The Paris Agreement Is Working — But Economic Growth Is Canceling Out the Gains

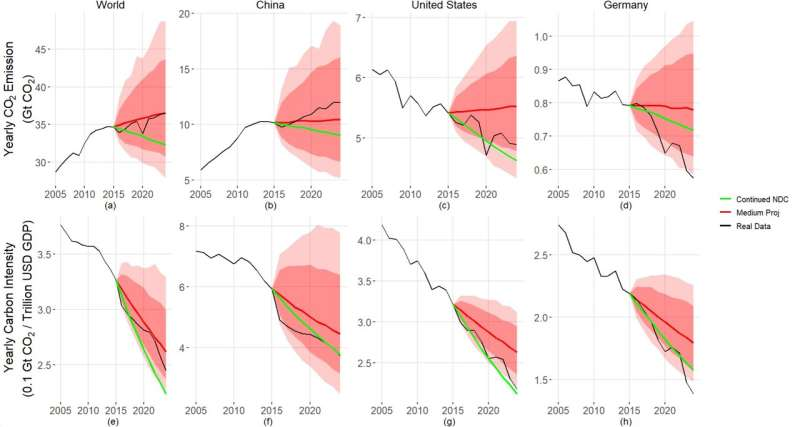

A new decade-long study led by researchers from the University of Washington has found that while the Paris Agreement has indeed pushed the world toward cleaner energy and lower carbon intensity, those achievements are still being undermined by rapid economic growth. In simple terms — countries are producing fewer emissions per dollar earned, but they’re also earning and producing so much more that total emissions keep climbing.

The study, conducted by Jitong Jiang, Skylar Shi, and Adrian Raftery, was published in Communications Earth & Environment in October 2025. It dives deep into global data from the past decade to see how much progress has really been made since the landmark 2015 Paris Agreement came into effect. The conclusion is cautiously hopeful: the Agreement is working, just not fast enough to offset the sheer momentum of global economic expansion.

What the Paris Agreement Set Out to Do

Back in 2015, nearly 200 countries agreed to limit global warming to well below 2°C by the end of this century, ideally aiming for 1.5°C. Each nation submitted a Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) — essentially a 15-year climate pledge to cut emissions and move toward renewable energy.

The Paris Agreement wasn’t just about cutting carbon; it was about creating a framework where every country measures, reports, and updates its progress transparently. The ultimate goal? To “bend the curve” — flattening the rise of greenhouse gas emissions before it’s too late.

Fast-forward a decade, and the new study provides one of the most comprehensive statistical evaluations of how that framework has performed so far.

What the New Study Found

The researchers used a Bayesian statistical model that links population, GDP, and carbon intensity (which measures carbon dioxide emissions per unit of economic output). This allows them to project both past and future emission trends with a probability-based approach — not just a single prediction, but a range of likely outcomes.

Here’s what they found:

- Carbon intensity is dropping faster than before. Since 2015, the world’s carbon intensity has been falling by 3.1% per year, compared to just 1.1% annually before the Paris Agreement.

- But total CO₂ emissions are still rising because the global economy has grown even faster — roughly 41% between 2015 and 2024, or about 3.9% each year. That economic expansion wiped out much of the benefit from cleaner technologies.

- The chance of keeping global warming below 2°C by 2100 has improved slightly — from 5% in 2015 to 17% now. The risk of catastrophic warming above 3°C has dropped from 26% to 9%. That’s genuine progress, but not enough to call it a win.

In short: we’re moving in the right direction, but too slowly.

How the Biggest Economies Are Shaping the Outcome

The study highlights how major economies — particularly China, the United States, and Germany — play an outsized role in the world’s emissions profile.

China, for instance, accounts for nearly one-third of total global CO₂ emissions. The good news: its carbon intensity fell by around 36–37% between 2015 and 2024, meeting and even exceeding its target. The bad news: its emissions still rose about 18% because its GDP exploded during the same period.

The United States also made real progress, cutting its carbon intensity by roughly 32% (around 4.2% per year) since 2015. However, total emissions only fell by about 10%, far short of the reductions needed to stay within the Paris temperature limits.

Meanwhile, Germany, the largest economy in the European Union, continues to outperform both China and the U.S. in terms of carbon efficiency. The study shows China’s carbon intensity is about three times higher than Germany’s, and the U.S. is 50% higher.

This gap underscores how technological efficiency, policy commitment, and industrial structure all matter enormously when it comes to carbon outcomes.

The U.S. Political Roller Coaster

The researchers also modeled what would happen if the U.S. were to stop contributing to emission cuts altogether. The result: global temperatures would rise an additional 0.1°C, and the probability of staying below 2°C would drop from 34% to 27%.

That simulation is a reminder of how much U.S. policy matters globally. When Donald Trump withdrew the country from the Paris Agreement during his presidency, it briefly cast doubt on the entire framework. The Biden administration rejoined and set a goal to cut emissions by 60% from peak levels by 2035, but maintaining that momentum will require consistent leadership and funding.

Why Carbon Intensity Matters

It’s easy to get lost in the jargon, but carbon intensity is one of the clearest indicators of climate progress. It measures how much CO₂ is emitted for every unit of GDP produced. A decline in carbon intensity means we’re getting more efficient — producing goods and services while using less fossil fuel.

Since reducing global economic growth is politically unpopular (and realistically unlikely), improving carbon intensity is the main lever policymakers can pull to curb emissions without stifling prosperity. As Adrian Raftery explains, population growth and GDP expansion are hard to control, but carbon efficiency is within reach of policy and technology.

The global shift toward renewables, cleaner manufacturing, and electric mobility has helped push carbon intensity downward — a clear success of post-Paris policies. Yet those gains are simply not fast enough to offset how quickly the world’s economy and population are growing.

What This Means for the Planet’s Future

The latest data shows the world is on track for roughly 2.4°C of warming by 2100 — down from earlier projections of 2.6°C, but still above the Paris targets. To keep warming under 2°C, the authors estimate that countries would need to make their emissions-reduction efforts about 80% more ambitious than they currently are.

That might sound drastic, but there’s a silver lining: the study also confirms that global cooperation can make a difference. The probability-based models clearly show how the Paris framework has bent the emissions curve downward, even if modestly. Without the Agreement, projections suggest we’d already be heading for 3°C or more of warming this century.

So yes — the Paris Agreement works, but not at the level required to save us from more extreme climate disruption.

Where the World Needs to Go Next

To stay on track, the researchers emphasize three main priorities:

- Accelerate decarbonization – Carbon intensity must keep dropping, ideally by 5–7% per year, not just 3%. That means faster deployment of renewables, clean hydrogen, carbon capture, and electrification.

- Decouple growth from emissions – Economic progress shouldn’t depend on burning carbon. This means shifting investment from fossil-fuel industries to clean infrastructure, sustainable transport, and energy-efficient technologies.

- Strengthen global commitments – The next round of NDCs, due later this decade, will need to be far more ambitious. Incremental progress isn’t enough — countries must aim for structural changes across their entire economies.

Large emitters, especially China, the U.S., India, and Russia, will have the greatest influence on the planet’s fate. Even small improvements in their carbon intensity can outweigh the combined efforts of dozens of smaller countries.

A Quick Refresher: How the Paris Agreement Works

For readers less familiar with the framework, here’s a quick rundown:

- Adopted: December 2015 at COP21 in Paris.

- Entered into force: November 2016.

- Main goal: Limit global temperature rise to well below 2°C, preferably 1.5°C, compared to pre-industrial levels.

- Mechanism: Each country submits an NDC every five years, outlining emission targets and policy measures.

- Accountability: Nations are required to report progress transparently through standardized global frameworks.

- Flexibility: It allows countries to tailor targets to their national circumstances, encouraging broad participation.

The Paris Agreement replaced the top-down approach of the Kyoto Protocol with a bottom-up model — giving countries ownership of their own goals. This design helped make the Agreement nearly universal, but also means that ambition levels vary widely. That’s both its strength and its weakness.

Understanding the Bigger Picture

Climate change isn’t just about CO₂ levels; it’s about balancing energy systems, economic growth, and human welfare. The Paris Agreement operates within that reality. The new study essentially reveals that we’ve made progress on efficiency but failed to rein in the sheer scale of human activity driving emissions.

The takeaway is simple: the system is working, but it needs more fuel — metaphorically speaking — to accelerate. The researchers’ data-driven model gives policymakers a clearer picture of where the bottlenecks are, and which countries need to do more.

On the bright side, the probability of catastrophic climate outcomes has declined since 2015. That’s real progress. Renewable energy is cheaper than ever, electric vehicles are surging, and carbon markets are expanding. The foundations are solid — but the pace needs to pick up.

Why This Study Matters

Unlike political promises or one-off emission reports, this research provides quantitative, probability-based evidence of global climate performance. It shows that global cooperation does move the needle — but it also underscores the urgency for deeper, faster change.

In short:

- The Paris Agreement is not failing. It’s just not strong enough to overcome the scale of global economic growth.

- Carbon intensity is improving, but not at a pace sufficient to reduce total emissions.

- GDP growth and population increases are outpacing our gains in efficiency.

- Stronger policy, cleaner technology, and global coordination remain our best tools to close the gap.

So while the world is finally bending the emissions curve, it’s still not bending it far enough. The next decade will determine whether that curve flattens — or whether the planet keeps heating beyond our control.