Storms Reveal How Marine Snow Controls the Flow of Carbon Into the Deep Ocean

Scientists have long known that the ocean plays a massive role in regulating Earth’s climate, but exactly how carbon moves from the surface into the deep sea has remained difficult to pin down. A new study led by researchers from the University of California, Santa Barbara sheds fresh light on this process by closely examining marine snow—tiny clumps of organic material that act as one of the ocean’s main carbon delivery systems. The research shows that storms dramatically influence how efficiently carbon sinks, revealing a far more dynamic and complex system than previously understood.

This work is the result of an ambitious international expedition carried out during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, when scientists faced not only scientific challenges but also unprecedented logistical hurdles. Despite everything stacked against them, the team gathered some of the most detailed real-world observations ever made of the ocean’s biological carbon pump, offering insights that could significantly improve climate models.

What Marine Snow Is and Why It Matters

Marine snow refers to fluffy, snow-like particles made up of dead phytoplankton, fecal pellets, mucus, bacteria, and other organic debris. These particles form in the upper ocean and slowly drift downward, transporting carbon away from the surface and into the deep sea.

This process is central to the ocean’s biological carbon pump, one of the planet’s most important climate regulators. Phytoplankton at the ocean’s surface use sunlight to convert carbon dioxide into organic matter through photosynthesis. Every year, they fix roughly 55 to 60 billion metric tons of carbon. About 15% of that carbon eventually leaves the surface ocean and sinks into deeper layers, where it can remain locked away for months, centuries, or even millennia.

Marine snow plays an outsized role in this export. Individual phytoplankton cells sink very slowly—often just a meter per day. In contrast, marine snow aggregates can sink at speeds of up to 100 meters per day, making them an efficient vehicle for long-term carbon storage.

The EXPORTS Mission and Its Goals

The study is part of NASA’s EXPORTS program, short for Export Processes in the Ocean from RemoTe Sensing. The mission was designed to bridge a critical gap between satellite observations of ocean productivity and what actually happens to that organic carbon once it leaves the surface.

Satellites can measure how much carbon phytoplankton produce, but they cannot see what happens beneath the surface. EXPORTS was created to answer questions such as: How much of that carbon sinks? How fast does it sink? And what processes control its fate?

The North Atlantic expedition described in this study took place in spring 2021, following a highly successful North Pacific campaign in 2018. The Atlantic mission involved three advanced research vessels—R/V Sarmiento de Gamboa, RRS Discovery, and RRS James Cook—and scientists from around 40 institutions across multiple countries.

Research at Sea During a Pandemic

Conducting a multinational research cruise during COVID-19 was an enormous challenge. The original launch window in 2020 had to be postponed, grants were nearing expiration, and safety protocols had to be coordinated across countries with different public health rules.

Scientists and crew members underwent vaccinations, quarantines, and frequent testing. Ships that had been idle for long periods required recommissioning. Despite all of this, the expedition went forward without a single onboard COVID case—a remarkable achievement that later earned NASA’s project office an Administrator’s Group Achievement Award.

When Storms Shake the Ocean’s Carbon System

Once at sea, the team encountered another obstacle: four major storms with wind speeds exceeding 50 knots and waves rising more than 20 feet. While these storms made the work physically demanding, they turned out to be scientifically invaluable.

The researchers discovered that storms act like a giant blender for marine snow. Turbulence breaks large aggregates into smaller fragments. Smaller particles sink much more slowly, temporarily reducing the amount of carbon reaching deeper waters.

However, the story does not end there. Storms also deepen the ocean’s mixed layer, the upper region where turbulence keeps water well mixed. When conditions calm, the mixed layer becomes shallower again. This leaves behind a zone beneath it filled with shredded organic particles.

In this calmer environment, particles can re-aggregate into new marine snow, now safely below surface turbulence. A few days after each storm passed, researchers observed pulses of sinking marine snow, showing that storms can both delay and ultimately enhance carbon export.

These are among the first direct field observations linking ocean turbulence, particle breakup, re-aggregation, and sinking carbon flux in the real ocean.

Confirming Lab Results in the Open Ocean

For decades, much of what scientists knew about marine snow behavior came from laboratory experiments. There was always uncertainty about how well these controlled conditions reflected the real ocean.

In this case, the field data closely matched classic laboratory findings from earlier work on marine snow formation and breakup. This rare agreement between lab and ocean observations strengthens confidence in how scientists model particle dynamics.

What Happens to Marine Snow Below the Surface

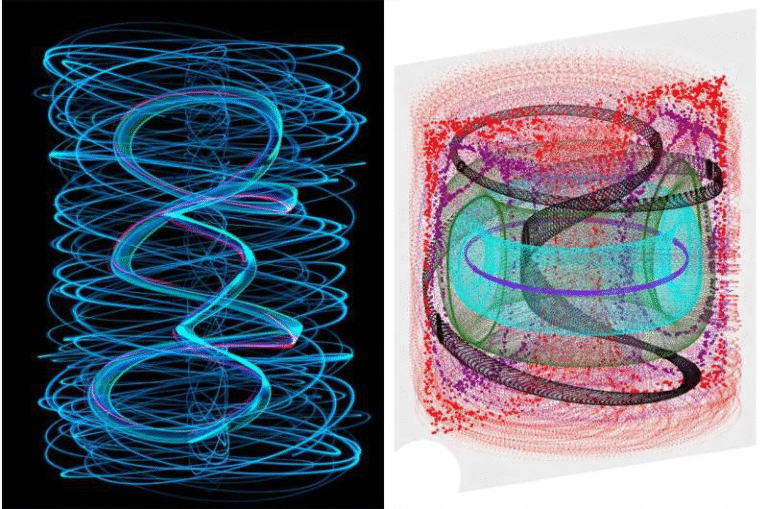

The team also tracked marine snow as it sank to depths between 200 and 500 meters. Over the course of the month-long study, the number of particles smaller than 0.5 millimeters roughly doubled.

These small particles could not have formed by sinking alone, which pointed to the breakdown of larger aggregates. Importantly, turbulence at these depths is minimal, ruling out physical mixing as the cause.

Instead, the researchers found that biological processes were responsible. Large particles were breaking down at a rate of about 12% per day, largely due to grazing and consumption by living organisms.

Zooplankton Play a Bigger Role Than Expected

One of the most striking findings involves zooplankton, the small drifting animals that feed on organic matter. While microbes were expected to dominate marine snow degradation, measurements showed that microbes accounted for less than half of the observed consumption.

Zooplankton interactions with marine snow—biting, grazing, and fragmenting particles—appear to be responsible for most of the breakdown. This process had been recognized before but had never been quantified so clearly in the open ocean.

Current Earth system models largely overlook this role, meaning carbon flux predictions may be significantly off. Incorporating zooplankton behavior could dramatically improve how scientists estimate how much carbon the ocean actually stores.

Why These Findings Matter for Climate Science

Marine snow may seem insignificant on its own, but across the vast scale of the ocean, small changes in particle behavior can lead to large errors in carbon cycle predictions. This study highlights why carbon flux is so difficult to model accurately.

By revealing how storms, turbulence, aggregation, and biology interact, the research provides a clearer framework for understanding carbon sequestration in the ocean. These insights will feed directly into improved climate and Earth system models.

The next phase of the EXPORTS mission is already underway, focused on integrating these observations into predictive tools. Researchers from around the world plan to meet in Glasgow in March 2026 to push this work forward.

Research Paper Reference

Assessing Marine Snow Dynamics During the Demise of the North Atlantic Spring Bloom Using In Situ Particle Imagery

Global Biogeochemical Cycles (2025)

https://doi.org/10.1029/2025GB008676