleviate them.

Importantly, the researchers make it clear that climate interventions are not a substitute for emissions reductions. At best, they could potentially reduce some climate impacts if used cautiously and alongside aggressive efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions. At worst, poorly understood interventions could create new environmental problems.

Why the Oceans Matter So Much

Oceans play a central role in regulating Earth’s climate. They absorb heat, store carbon, and support complex ecosystems that influence atmospheric processes. Because of this, any attempt to deliberately alter the climate will almost inevitably involve the oceans in some way.

What makes marine systems particularly challenging is their sheer scale and complexity. Physical, chemical, and biological processes interact across vast distances and long time scales. A change in one part of the ocean can influence conditions thousands of kilometers away. This interconnectedness is why the authors argue for much more interdisciplinary research, combining oceanography, ecology, climate science, and social sciences.

The Need for Responsible Research

Rather than promoting or dismissing climate interventions outright, the review takes a careful and measured stance. One of the co-authors, Daniele Visioni, an assistant professor at Cornell and a faculty fellow at the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability, has emphasized the importance of expanding research so future decisions are informed by solid evidence rather than speculation.

The authors hope their work will serve as a roadmap for future research, helping scientists prioritize the most urgent questions and design studies that can reduce uncertainty. This includes improving models, conducting controlled field experiments where appropriate, and better integrating ecological impacts into climate assessments.

Additional Context: Climate Interventions in the Broader Debate

Climate interventions remain one of the most controversial topics in climate science. Supporters argue that given the pace of warming, it would be irresponsible not to study potential tools that might reduce harm. Critics worry that focusing on these approaches could distract from emissions cuts or lead to unintended consequences if deployed prematurely.

What this new review makes clear is that the ocean dimension of climate interventions has not received enough attention, despite the fact that marine systems are both highly vulnerable and critically important. Any future discussion about deploying such technologies will need to grapple seriously with ocean impacts.

For now, the takeaway is one of cautious curiosity. Climate interventions may offer possibilities, but they also raise profound scientific, ethical, and environmental questions. Mapping what we know—and what we don’t—is a necessary step before any informed decisions can be made.

Research Paper Reference:

https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1029/2024RG000876