The World’s First Full Earth System Simulation at 1 km Resolution Is a Big Deal for Climate Science

Climate science has just crossed an important threshold. For the first time ever, researchers have successfully run a full Earth system simulation at an extremely fine 1–1.25 km global resolution, a level of detail that was previously considered out of reach. This breakthrough has now been formally recognized with the 2025 ACM Gordon Bell Prize for Climate Modeling, one of the most prestigious awards in high-performance computing.

This achievement is not just about faster computers or better code. It fundamentally changes what scientists can study, predict, and understand about climate change and its real-world impacts.

What “Full Earth System Simulation” Actually Means

To understand why this matters, it helps to unpack the phrase full Earth system simulation.

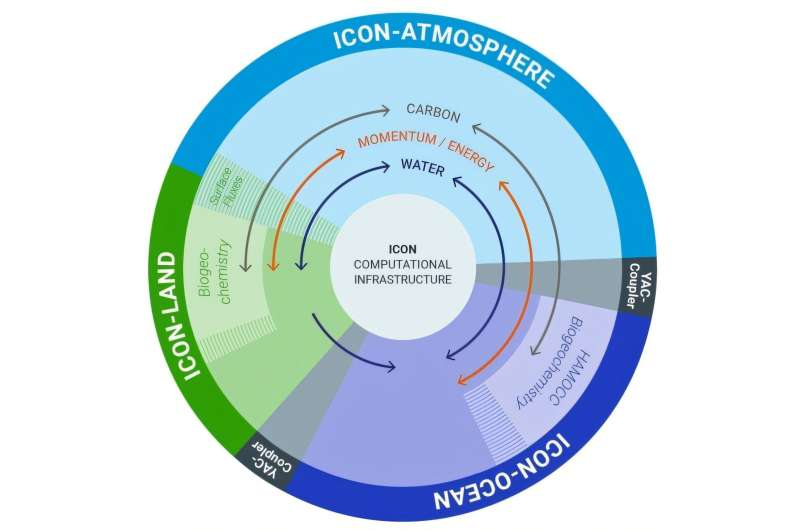

Most climate models focus on only part of the planet’s behavior. Some prioritize the atmosphere, others the oceans, and some treat land processes in simplified ways. These models are powerful, but they often rely on approximations when it comes to how different systems interact.

A full Earth system model brings together all major components at once:

- Atmosphere

- Oceans

- Land surfaces

- Energy flows

- Water cycles

- Carbon cycles

In this new simulation, all of these components are fully coupled, meaning they exchange information continuously rather than being calculated separately. This allows scientists to observe how changes in one part of the system ripple through the rest of the planet.

What makes this effort unprecedented is the global scale combined with near-kilometer resolution. At around 1.25 km grid spacing, the model captures fine-scale processes that older global models simply could not resolve.

Why Resolution Matters So Much

Resolution determines how detailed a simulation can be. Traditional global climate models often operate at resolutions of 50 to 100 km, which smooth out many local processes. At that scale, individual storms, ocean eddies, and land-surface variations are heavily averaged.

At 1 km resolution, the situation changes dramatically:

- Cloud systems can be represented far more realistically

- Ocean-atmosphere interactions become sharper

- Land features, such as mountains, coastlines, and vegetation differences, are captured with much higher fidelity

This level of detail allows scientists to study climate behavior on local and regional scales, even though the simulation itself is global. That’s especially important because climate impacts—heat waves, floods, droughts, and extreme storms—are experienced locally, not as global averages.

The Team and the Gordon Bell Climate Prize

The work was carried out by a 26-member international research team drawn from leading institutions in climate science and high-performance computing. Their effort earned them the ACM Gordon Bell Prize for Climate Modeling, an award specifically created to recognize computational breakthroughs aimed at addressing the global climate crisis.

The prize highlights innovations in parallel computing, algorithm design, and efficient use of modern hardware, all of which were critical to making this simulation possible.

Supercomputers Behind the Simulation

Running a global Earth system model at 1 km resolution requires staggering computational power. The team relied on two of the world’s most advanced supercomputing systems:

- Alps, using 8,192 GPUs

- JUPITER, using 4,096 GPUs

Both systems are based on NVIDIA GH200 superchips, which combine CPUs and GPUs into a tightly integrated, high-bandwidth architecture. This type of heterogeneous computing is especially well suited to climate modeling, where different parts of the simulation benefit from different types of processors.

Altogether, the simulation involved an unprecedented number of degrees of freedom, pushing current hardware and software to their limits.

Key Computational Innovations

Raw computing power alone was not enough. The team introduced several important technical strategies to make the simulation feasible.

One major advance was the use of functional parallelism, where different components of the Earth system—such as atmosphere, ocean, and land—are mapped efficiently onto specialized hardware resources. This allowed each component to run where it performs best.

Another important choice was separating scientific model implementation from hardware-specific optimization. Core components were written in Fortran, a language long favored in climate science, while optimization layers handled performance tuning for the target architectures. This approach made the code both portable and scalable, a critical requirement for future systems.

The result was a simulation that achieved remarkable time compression, meaning it could simulate many days of Earth system behavior in a much shorter amount of real-world computing time.

What This Means for Climate Research

This simulation opens doors that were previously closed.

With full coupling between energy, water, and carbon cycles, scientists can explore how future warming scenarios influence ecosystems, weather extremes, and long-term climate patterns at resolutions that matter to people and environments.

Some of the potential benefits include:

- Better understanding of extreme weather formation

- More accurate assessments of regional climate risks

- Improved insight into carbon feedback mechanisms

- Stronger links between global climate trends and local impacts

Importantly, the researchers emphasize that this kind of detailed global information simply did not exist before at this scale.

Why Earth System Modeling Is So Hard

Earth system modeling has always been one of the most demanding challenges in science. The planet operates through countless interacting physical, chemical, and biological processes, all evolving over vastly different time scales.

Water cycles through evaporation, precipitation, and runoff. Energy moves between the Sun, atmosphere, oceans, and land. Carbon flows through ecosystems, oceans, and human activity. Capturing all of this simultaneously, without oversimplification, requires not only advanced physics but also massive computational resources.

This is why previous models often had to compromise—either by lowering resolution or by simplifying interactions. The new simulation shows that those compromises are no longer strictly necessary.

Looking Ahead

While this simulation is a major milestone, it is not the final destination. Instead, it serves as a proof of concept for what next-generation Earth system modeling can achieve.

As supercomputers continue to grow more powerful and energy-efficient, similar simulations could become more common, longer-running, and more accessible to the global climate research community. The techniques developed here will likely influence climate models for years to come.

In short, this work demonstrates that global, high-resolution, fully coupled Earth system simulations are now possible—and that changes the landscape of climate science in a very real way.

Research Paper Reference:

Computing the Full Earth System at 1 km Resolution (2025), Proceedings of the International Conference for High Performance Computing, Networking, Storage and Analysis

https://doi.org/10.1145/3712285.3771789