Study Separates Human and Hydrological Causes of Nitrogen Loss in the Mississippi Basin

Scientists at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign have taken an important step toward untangling one of the most persistent environmental challenges in the United States: excess nitrogen flowing through rivers and into downstream ecosystems. Their new research shows, for the first time at this scale, how human activities and hydrological variability independently contribute to nitrogen loss in the Upper Mississippi River Basin. This distinction matters because nitrogen pollution affects drinking water quality, fuels massive low-oxygen “dead zones” in the Gulf of Mexico, and complicates efforts to design effective nutrient reduction policies.

The study, published in Environmental Science & Technology, focuses on nitrate and nitrite, two nitrogen compounds that are closely linked to agriculture and watershed hydrology. Until now, scientists and policymakers have struggled to clearly separate how much nitrogen loss is driven by changes in farming practices versus changes in rainfall, streamflow, and broader climate-related factors. This research directly addresses that gap.

Why Nitrogen Loss Is Such a Big Deal

Nitrogen is an essential nutrient for crops, which is why fertilizers rich in nitrogen are widely used across the Midwest. However, when nitrogen is applied in excess or poorly timed, it can be washed off fields into nearby streams and rivers. Over time, this nitrogen travels downstream, degrading drinking water supplies and contributing to hypoxia, or oxygen depletion, in coastal waters.

The Mississippi River Basin is particularly important in this context. It drains a vast agricultural region, and nitrogen carried by the river is a major driver of the Gulf of Mexico’s annual dead zone. Reducing nitrogen loss from this basin has been a long-standing goal of both state and federal nutrient reduction strategies, but progress has been uneven.

One reason is that nitrogen loss does not respond to a single cause. Farming practices matter, but so do extreme rainfall events, long-term changes in precipitation patterns, and shifts in river flow. Without understanding the relative influence of these factors, it is difficult to know where and how to intervene.

What the Researchers Set Out to Do

The research team, led by Bin Peng from the Department of Crop Sciences at Illinois, set out to separate the human and hydrological drivers of nitrogen export in the Upper Mississippi River Basin. Their goal was not just to measure how much nitrogen was being lost, but to understand why those losses were changing over time and where the dominant drivers were located.

To do this, the team relied on 20 years of water quality data collected by the U.S. Geological Survey. These data came from monitoring sites spread across the Upper Mississippi River Basin and covered the period from 2001 to 2020. Using this information, the researchers calculated annual nitrate and nitrite loads at each site.

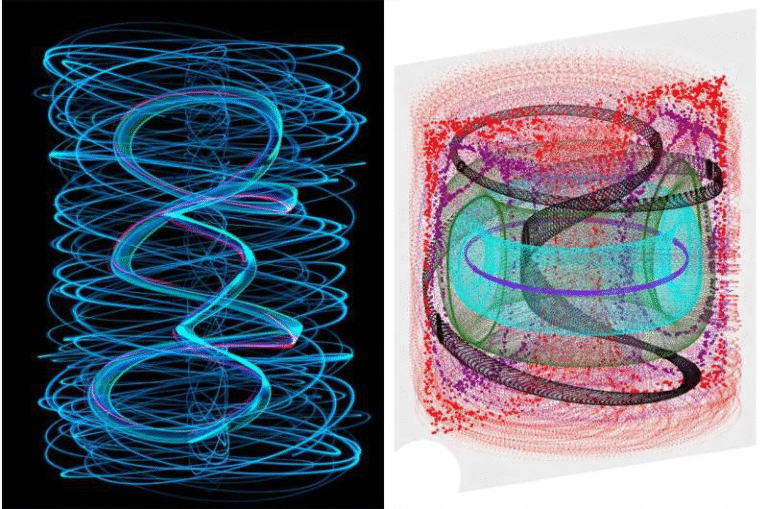

They then calibrated a modified version of the USGS SPARROW model, a widely used tool that links nutrient loads in streams to watershed characteristics. The model accounts for nutrient sources, land-to-water delivery factors, and in-stream processes. By carefully adjusting the model with real observational data, the researchers were able to simulate nitrogen export with a high degree of spatial and temporal detail.

The final step was a factorial scenario analysis, which allowed the team to isolate how much of the observed change in nitrogen loss could be attributed to human activities and how much was driven by hydrological variability.

Two Time Periods, One Clear Trend

The researchers compared two five-year periods: 2001–2005 and 2016–2020. Over these two decades, nitrogen loss across the Upper Mississippi River Basin increased substantially.

On average, nitrogen export rose by nearly 10 kilograms per hectare per year. Importantly, the increase was not dominated by a single cause. Roughly half of the increase was attributed to human activities, such as fertilizer application rates and changes in farm conservation practices. The other half was driven by hydrological changes, including shifts in rainfall patterns and streamflow.

This balanced contribution challenges the idea that nitrogen loss is either mainly a farming problem or mainly a climate and hydrology problem. Instead, it shows that both sets of drivers are deeply intertwined at the regional scale.

Hotspots and Regional Differences Within the Basin

While the basin-wide averages tell an important story, the most useful insights emerged when the researchers examined the data at the sub-watershed level. Here, clear spatial patterns appeared.

In the northwestern part of the Upper Mississippi River Basin, nitrogen loss was strongly influenced by both anthropogenic drivers and hydrological variability. This region showed high contributions from fertilizer and manure inputs, combined with increased precipitation and runoff. In other words, farming practices and changing water dynamics were reinforcing each other.

In contrast, the southeastern part of the basin showed a different pattern. There, hydrological change played a larger role than human activity. Even where fertilizer inputs were not increasing dramatically, changes in rainfall and streamflow still led to higher nitrogen export.

These regional differences are critical because they suggest that a one-size-fits-all approach to nutrient management is unlikely to work.

Implications for Policy and Conservation

One of the most practical outcomes of this study is its potential to inform more targeted nutrient reduction strategies. If policymakers know whether nitrogen loss in a given sub-watershed is driven primarily by human inputs or by hydrological variability, they can design interventions that are more likely to succeed.

In the northwestern Upper Mississippi River Basin, for example, reducing fertilizer and manure inputs could be paired with practices that limit runoff during heavy rainfall, such as improved drainage management or buffer strips. In the southeastern basin, where hydrology is the dominant driver, strategies may need to focus more on managing water flow and adapting to climate variability.

The researchers emphasize that this driver-specific approach could improve outcomes for existing state and federal nutrient loss reduction programs, which often struggle to achieve measurable improvements.

Expanding the Research to the Entire Mississippi Basin

The work does not stop with the Upper Mississippi River Basin. The research team is already expanding their analysis to cover the entire Mississippi River Basin. This broader effort aims to support a science-based, data-driven conservation prioritization framework that can be used by farmers, watershed managers, and policymakers alike.

By identifying where nitrogen reductions will have the greatest impact, the framework could help balance environmental protection with agricultural productivity. The long-term goal is to reduce nutrient loss in ways that benefit both farmers’ bottom lines and downstream ecosystems.

A Broader Look at Hydrology and Nutrient Pollution

This study also highlights a growing reality in environmental science: climate-driven hydrological changes are increasingly shaping water quality outcomes. More intense rainfall events can overwhelm conservation practices that were designed for past conditions, carrying nutrients into rivers even when best management practices are in place.

As a result, nutrient management is no longer just about what happens on the field. It is also about how landscapes interact with changing precipitation patterns, river networks, and in-stream processes. Separating these influences, as this study does, is a key step toward realistic and resilient solutions.

Why This Research Stands Out

What makes this study particularly notable is its ability to quantitatively distinguish between human and hydrological drivers over long time periods and across a large, complex watershed. Previous research often acknowledged both factors but lacked the tools to clearly separate their effects.

By combining long-term monitoring data with an enhanced modeling approach, the researchers have provided a clearer picture of how nitrogen loss evolves over time and space. This clarity is exactly what is needed to move from broad goals to actionable, location-specific strategies.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.5c06476