The Vast Majority of US Rivers Still Lack Meaningful Protection From Human Activities, New Research Shows

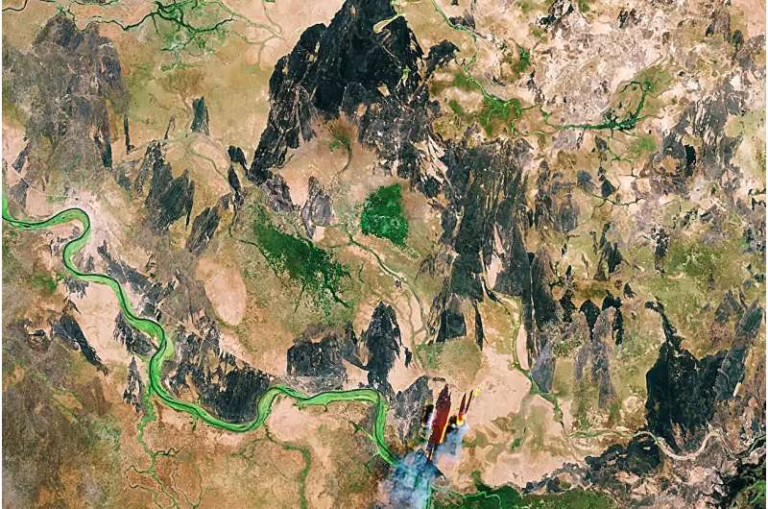

The United States is home to an enormous and diverse network of rivers, with more than 4 million miles of flowing waterways stretching across mountains, plains, forests, farms, and cities. These rivers provide drinking water, food, energy, transportation routes, wildlife habitat, and recreational opportunities for millions of people. Yet despite their importance, a new and comprehensive scientific assessment reveals a troubling reality: most U.S. rivers remain largely unprotected from human impacts.

According to newly published research co-led by scientists at the University of Washington, existing laws and conservation measures cover less than one-fifth of the country’s total river length at a level considered sufficient to maintain healthy river ecosystems. Even more striking, nearly two-thirds of U.S. rivers have no meaningful protection at all.

This study represents the first nationwide effort to systematically evaluate how well America’s rivers are safeguarded and where major gaps remain.

A First-of-Its-Kind National Review of River Protection

For decades, conservation efforts in the U.S. have focused heavily on land-based protections, such as National Parks, Wilderness Areas, National Forests, and Wildlife Refuges. While these protected lands often include rivers within their boundaries, the rivers themselves are rarely the primary focus of protection.

To better understand the actual state of river conservation, researchers created a River Protection Index, a new tool designed to assess how different policies and management practices affect river health. Rather than simply counting how many miles of rivers fall within protected land, the index evaluates river segments based on five key ecological attributes:

- Water quantity

- Water quality

- Connectivity

- Habitat condition

- Biodiversity

Using this approach, scientists layered local, state, and federal protection mechanisms onto a detailed national river map. The goal was to determine not just where protections exist, but how effective those protections are in supporting long-term river resilience.

The Numbers Paint a Stark Picture

The results are sobering. Across the entire United States:

- Nearly 64% of rivers are completely unprotected

- Just over 19% of total river length nationwide meets the criteria for adequate ecological protection

- In the contiguous U.S., that figure drops to around 11%

Protection levels vary widely by region. Rivers flowing through high-elevation, remote, and publicly owned lands tend to fare better, while waterways in lowland areas, agricultural regions, and densely populated parts of the Midwest and South are far less protected.

Headwater streams, which play a critical role in maintaining water quality downstream, are especially vulnerable. Because rivers originate at their headwaters, damage or pollution upstream can undermine conservation efforts far downstream, no matter how well a particular river segment is managed.

Why Rivers Are So Hard to Protect

Unlike forests or grasslands, rivers are dynamic and interconnected systems. They cross political boundaries, flow through multiple land ownership types, and link distant ecosystems together. This makes them particularly difficult to manage under traditional conservation frameworks.

Many threats to rivers — such as agricultural runoff, urban pollution, water withdrawals, and dams — often originate outside protected areas. As a result, even rivers that flow through conservation lands may remain vulnerable if their upstream watersheds are poorly managed.

The study highlights that focusing only on protecting isolated river segments is not enough. A river’s health is inseparable from the condition of its entire watershed, from its source to its mouth.

River-Specific Protections Are Surprisingly Rare

One of the most revealing findings is how little protection comes from river-specific laws and designations.

- The Clean Water Act, passed in 1972 and often considered the cornerstone of U.S. water protection, applies robust safeguards to only 2.7% of total river length

- Habitat protections tied to endangered species cover just 1.3%

- River-focused designations, such as National Wild and Scenic Rivers, protect only about 2% of U.S. rivers

By contrast, land-based protections account for a much larger share of protected river miles:

- Federal Wilderness Areas encompass roughly 6.3%

- Combined river and floodplain protections extend to about 14.2%

While these land-based measures provide indirect benefits, they often fail to address issues like altered flow regimes, blocked migration routes, or upstream pollution.

Uneven Protection Across the Country

Geography plays a major role in determining which rivers are protected and which are not. The study found that protections are heavily skewed toward remote, mountainous, and federally managed landscapes.

Large portions of the Midwest and southern United States, where rivers flow through agricultural land and private property, remain significantly underprotected. These regions often support intensive farming, irrigation, and development, placing additional stress on already vulnerable waterways.

This imbalance raises concerns not only for ecosystems but also for communities that depend on these rivers for drinking water, farming, and local economies.

Why Healthy Rivers Matter More Than Ever

Freshwater ecosystems are experiencing faster biodiversity loss than any other ecosystem type on Earth. Fish populations, aquatic insects, and riparian wildlife are declining at alarming rates, largely due to habitat degradation and water quality issues.

Healthy rivers also provide major economic and social benefits. They supply clean drinking water, support agriculture and hydropower, enable transportation, and offer spaces for recreation and cultural connection. When rivers degrade, the costs often fall on communities, who must invest in expensive water treatment or face increased flood risks.

The researchers emphasize that improving river protection does not mean cutting off access. On the contrary, well-managed rivers tend to support more recreation, stronger local economies, and more resilient ecosystems.

The Case for Watershed-Level Conservation

One of the study’s key recommendations is to expand conservation beyond individual river segments and focus more on protecting entire watersheds. When upstream areas are well managed, downstream communities benefit from cleaner water that often requires less treatment before reaching household taps.

Investing in watershed protection can be both environmentally and economically smart, reducing long-term infrastructure costs while safeguarding biodiversity.

A Clear Roadmap for Future Action

By mapping existing protections and identifying gaps, this research provides a clear foundation for future river conservation strategies. It also aligns with growing international efforts, such as global biodiversity targets that aim to protect 30% of land and water by 2030.

The study makes it clear that while the U.S. has made progress in conserving land, its rivers have been left behind. Closing this gap will require coordinated action across agencies, states, landowners, and communities — and a shift toward treating rivers as ecosystems in their own right, not just features of the landscape.

Research Reference

National assessment of river protection in the United States, Nature Sustainability

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41893-025-01693-8