Signs of Ancient Life Turn Up in an Unexpected Place Deep Beneath the Seafloor

Scientists studying ancient rocks in Morocco have uncovered surprising evidence of microbial life in a place where it was never expected to exist. The discovery challenges long-standing assumptions about where and how early life left traces in the geological record, and it opens up entirely new environments for scientists searching for ancient biological activity.

The finding comes from the Dadès Valley in the Central High Atlas Mountains of Morocco, where rocks that are now exposed on land were once buried deep beneath the ocean. While walking through this rugged landscape, Dr. Rowan Martindale, a paleoecologist and geobiologist at the University of Texas at Austin, noticed unusual textures preserved on the surfaces of ancient sedimentary rocks. What initially looked like ordinary ripples soon revealed something much more significant.

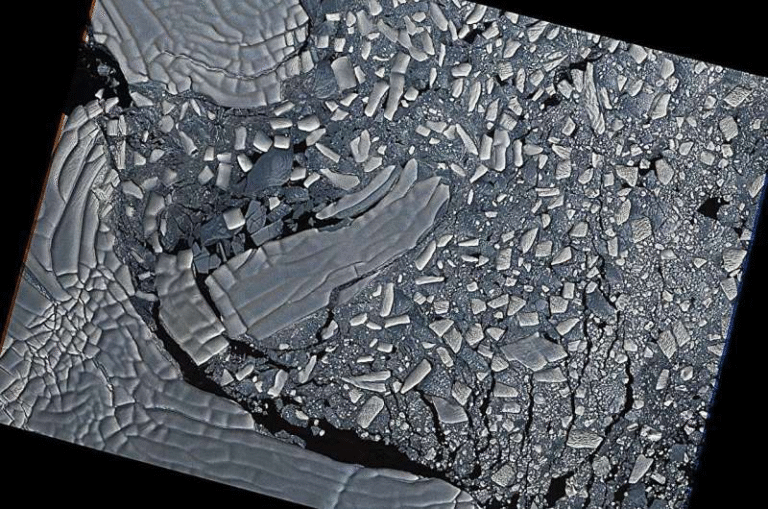

These rocks date back roughly 180 million years, to the Early Jurassic period. At that time, the region was submerged beneath a deep marine environment, far below the reach of sunlight. Yet the textures Martindale observed resembled wrinkle structures, features that are typically linked to microbial mats formed by living organisms.

What Are Wrinkle Structures and Why They Matter

Wrinkle structures are millimeter- to centimeter-scale ridges, pits, and folds preserved on sediment surfaces. They form when microbial communities, often algae or bacteria, grow as cohesive mats on loose sediment. As water flows over or through these mats, they deform in distinctive ways, leaving behind textured patterns once the sediment hardens into rock.

These structures are considered important indicators of early life, especially in very old rocks. However, they are rare in rocks younger than about 540 million years, after animals evolved in large numbers and began disturbing the seafloor. Burrowing, grazing, and other animal activities usually destroy delicate microbial textures before they can be preserved.

In modern environments, wrinkle structures are most commonly found in shallow, sunlit waters, such as tidal flats, where photosynthetic microbes thrive. That is why their presence in deep-water rocks immediately raised questions.

Why the Discovery Was So Unexpected

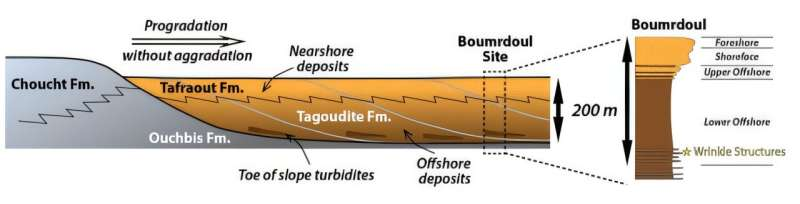

The rocks containing these wrinkle structures are turbidites, sediments deposited by underwater debris flows. Turbidites form when dense, sediment-laden currents rush downslope into deep ocean basins, depositing layers of sand, silt, and mud. The specific turbidites in the Dadès Valley were laid down at depths of at least 180 meters below the ocean surface, well beneath the photic zone where sunlight penetrates.

This depth alone makes the discovery surprising. Even more puzzling is the age of the rocks. By 180 million years ago, animals were abundant and actively reworking the seafloor, which should have erased any microbial textures long before they could fossilize. Previous claims of wrinkle structures in deep-marine turbidites have often been contested or dismissed, making this find particularly controversial at first glance.

Recognizing the implications, Martindale and her colleagues set out to verify every aspect of the discovery.

Confirming the Biological Origin

The research team carefully examined the geological context to confirm that the sediments were indeed turbidites and not misidentified shallow-water deposits. Stratigraphic analysis showed a clear vertical succession of deep-water facies, including toe-of-slope turbidites at the base and shallower deposits higher up. The wrinkle structures were found in the deepest portions of this sequence.

Chemical analysis added another key piece of evidence. Sediment layers just beneath the wrinkled surfaces showed elevated carbon levels, a strong indicator of biological material. This carbon enrichment is consistent with the presence of microbial mats rather than purely physical sedimentary processes.

To explain how microbes could survive without sunlight, the researchers turned to modern analogs. Observations from remotely operated submersibles exploring today’s deep oceans show that microbial mats can thrive far below the photic zone. These communities rely on chemosynthesis, obtaining energy from chemical reactions instead of photosynthesis.

How Chemosynthetic Microbes Shaped the Seafloor

Chemosynthetic microbes use chemical compounds such as sulfides or methane as energy sources. In deep-sea environments, these compounds are often abundant, especially where organic matter accumulates. The researchers propose that ancient turbidite flows delivered nutrients and organic material to the deep seafloor, creating low-oxygen conditions ideal for chemosynthetic life.

During calm periods between debris flows, microbial mats formed on the sediment surface. As these mats interacted with gentle currents or compacted under their own weight, they developed the distinctive wrinkle textures. In most cases, subsequent turbidite flows would have eroded the mats away. However, on rare occasions, the mats were buried and preserved, locking their textures into the rock record.

This mechanism explains how such fragile features could survive in a dynamic deep-marine environment.

Broader Implications for Earth’s History

The discovery has significant implications for how scientists interpret ancient rocks. For decades, wrinkle structures were almost exclusively linked to photosynthetic microbial communities in shallow water. This study shows that similar structures can form in deep-water settings through entirely different biological pathways.

By recognizing that chemosynthetic microbes can produce wrinkle structures, geologists may need to re-evaluate sedimentary environments previously dismissed as unlikely to preserve biological evidence. Deep-marine turbidites, once considered poor candidates for life signatures, could hold untapped records of microbial ecosystems.

This also affects how scientists search for early life on Earth and potentially on other planets. Environments without sunlight, once seen as barren, may actually be rich in chemical energy capable of supporting life.

Extra Context: Turbidites and the Deep Sea

Turbidites are among the most widespread sedimentary deposits on Earth. They form vast layers across ocean basins and are commonly exposed in mountain belts where ancient seafloor has been uplifted. Because they accumulate rapidly and repeatedly, turbidites can preserve high-resolution snapshots of ancient environments.

The deep sea itself is one of Earth’s largest habitats, yet it remains poorly understood in both modern and ancient contexts. Chemosynthetic ecosystems today, such as those found near hydrothermal vents, demonstrate that life does not require sunlight to flourish. This discovery shows that similar principles applied hundreds of millions of years ago, even in settings not directly associated with vents.

Looking Ahead

Martindale and her team plan to conduct laboratory experiments to better understand how wrinkle structures form under deep-water conditions. They also hope the study encourages other researchers to re-examine turbidite sequences worldwide for overlooked signs of microbial life.

Wrinkle structures are more than just interesting textures. They are windows into the early evolution of life, recording how microbes interacted with their environments long before complex ecosystems dominated the planet. Expanding the range of settings where scientists look for these features could significantly reshape our understanding of Earth’s biological past.

Research paper: Chemosynthetic microbial communities formed wrinkle structures in ancient turbidites, Geology (2025). https://doi.org/10.1130/G53617.1