UN Scientists Say the World Has Entered an Era of Global Water Bankruptcy Affecting Billions

The world has officially moved into what United Nations scientists are calling an “era of global water bankruptcy”, a new and troubling phase in humanity’s relationship with water. According to a major new report from the United Nations University (UNU), many regions across the planet are no longer just facing temporary water shortages or isolated crises. Instead, they are operating in a post-crisis reality where water systems have been pushed beyond their natural limits, with damage that is often irreversible or extremely costly to undo.

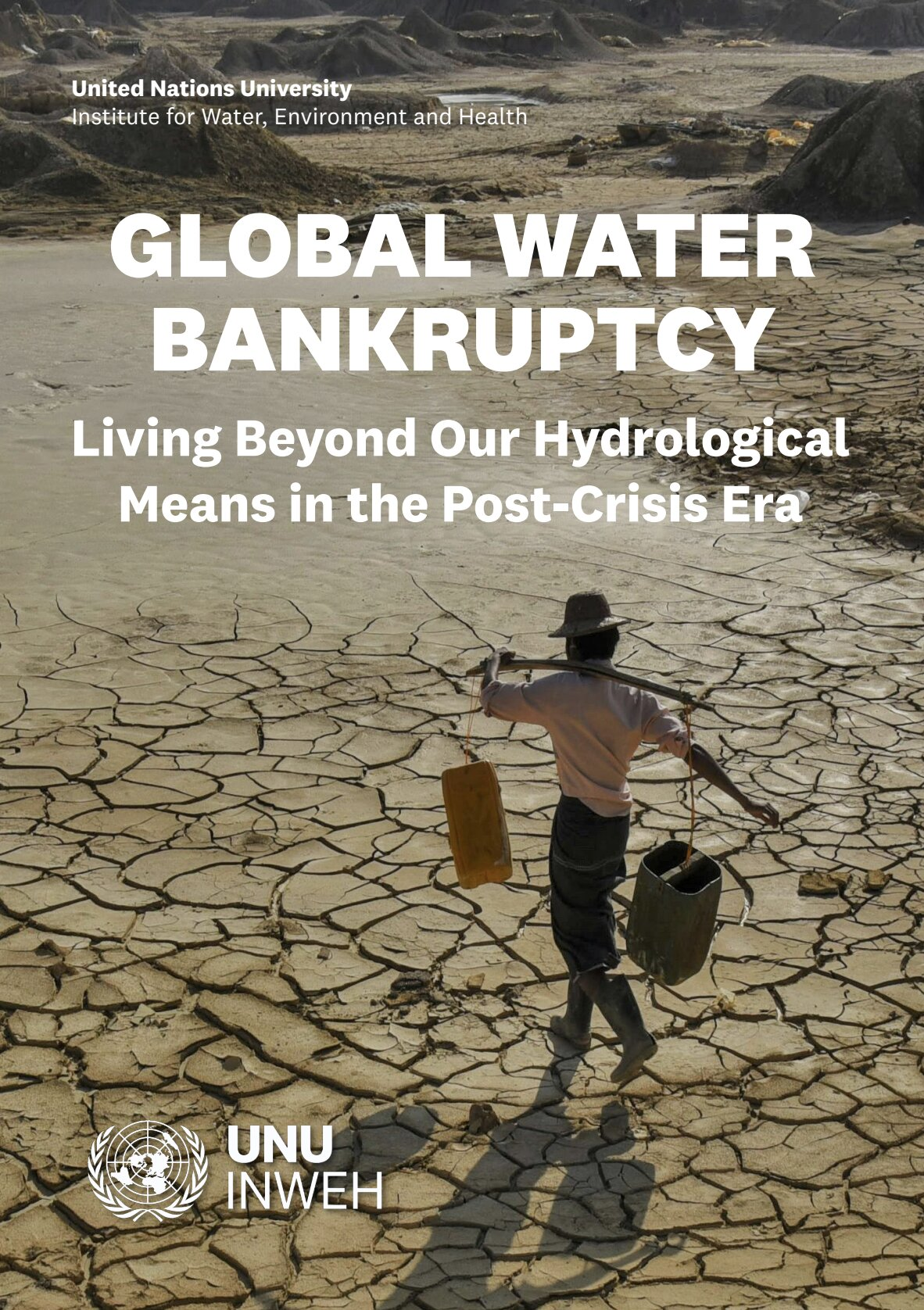

The report, titled Global Water Bankruptcy: Living Beyond Our Hydrological Means in the Post-Crisis Era, was produced by the United Nations University’s Institute for Water, Environment and Health (UNU-INWEH), often described as the UN’s think tank on water. It argues that commonly used terms like water stress and water crisis are no longer adequate to describe what is happening in many parts of the world today.

What “Global Water Bankruptcy” Actually Means

In simple terms, water bankruptcy occurs when societies consistently withdraw more water than nature can safely replenish, and in doing so, permanently degrade or destroy the natural systems that store and supply water. The report formally defines water bankruptcy as:

- Persistent over-withdrawal from surface water and groundwater compared to renewable inflows and safe depletion thresholds

- The resulting irreversible or prohibitively expensive loss of water-related natural capital, including aquifers, glaciers, wetlands, rivers, soils, and ecosystems

This concept borrows language from finance. Just as financial bankruptcy happens when spending exceeds income and savings are exhausted, water bankruptcy occurs when societies use up not only their annual renewable water “income” from rainfall, rivers, and snowpack, but also drain their long-term “savings” stored in aquifers, glaciers, wetlands, and lakes.

Once those savings are gone, recovery becomes either impossible or far beyond realistic economic and political capacity.

Why Older Terms No Longer Fit

The report makes a clear distinction between older water-related terms and this new diagnosis:

- Water stress refers to high pressure on water resources that is still largely reversible

- Water crisis describes acute shocks, such as droughts or floods, that can potentially be overcome

- Water bankruptcy, by contrast, reflects a chronic, structural condition where systems have crossed critical thresholds

A region can experience flooding one year and still be water bankrupt if its long-term withdrawals consistently exceed replenishment. In this framework, water bankruptcy is not about whether a place looks wet or dry, but about balance, accounting, and sustainability over time.

The Human Drivers Behind the Crisis

According to the report, the overwhelming majority of water bankruptcy drivers are human-caused. These include chronic groundwater depletion, water overallocation, land and soil degradation, deforestation, pollution, and poorly planned infrastructure. All of these pressures are being intensified by global heating, which disrupts rainfall patterns, accelerates glacier melt, and increases evaporation.

The visible consequences are already widespread: compacted aquifers, sinking cities, collapsed wetlands, vanished lakes, degraded soils, and severe biodiversity loss. Sinkholes caused by unsustainable groundwater extraction are highlighted as a classic symptom of water bankruptcy.

A Stark Global Picture

Using global datasets and recent scientific evidence, the report paints a sobering statistical picture of how deeply the world is in the red:

- 50% of large lakes worldwide have lost water since the early 1990s, affecting 25% of humanity that depends on them

- 50% of global domestic water now comes from groundwater

- 40%+ of irrigation water is drawn from aquifers that are steadily being drained

- 70% of major aquifers show long-term declines

- 410 million hectares of natural wetlands have disappeared over the past five decades, nearly the size of the European Union

- 30%+ of global glacier mass has been lost since 1970, with many mountain regions expected to lose functional glaciers within decades

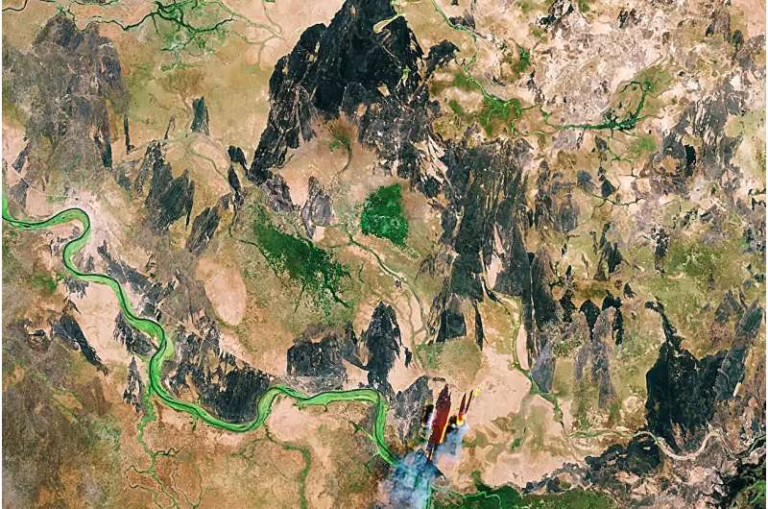

- Dozens of major rivers now fail to reach the sea for part of the year

- Many river basins and aquifers have been overdrawing water for more than 50 years

The human consequences are equally severe:

- 75% of humanity lives in countries classified as water-insecure or critically water-insecure

- 4 billion people face severe water scarcity for at least one month every year

- 2 billion people live on sinking ground caused by groundwater depletion

- Some cities are experiencing land subsidence of up to 25 centimeters per year

- 170 million hectares of irrigated cropland are under high or very high water stress

- US$5.1 trillion is the estimated annual value of lost wetland ecosystem services

- 3 billion people live in areas where total water storage is declining or unstable, including regions that produce more than 50% of the world’s food

- 1.8 billion people lived under drought conditions in 2022–2023 alone

- The current annual global cost of drought is estimated at US$307 billion

- 2.2 billion people lack safely managed drinking water, while 3.5 billion lack safely managed sanitation

Global Hotspots of Water Bankruptcy

While not every basin or country is water bankrupt, the report highlights several regions where multiple risks intersect:

- In the Middle East and North Africa, extreme water stress combines with climate vulnerability, low agricultural productivity, energy-intensive desalination, and frequent sand and dust storms

- In South Asia, groundwater-dependent agriculture and rapid urbanization have led to chronic water table declines and widespread land subsidence

- In the American Southwest, the Colorado River system has become a symbol of water that was historically over-promised and is now severely overdrawn

Because water systems are interconnected through trade, migration, climate feedbacks, and geopolitics, failures in one region can trigger cascading effects elsewhere. Food systems, in particular, are deeply linked to water availability.

Why This Is a Global Risk, Not a Local One

Agriculture accounts for the vast majority of freshwater use worldwide. When water scarcity undermines farming in one region, the impacts ripple through global food prices, political stability, and food security. This makes water bankruptcy a shared global risk rather than a collection of isolated local problems.

The report argues that managing this reality requires bankruptcy management, not traditional crisis management. Some losses cannot be reversed, but further damage can still be prevented.

Rethinking the Global Water Agenda

The report warns that the current global water agenda, which focuses largely on drinking water, sanitation, and incremental efficiency improvements, is no longer fit for purpose in many regions. It calls for a reset that includes:

- Formal recognition of water bankruptcy

- Treating water as both a constraint and an opportunity for climate, biodiversity, and land goals

- Elevating water in climate, biodiversity, desertification, development finance, and peacebuilding negotiations

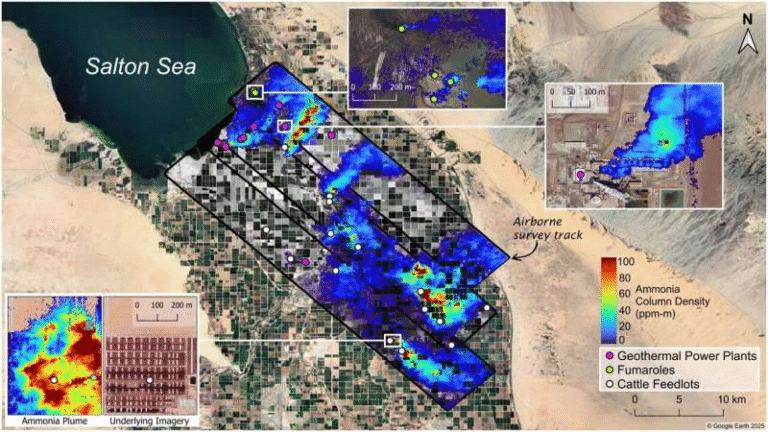

- Embedding water-bankruptcy monitoring using Earth observation, AI, and integrated modeling

- Using water as a catalyst for cooperation among UN Member States

In practical terms, governments are urged to prevent further irreversible damage, rebalance water rights to reflect degraded carrying capacity, support just transitions for affected communities, transform water-intensive sectors like agriculture and industry, and build institutions capable of continuous adaptation.

A Justice and Security Issue

The report emphasizes that water bankruptcy is not just a hydrological problem. It is also a justice issue, with disproportionate impacts on smallholder farmers, Indigenous Peoples, low-income urban residents, women, and youth. At the same time, the benefits of overuse have often accrued to more powerful actors.

Water bankruptcy is increasingly linked to fragility, displacement, and conflict, making fair and transparent management essential for peace and stability.

A Difficult but Necessary Reality Check

Declaring global water bankruptcy is not framed as a message of hopelessness. Instead, it is presented as a call for honesty and realism. Just as in financial systems, acknowledging bankruptcy is often the first step toward rebuilding on more sustainable terms.

The upcoming 2026 and 2028 UN Water Conferences, the end of the Water Action Decade in 2028, and the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals deadline are highlighted as critical opportunities to act.

The longer meaningful action is delayed, the deeper the global water deficit will grow.

Research paper: https://doi.org/10.53328/INR26KAM001