When Companies Go Green the Air Quality Benefits Can Be Very Different Than You Might Expect

Organizations around the world are trying to reduce their environmental footprint. Common strategies include buying renewable electricity, cutting back on business flights, or offsetting carbon emissions to meet net-zero goals. On paper, many of these actions look equivalent because they reduce the same amount of carbon dioxide. But new research from MIT shows that when it comes to air quality and human health, these choices are far from equal.

A team of researchers from MIT, Harvard University, and Imperial College London set out to answer a deceptively simple question: if two climate actions reduce the same amount of CO₂, do they deliver the same benefits for air quality? Their answer is a clear no. In fact, some “green” actions can cause three times more air quality damage than others, even when the climate impact is identical.

The study, published in Environmental Research Letters, focuses on two major sources of organizational emissions: electricity purchases and air travel. While both contribute to climate change, their effects on air pollution, public health, and geography differ in striking ways.

Understanding the difference between climate and air quality impacts

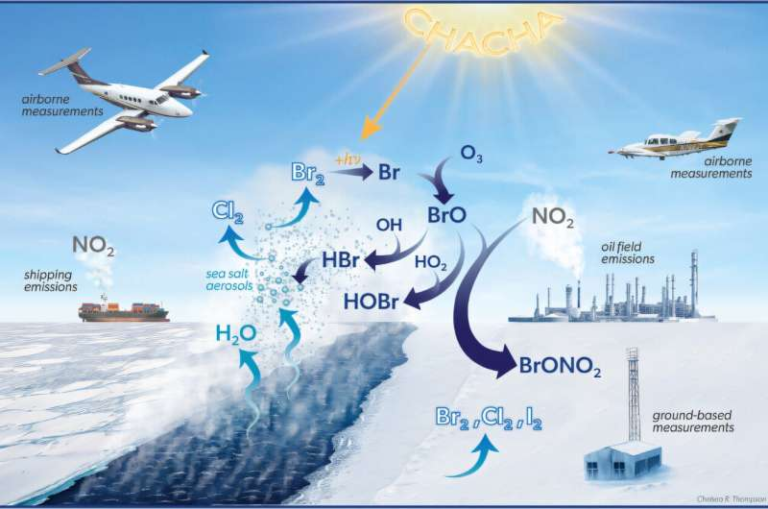

Carbon dioxide behaves differently from most air pollutants. Once released, CO₂ mixes evenly throughout the atmosphere, meaning its climate impact is global, regardless of where it is emitted. Air quality, however, is driven by co-pollutants such as nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), sulfur dioxide (SO₂), and fine particulate matter known as PM2.5.

These pollutants do not spread evenly. Their effects depend heavily on where emissions occur, local weather, atmospheric chemistry, and population density. Exposure to PM2.5 and ground-level ozone is linked to cardiovascular disease, respiratory illness, and premature death. This makes air quality impacts far more localized and complex than climate impacts.

The researchers wanted to move beyond national or regional averages and look closely at how individual organizations’ decisions affect air pollution and health outcomes.

How the researchers approached the problem

The study analyzed real-world data from three organizations in the greater Boston area: two universities and one corporation. The researchers examined how different actions that removed the same amount of CO₂ from the atmosphere affected air quality.

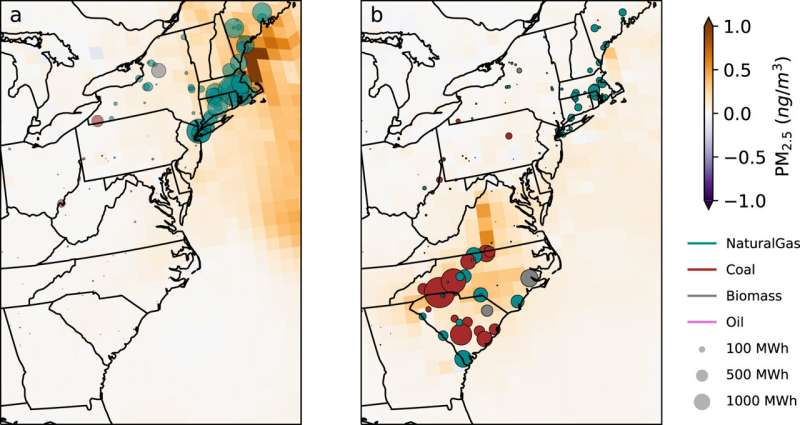

To do this, they built a systems-level modeling pipeline that connected several complex components. These included electricity generation data from individual power plants, emissions inventories, aviation flight routes, atmospheric chemistry transport models, and statistical relationships between pollution exposure and mortality.

The model traced emissions from their source, simulated how pollutants formed and moved through the atmosphere, and estimated changes in ground-level PM2.5 and ozone. Finally, the researchers translated these pollution changes into monetized health damages, allowing direct comparison with climate damages from CO₂.

This approach was technically challenging. The researchers ran multiple sensitivity analyses to ensure the modeling pipeline behaved consistently and realistically across different scenarios.

Air travel causes much larger air quality damage than electricity use

One of the most important findings is that air travel has a dramatically higher air quality impact than electricity purchases for the same CO₂ reduction.

Using established economic methods, the researchers estimated that the climate damage of CO₂ emissions is about $170 per ton (in 2015 dollars). On top of that, they calculated additional air quality damages.

For electricity purchases, air quality damages amounted to approximately $88 per ton of CO₂. For air travel, however, the number jumped to about $265 per ton of CO₂. This means that air travel produces roughly three times more air quality damage than electricity use when normalized by carbon emissions.

Why aviation is so damaging to air quality

The outsized impact of air travel comes down to altitude and atmospheric chemistry. Most aircraft emissions occur at high altitudes, where pollutants behave very differently than they do near the ground. At these heights, chemical reactions can amplify the formation of fine particulate matter.

These emissions are also carried long distances by global wind patterns, meaning their impacts are often felt thousands of miles away from where flights originate. Unlike power plant emissions, which mostly affect nearby regions, aviation pollution has a global footprint.

The study found that countries such as India and China experience particularly severe air quality impacts from aviation emissions. This is because high-altitude pollution interacts with already elevated ground-level emissions, increasing the formation of PM2.5 and smog in densely populated areas.

Short-haul flights matter more than many people think

The researchers also took a closer look at short-haul flights, which are often overlooked in sustainability strategies. Surprisingly, short regional flights were found to have a larger local air quality impact than longer domestic flights.

This means organizations aiming to improve air quality in their immediate surroundings could see meaningful benefits by reducing short-distance flights or replacing them with other forms of transportation. From a public health perspective, cutting regional air travel may deliver more immediate benefits than focusing only on long-haul flights.

Electricity emissions depend heavily on location

Electricity purchases may appear cleaner than air travel, but the study shows that location still matters a great deal. Power plant emissions tied to electricity use affect air quality differently depending on where those plants are located and how many people live nearby.

In the study, emissions linked to one university fell over a densely populated region, while emissions linked to the corporation affected areas with fewer residents. Even though the climate impacts were identical, the university’s electricity use resulted in 16% more estimated premature deaths due to higher population exposure.

This highlights an important point: not all electricity is equal from an air quality standpoint, even if the carbon footprint looks the same.

Why net-zero strategies are not interchangeable

One of the clearest messages from the study is that which ton of CO₂ you eliminate first really matters. Two organizations may reach net zero using different strategies, yet the consequences for human health and air quality can vary widely.

Climate accounting often treats all CO₂ reductions as equal, but this research shows that focusing only on carbon can hide serious trade-offs. A smarter approach considers co-pollutants, geography, and population exposure, allowing organizations to maximize near-term health benefits while still meeting climate goals.

Additional context on air quality and health

Fine particulate matter, or PM2.5, is especially dangerous because it can penetrate deep into the lungs and enter the bloodstream. Long-term exposure has been linked to heart attacks, strokes, asthma, and shortened life expectancy. Ground-level ozone, another major pollutant, worsens respiratory conditions and contributes to smog.

Because air quality impacts are felt quickly, unlike climate change which unfolds over decades, policies that reduce PM2.5 and ozone can deliver immediate public health benefits. This makes air quality an important, and often underappreciated, part of sustainability planning.

What the researchers want to study next

The team plans to expand their analysis to include train travel, particularly as a substitute for short-haul flights. They also want to examine the air quality impacts of other energy-intensive activities, such as data centers, which are growing rapidly in the U.S.

By refining these tools, the researchers hope to give organizations better guidance on how to design climate strategies that also protect human health.

Ultimately, the study sends a clear message: going green is not just about cutting carbon. It is about understanding how, where, and from what source emissions are reduced, and choosing paths that deliver the greatest benefits for people as well as the planet.

Research paper:

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ae21f9