Widespread Sediments Beneath Greenland Could Make Its Ice Sheet More Vulnerable to Warming and Sea-Level Rise

Scientists studying the Greenland Ice Sheet have uncovered new evidence that could significantly change how we understand future sea-level rise. A recent study reveals that soft, widespread sediments lie beneath much of Greenland’s ice, making the ice sheet potentially far more responsive to warming than many existing climate models assume. This finding narrows a long-standing uncertainty about what lies beneath the ice and why Greenland continues to lose ice at an accelerating pace.

Greenland plays an outsized role in global sea-level rise. As the climate warms due to human-driven fossil fuel emissions, ice sheets in polar regions are melting faster, sending vast amounts of freshwater into the oceans. While scientists have become increasingly good at tracking surface melting, one major unknown has remained: the nature of the ground beneath the ice sheet, also known as the basal environment. This new research helps fill that gap.

What the Study Found Beneath the Ice

The study, published in October 2025 in the journal Geology, reports that soft sediment is far more widespread beneath the Greenland Ice Sheet than previously thought. These sediments are not confined to coastal areas or fast-moving outlet glaciers. Instead, they extend deep into the interior of Greenland, even under regions where the ice is extremely thick.

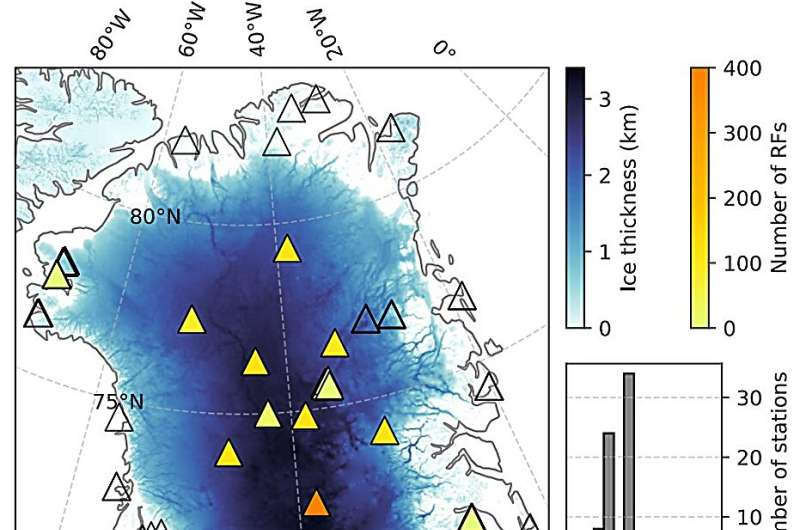

The research team relied on a long-term seismic survey, analyzing data from 373 broadband and short-period seismic stations deployed across Greenland. Many of these instruments were part of established monitoring efforts, including the Greenland Ice Sheet Monitoring Network and the XF seismic network operated by researchers at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.

Rather than drilling through kilometers of ice, the scientists used passive seismic methods. This technique examines how seismic waves from distant earthquakes travel through the Earth. As these waves pass through different materials—ice, sediment, or solid bedrock—their speed and behavior change. By carefully studying these changes, researchers can infer what lies beneath the ice without physically accessing it.

Why Sediments Matter for Ice Flow

The distinction between hard bedrock and soft, wet sediment beneath an ice sheet is critical. Ice moves toward the ocean in two main ways: by slowly deforming internally and by sliding along its base. When ice rests on solid bedrock, friction slows this sliding motion. However, when the base consists of water-saturated, loose sediment, the ice can slide much more easily.

This study shows that large parts of Greenland’s ice sheet sit atop exactly this kind of weak, deformable sediment. As surface temperatures rise, meltwater can drain down through cracks in the ice and reach the base. When that water interacts with sediment, it reduces friction even further, allowing glaciers to speed up and discharge ice into the ocean more rapidly.

This process has direct implications for sea-level rise. Faster ice flow means greater ice loss, even if surface melting rates remain the same.

How Scientists Mapped the Basal Conditions

To build the most complete picture yet of Greenland’s subsurface, the research team analyzed seismic signals generated by teleseismic earthquakes, meaning earthquakes that occurred thousands of kilometers away. These events, typically with magnitudes greater than 6, produce seismic waves that travel through Earth’s interior and are recorded by Greenland’s seismic stations.

Using a method known as receiver function analysis, scientists measured how seismic waves changed as they crossed boundaries between different materials. Ice, sediment, and bedrock each leave distinct seismic signatures. By combining data from across the ice sheet, the researchers produced a continent-scale view of Greenland’s basal composition.

They also integrated ice thickness information from BedMachine version 5, one of the most detailed datasets available for Greenland’s ice geometry. This allowed them to assess uncertainties in ice thickness beneath each seismic station and better interpret the subsurface signals.

A More Vulnerable Ice Sheet Than Expected

One of the most striking findings is that sediments occur even beneath thick interior ice, not just near the margins. This challenges older assumptions that Greenland’s interior rests mostly on hard crystalline bedrock. Instead, the presence of sediment suggests that some regions may respond more quickly and dramatically to future warming.

The study also found that sediment distribution varies over relatively small distances. This means that current models, which often rely on coarse assumptions about basal conditions, may miss important local variations that influence ice flow.

According to the researchers, if warming continues and more meltwater reaches the ice-bed interface, these sediments could weaken further. That would allow ice to accelerate even more, increasing Greenland’s contribution to global sea-level rise beyond current projections.

Why This Matters for Sea-Level Predictions

Greenland is already one of the largest contributors to rising sea levels. Even small changes in how quickly its ice moves can have global consequences, affecting coastal flooding, erosion, and saltwater intrusion.

Climate models depend heavily on assumptions about basal conditions. If those assumptions are wrong—if the bed is softer and more lubricated than expected—then future sea-level rise could be underestimated. This study provides critical data that can help refine models and reduce uncertainty, which is essential for planning coastal defenses and adaptation strategies worldwide.

The Role of Subglacial Sediments in Glacial Systems

Beyond Greenland, this research highlights a broader truth about glaciers and ice sheets: what lies beneath them matters enormously. Subglacial sediments are common in many glaciated regions, especially where glaciers have eroded the landscape over millions of years.

These sediments can store water, deform under pressure, and interact dynamically with ice. In some cases, they act almost like a slow-moving fluid beneath the ice, dramatically altering glacier behavior. Understanding these interactions is now seen as one of the key frontiers in glaciology.

What Comes Next for Researchers

While this study represents a major step forward, it also points to the need for denser seismic networks across Greenland. Higher-resolution data would allow scientists to map sediment thickness and properties in greater detail and track how these conditions change over time.

Researchers are also interested in combining seismic data with other methods, such as radar imaging and numerical modeling, to build a more complete picture of Greenland’s evolving ice system.

A Clearer Picture, But Higher Stakes

By revealing widespread soft sediments beneath the Greenland Ice Sheet, this research removes one layer of uncertainty while raising the stakes for climate projections. Greenland may be more sensitive to warming than previously believed, meaning that future sea-level rise could arrive faster and with greater impact.

As scientists continue refining their models, one thing is becoming increasingly clear: understanding the hidden world beneath the ice is just as important as monitoring what happens on its surface.

Research Paper:

https://doi.org/10.1130/G53653.1