Tracing Mountain Water and the Hidden Systems That Keep Headwater Streams Flowing

Mountain headwater streams may look small on the surface, but they are some of the most important water sources in regions like the Rocky Mountains. These upper-mountain streams make up more than 70% of the entire river network, feeding larger waterways, supporting ecosystems, and supplying water to communities downstream. Yet scientists still know surprisingly little about how these streams continue flowing long after the snowmelt rush fades. A new study led by researchers from the University of Connecticut and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory takes a deep dive into that question, uncovering how snowmelt timing, vegetation, and subsurface geology work together to shape streamflow throughout the year.

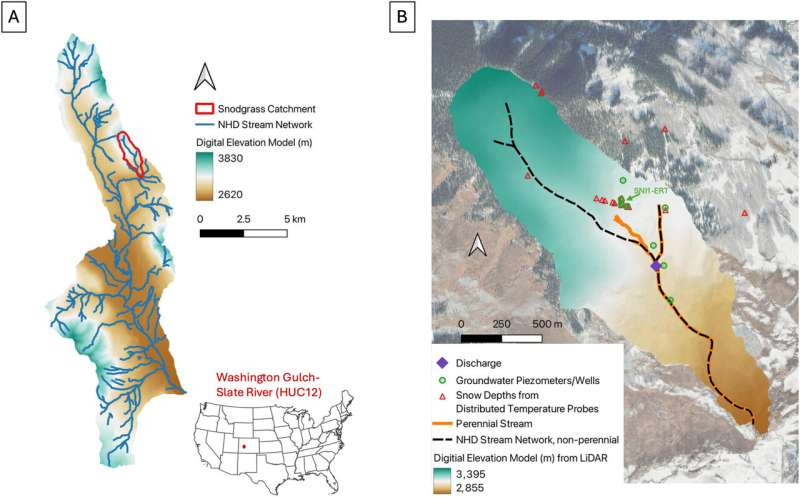

This research was conducted in a mountainous watershed near Crested Butte, Colorado, specifically focusing on the Snodgrass catchment within the Washington Gulch–Slate River watershed. The goal was straightforward: understand where late-season streamflow comes from once snowmelt ends, and determine which environmental and geological factors control the hidden water reservoirs feeding these streams.

Snowmelt Timing and the Role of Vegetation

In mountain regions of the Western United States, snowmelt is the dominant source of water feeding streams during spring and early summer. But once that snowmelt pulse passes, summertime rainfall doesn’t contribute much to streamflow because most of it evaporates or is absorbed by vegetation. So what keeps streams flowing? Scientists know the water must come from subsurface storage, but the details of how that water is stored and released are not well understood.

The research team analyzed a large dataset collected across the catchment, including snow depth, groundwater levels, and streamflow measurements. One notable finding was that vegetation strongly influences snowmelt timing. Areas covered by evergreen forests experienced snowmelt one to two weeks later than areas dominated by shrubs, grasses, or deciduous trees, even when located at the same elevation. The evergreen canopy shades the snowpack and insulates it, slowing its melt rate.

This difference matters because evergreen areas act like a natural regulator. The delayed melting and gradual release of water from snowpack under evergreens prevents sudden spikes in streamflow and helps sustain moderate levels over a longer period. This means forest composition can directly affect how mountain streams behave. If evergreen forests are cleared, it could significantly disrupt the region’s hydrological balance by accelerating snowmelt and reducing the duration of streamflow.

The Surprise of a Second Groundwater Peak

The groundwater data revealed an unexpected pattern: two distinct peaks in groundwater levels each year. The first one makes sense—it occurs during peak snowmelt, when melting snow recharges underground water reserves. But a second peak later in the season caught researchers’ attention.

To understand this, the scientists used a powerful modeling framework that let them simulate different subsurface scenarios by adjusting factors such as porosity, permeability, and geological layering. They discovered that the second peak likely occurs because of a geological transition in the catchment’s subsurface.

The upper hillslope consists primarily of granodiorite, a type of fractured bedrock that allows water to infiltrate and store underground. Beneath it lies Mancos shale, a softer, less permeable layer. This creates a natural “bathtub” effect: snowmelt fills the upper granodiorite zone until it builds up enough pressure and spills over into lower layers or begins moving laterally. When this overflow happens, groundwater levels rise again, causing the second peak.

This mechanism shows how important subsurface structure is to seasonal water movement. Without understanding the geology underneath these slopes, scientists would miss key processes controlling streamflow long after the snowmelt season.

How Permeability Controls Late-Season Streamflow

One of the study’s major takeaways is the outsized role of permeability, which determines how easily water moves through underground materials. If subsurface permeability is high, stored snowmelt water can gradually flow toward streams, providing steady discharge during late summer and early fall. But when permeability is low, water becomes trapped and cannot reach the stream efficiently.

This means late-season streamflow can vary dramatically depending on local geology. Two mountain slopes that look identical on the surface might behave very differently if one has a subsurface layer that restricts flow. For downstream communities and ecosystems relying on consistent water supply, this matters a great deal—especially in regions already facing drought pressure.

Why Understanding Hidden Water Sources Matters

Predicting water availability is growing more difficult as climate change reshapes snowpack levels, snowmelt timing, and vegetation patterns. If snow melts earlier or forests shift due to fire, disease, or warming temperatures, headwater streams could experience major changes in flow timing and volume. This, in turn, affects everything from aquatic species to agricultural water supply.

With the insights from this study, hydrologists can now build more accurate models that reflect not just surface conditions but also the complex realities underground. The team’s integration of detailed field data and flexible modeling allowed them to pinpoint which factors have the strongest effect on water movement—something that was previously unclear because most headwater sites lack continuous monitoring.

The researchers acknowledge that not every mountain catchment will have such extensive datasets, so they are working on using proxy data and AI-driven techniques to make similar modeling possible in less monitored regions. Improved predictive tools will help communities prepare for water-related challenges and understand how climate-driven changes could affect freshwater resources.

Extra Background: Why Headwater Streams Are So Important

Since this topic revolves around hydrology and mountain water systems, it’s helpful to understand why these small streams matter so much. Here are some key facts that add context:

They Feed Most of the River Network

Headwater streams are the starting points of larger rivers. When they dry up or shrink, the effects ripple downstream. Because they make up the majority of river miles, any changes in their behavior can influence whole watersheds.

They Support Biodiversity

Cold, clean water from mountain snowmelt supports species like trout, amphibians, and aquatic insects. Temperature changes caused by reduced late-season flow can stress or eliminate these species.

They Recharge Groundwater

Snowmelt that infiltrates into the ground replenishes aquifers, which many communities depend on. Understanding subsurface water storage is essential for long-term water planning.

They Are Sensitive to Climate Change

Warmer temperatures mean earlier snowmelt, reduced snowpack, and potentially less groundwater recharge. Research like this helps scientists predict how mountain hydrology will shift in the coming decades.

They Are Hard to Study

Mountain terrain makes long-term monitoring expensive and logistically challenging. This is why the new modeling advances from the research team are valuable—they allow scientists to extract insights even with limited datasets.

Improving Predictions for the Future

The combination of vegetation controls, snowmelt timing, subsurface geology, and permeability paints a more complete picture of what sustains mountain streams. By understanding how these factors interact, scientists can reduce uncertainty in water forecasts and create better models for other regions lacking comparable data.

The research team emphasizes that with so many headwater streams across the United States, it’s impossible to monitor each one intensively. Tools that blend data with flexible modeling and incorporate AI will be essential for making meaningful predictions. As climate change continues to influence hydrologic systems, being able to anticipate shifts in water availability becomes more urgent.

Research Paper:

The Role of Snowmelt and Subsurface Heterogeneity in Headwater Hydrology of a Mountainous Catchment in Colorado: A Model-Data Integration Approach

https://doi.org/10.1029/2025wr040651