Utah’s Other Great Salt Lake Lies Underground and It’s Ancient, Deep, and Fresh

Beneath the cracked, salty surface of Utah’s Great Salt Lake lies something few scientists fully understood until recently: a vast body of pressurized freshwater, hidden underground, ancient in origin, and surprisingly extensive. New research led by geoscientists from the University of Utah reveals that this unseen reservoir has been quietly accumulating for thousands of years, challenging long-held assumptions about how water moves through and beneath one of the most iconic lakes in North America.

At first glance, the Great Salt Lake is defined by its salinity, its shrinking shoreline, and the environmental concerns tied to drought and water diversions. But below the lake’s exposed playa, researchers have identified a freshwater aquifer that exists beneath a thick, salty barrier. This discovery adds an entirely new layer to scientists’ understanding of the lake’s hydrology and opens up important questions about groundwater, ancient climate history, and future environmental management.

A Vast Freshwater Body Beneath a Salty Surface

The newly studied groundwater system lies beneath sediments that fill the basin west of the Wasatch Mountains. Over time, snowmelt from these mountains has percolated downward, slowly filling pore spaces in the sediments. What makes this groundwater remarkable is that it sits below a salty layer roughly 30 feet thick, often referred to by researchers as a saltwater lens.

This lens acts like a cap, trapping the freshwater beneath it under pressure. In certain locations, that pressure becomes strong enough to push freshwater upward through weak points in the salty layer, allowing it to breach the surface.

These breaches are not subtle. They appear as strange circular mounds or islands, often choked with reeds, scattered across parts of the exposed lakebed, especially in Farmington Bay. For years, these features puzzled scientists and observers alike. Now, they are understood to be visible windows into a much larger underground system.

The Mystery of the Round Spots

These circular features, sometimes called “phragmites oases” or “mystery islands,” form where pressurized freshwater finds a pathway upward. Researchers discovered that the size of each round spot correlates with how fresh the groundwater is at its center. Larger mounds tend to have fresher water, while salinity increases toward the edges.

Fieldwork involved drilling wells of varying depths into these mounds and installing piezometers, instruments that measure water pressure and flow. Data collected over two years showed that these mounds act like vertical pipes or channels, allowing freshwater to move through the saltwater lens and reach the playa surface.

Interestingly, sediment within these round spots is often coarser than surrounding areas, which may help explain why water can move upward more easily there. Why these features are circular, why the sediment differs, and whether deeper geological structures play a role are still open questions that scientists are actively investigating.

An Aquifer With Ice Age Roots

One of the most striking findings is the age of the groundwater. Isotope analysis suggests that some of the water trapped beneath the playa dates back thousands of years, possibly even to the Ice Age. This places its origin during or shortly after the era of Lake Bonneville, the massive freshwater lake that once covered much of northwestern Utah and began shrinking into today’s Great Salt Lake around 8,000 years ago.

The ancient age of this water tells researchers something important: this groundwater is not rapidly cycling into the Great Salt Lake. Instead, it has been stored underground for millennia, largely isolated from modern surface processes. Complementary studies indicate that while large volumes of groundwater flow off the mountain front, much of that water reaches the lake indirectly by seeping into rivers rather than traveling straight through the playa.

A Collaborative, High-Tech Investigation

This research effort is led by hydrologists Bill Johnson and Kip Solomon, working alongside the U.S. Geological Survey Water Science Center and the Utah Geological Survey. Graduate student Ebenezer Adomako-Mensah played a central role, leading the piezometer study that formed the basis of the first published paper in the Journal of Hydrology.

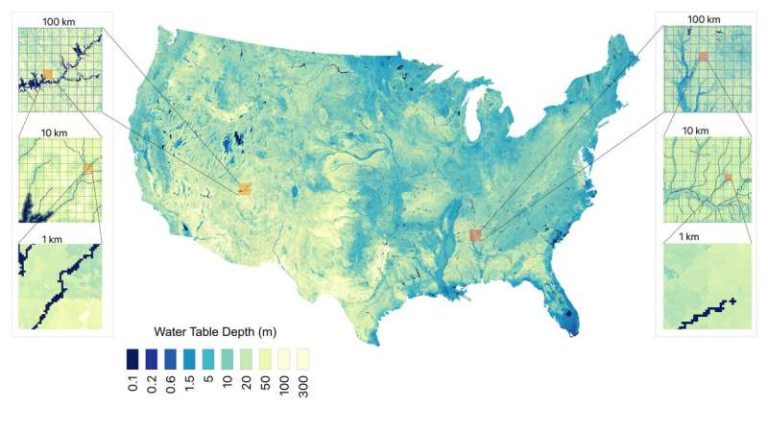

The project uses a wide range of tools to map and understand this hidden water system. These include isotope analysis to determine water age and recharge elevation, electrical resistivity tomography to image subsurface structures, and airborne electromagnetic surveys to help build a three-dimensional picture of the deep playa sediments. Together, these methods are revealing just how extensive the pressurized freshwater system may be, possibly extending beneath much of the eastern playa and even under parts of the lake itself.

Why This Freshwater Matters

Despite its size, researchers are careful to stress that this aquifer is not a solution to the Great Salt Lake’s water crisis. Its slow recharge rate and ancient nature make it unsuitable as a large-scale water supply for refilling the lake.

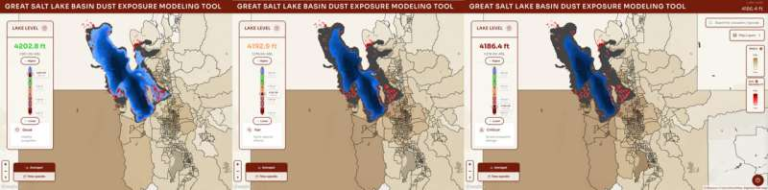

However, it may still play a valuable role. One proposed use is dust mitigation. As lake levels drop, exposed playa sediments can become a major source of dust storms that affect nearby communities along the Wasatch Front. Carefully tapping small amounts of this pressurized freshwater could help re-wet certain high-risk dust areas without disrupting the overall system, though scientists emphasize that this idea requires much more study.

Understanding this aquifer also reshapes how scientists think about groundwater flow in terminal lakes, offering insights that could apply to similar saline basins around the world.

Additional Context: Groundwater Beneath Saline Lakes

Hidden freshwater beneath salty lakes is not entirely unique, but it is rarely documented at this scale. In many terminal lake systems, salinity is assumed to dominate from surface to depth. Discoveries like this one highlight how layered and complex groundwater systems can be, especially in regions shaped by ancient climate shifts.

Such aquifers can preserve long-term records of past precipitation, temperature, and mountain hydrology, making them valuable not just for water management but also for paleoclimate research. In this sense, the freshwater beneath the Great Salt Lake is as much a scientific archive as it is a hydrological feature.

A Discovery That Raises More Questions

Rather than closing the book on Great Salt Lake hydrology, this research opens many new chapters. Scientists are now asking whether the ancient vertical flow beneath the playa connects with younger lateral groundwater coming off the mountains, and how these systems interact over time. Each answer seems to generate new questions, ensuring that this hidden freshwater lake will keep researchers busy for years to come.

Research paper:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhydrol.2025.134813