Sunlight and Seafloor Sediments Reveal a 3,700-Year Climate History of Antarctica

Along the frozen coastline of Antarctica, some of the most valuable clues about Earth’s past climate are hiding in plain sight—not in towering ice sheets or deep ice cores, but in fast ice and the quiet layers of sediment beneath the seafloor. A new international study has shown that these coastal ice remnants preserve a remarkably detailed record of Antarctic climate stretching back 3,700 years, and, surprisingly, this record appears to be closely linked to natural cycles of solar activity.

The research was led by scientists from the CNR Institute of Polar Sciences in Italy, with key contributions from the University of Bonn, and has been published in Nature Communications. By combining marine sediment analysis, biological indicators, and climate modeling, the team has uncovered a long-term pattern in Antarctic coastal ice behavior that goes far beyond what modern satellite data can show.

What Exactly Is Fast Ice and Why Does It Matter?

Ice in the Antarctic does not behave in just one way. Some sea ice floats freely and drifts with winds and currents. When this floating ice is pushed together, it forms pack ice. Fast ice, however, is different. It is firmly attached to the coastline or shallow seabed, unable to move freely.

This distinction is important. Fast ice plays a major role in coastal ecosystems, influences biogeochemical cycles, and provides essential habitat for many Antarctic species, including penguins. In certain regions, it even acts as a natural runway for aircraft, making it strategically important for polar research operations.

Despite its importance, fast ice has been difficult to study over long timescales. Direct observations from satellites only go back a few decades, which is not nearly enough to understand its long-term natural variability.

Looking Beyond Satellites Using Sediment Cores

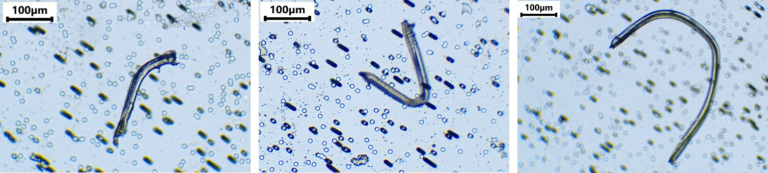

To overcome this limitation, the research team turned to sediment drill cores collected from Edisto Inlet, located along the northern coast of Victoria Land in the Ross Sea. These sediments are special because they contain thin, clearly defined horizontal layers, known as laminae.

Each layer tells a story.

- Dark layers indicate periods when fast ice began breaking up in early summer. These layers are rich in diatoms that live in or near sea ice.

- Light layers signal longer ice-free conditions, with open water dominating the coastal environment. These layers are characterized by the presence of the diatom Corethron pennatum, a species that thrives in open water rather than ice-covered seas.

By analyzing the alternating dark and light layers, the scientists reconstructed a continuous, high-resolution record of fast-ice variability spanning nearly four millennia.

A New Technique With High Precision

The team developed an automated image analysis method to count and analyze the sediment layers with exceptional accuracy. This approach allowed them to identify not just annual changes, but long-term patterns in when fast ice formed, persisted, and broke apart.

The results showed that fast ice does not follow a simple yearly rhythm. Instead, its stability fluctuates in complex cycles over decades and centuries. This finding alone represents a major step forward in understanding Antarctic coastal dynamics.

The Surprising Role of Solar Cycles

One of the most striking discoveries of the study is that fast-ice breakup appears to follow regular cycles of about 90 years and 240 years. These time intervals match well-known patterns in solar activity, specifically the Gleissberg cycle and the Suess–de Vries cycle.

These solar cycles reflect long-term fluctuations in the energy output of the Sun. While the changes in solar radiation are relatively small, the study shows they can trigger a cascade of atmospheric and oceanic effects in Antarctica.

Here’s how the process works:

- Variations in solar activity influence zonal wind patterns over the Southern Ocean.

- These altered winds affect the extent and timing of pack ice retreat along the Antarctic coast.

- When pack ice retreats earlier than usual, fast ice loses its protective buffer.

- Exposed fast ice becomes vulnerable to winds, waves, and warmer ocean water, leading to earlier breakup.

Satellite observations confirm this relationship, showing that fast ice is more likely to break up when nearby pack ice retreats early.

Climate Models Support the Findings

To test their conclusions, the researchers used climate model simulations that exaggerated solar influences. While these simulations do not represent real-world conditions exactly, they clearly demonstrate the underlying mechanism.

The models show that increased solar radiation leads to:

- Warming of the sea surface

- Reduction of insulating sea ice

- Greater heat exchange between the ocean and atmosphere

All of these factors contribute to destabilizing fast ice along the coast.

Why This Matters for Climate Science Today

Understanding natural climate variability is essential for accurately assessing human-induced climate change. Fast ice has long been considered one of the missing pieces in Antarctica’s climate puzzle, and this study fills a major gap.

By establishing a long-term baseline of natural fast-ice behavior, scientists can better distinguish between:

- Changes driven by natural solar and atmospheric cycles

- Changes caused by modern global warming

This distinction is especially important in Antarctica, where small shifts in temperature and ice dynamics can have global consequences, including impacts on sea level and ocean circulation.

Broader Applications Across Antarctica

The implications of this research go beyond one location. Laminated sediments similar to those studied in Edisto Inlet are found in many parts of Antarctica. This means the same technique could be applied to other coastal regions, potentially creating a continent-wide picture of fast-ice dynamics over thousands of years.

Such records would be invaluable for improving climate models and understanding how Antarctica responds to both natural and human-driven forces.

Additional Context: Solar Cycles and Earth’s Climate

Solar cycles have long been studied for their influence on Earth’s climate. While they are not responsible for recent rapid warming trends, they do play a role in long-term natural variability. The Gleissberg and Suess–de Vries cycles, in particular, have been identified in climate records from tree rings, ice cores, and now marine sediments.

This study adds strong evidence that even in one of the most remote regions on Earth, the Sun’s subtle rhythms leave a measurable imprint.

A Step Forward in Antarctic Climate Research

By combining geology, biology, satellite data, and climate modeling, this research offers a practical and scalable method for extending Antarctic ice records far beyond the limits of modern instruments. It also reinforces the idea that Antarctica’s climate system is deeply interconnected with global atmospheric and solar processes.

As scientists continue to refine these methods, fast ice may become one of the most valuable indicators for understanding how Earth’s coldest continent has changed—and how it may change in the future.

Research paper:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-67781-7