Wildfires Can Turn Harmless Soil Minerals Into Toxic Contaminants, New Research Shows

Wildfires are already known for their destructive effects on forests, wildlife, and communities. Now, new scientific research shows they may also trigger a much less visible but potentially long-lasting problem beneath our feet: the transformation of naturally harmless soil minerals into toxic contaminants that can threaten groundwater and human health.

A recent study led by researchers at the University of Oregon reveals that extreme heat from wildfires can chemically alter chromium found in certain soils, converting it from a beneficial micronutrient into a known carcinogen. The findings add an important new layer to our understanding of how fires reshape landscapes long after the flames are gone.

How a Useful Mineral Becomes a Dangerous Pollutant

Chromium is a naturally occurring element found in rocks and soils across the world. In most environments, it exists primarily as chromium-3, a form that plays a role in human metabolism and is generally considered harmless at environmental levels.

However, chromium also has a more dangerous form: chromium-6. This version is widely known due to its association with industrial pollution and has been classified as a Class A carcinogen, linked to lung, sinus, and nasal cancers. What makes chromium-6 especially concerning is its ability to dissolve easily in water, allowing it to move through soils and contaminate groundwater.

The University of Oregon study demonstrates that wildfire-level heat can drive the chemical oxidation of chromium-3 into chromium-6, even in areas untouched by industrial activity.

Simulating Wildfires in the Lab

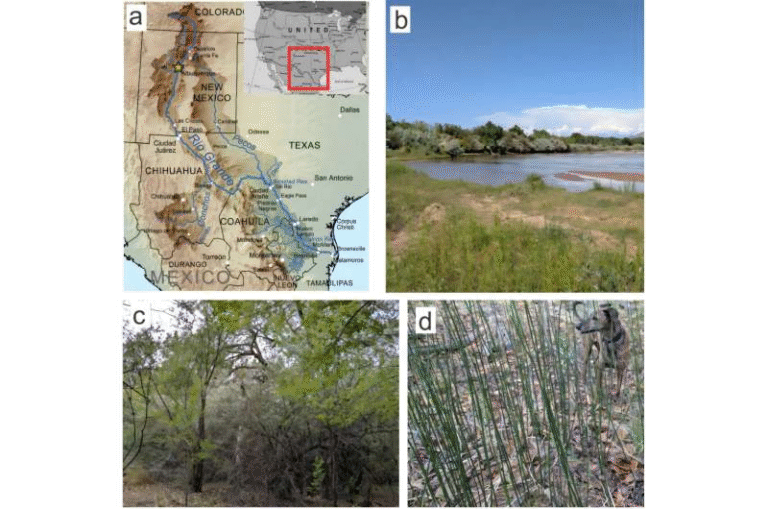

To understand how this transformation happens, researchers collected soil samples from Eight Dollar Mountain, located in southwestern Oregon within the Rogue River–Siskiyou National Forest. This region is rich in serpentinite rocks, which naturally contain high levels of chromium-3 and are increasingly vulnerable to wildfires.

The team gathered soils from multiple elevations along the mountain, including the summit and lower slopes. This was important because soils change significantly with landscape position. Summit soils tend to be more weathered, meaning the rock has broken down over time and released more chromium into the soil.

In the laboratory, researchers exposed these soil samples to temperatures ranging from 400 to 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit for two hours, simulating wildfire conditions. The results were clear: soils heated to between 750 and 1,100 degrees Fahrenheit produced the highest concentrations of chromium-6.

Why Soil Location Matters

One of the most striking findings was that landscape position strongly influenced chromium conversion.

Soils from the summit of Eight Dollar Mountain produced the most chromium-6 when heated to around 750 degrees Fahrenheit. Because summit soils experience greater weathering, they contain more readily available chromium-3, which can be converted into chromium-6 at relatively lower temperatures.

In contrast, soils from lower slopes required higher temperatures, closer to 1,100 degrees Fahrenheit, to generate similar levels of contamination. This shows that wildfire intensity alone does not determine contamination risk; where the soil is located on the landscape is equally important.

Testing the Risk to Groundwater

The researchers didn’t stop at heat experiments. To understand how chromium-6 might move through the environment after a fire, they conducted leaching experiments. Burned soils were packed into columns, and rainwater was pumped through them for a week. This simulated roughly six months of natural rainfall moving through the soil.

The water that drained out was analyzed for chromium-6. In several cases, concentrations were high enough to exceed U.S. Environmental Protection Agency drinking water standards.

Depending on soil type and location, the contamination could persist in groundwater for six months to nearly two and a half years. This suggests that the effects of a wildfire may linger far longer than the visible burn scars.

Prescribed Burns vs. Wildfires

An important distinction emerged in the study. Lower-intensity fires, such as prescribed or cultural burns commonly used in forest management, did not appear to generate significant amounts of chromium-6 under the tested conditions.

While the researchers caution that more study is needed, this finding suggests that controlled burns may carry less risk of triggering heavy-metal contamination compared to high-intensity wildfires.

A Gap in Post-Fire Monitoring

Currently, post-fire assessments conducted by agencies like the U.S. Forest Service focus on erosion risks, slope stability, and immediate public safety concerns. Chromium-6 is not routinely monitored, even in areas with chromium-rich geology.

The study highlights a growing need to expand post-fire environmental testing, particularly in landscapes known to contain metals such as chromium, manganese, nickel, or lead. Fires can mobilize these elements, allowing them to migrate into soils, streams, and aquifers.

Why This Research Matters More Than Ever

The Pacific Northwest and many other regions are experiencing increasing wildfire frequency and severity. Climate change, prolonged droughts, and higher temperatures mean that soils are being exposed to extreme heat more often than in the past.

This research shows that wildfires don’t just remove vegetation or alter ecosystems at the surface. They can fundamentally change soil chemistry, creating contamination risks in places that were previously considered geologically safe.

Understanding Chromium in the Environment

Chromium exists naturally in many rocks, especially serpentinite formations. Under normal conditions, chromium-3 remains relatively immobile in soils. Problems arise when it is oxidized into chromium-6, which is far more mobile and toxic.

Historically, chromium-6 contamination has been associated with industrial waste, metal plating, and chemical manufacturing. The new research underscores that natural processes, intensified by wildfires, can produce similar risks without any industrial pollution involved.

What Comes Next

Scientists involved in the study emphasize that this work represents an early step. Much remains unknown about how widespread wildfire-driven chromium contamination may be, how long it persists across different ecosystems, and whether airborne dust could also pose a health risk after fires.

Future research will likely focus on:

- Other metal contaminants activated by fire

- Long-term monitoring of groundwater in burned areas

- How fire management strategies influence chemical outcomes

As wildfires continue to shape landscapes worldwide, understanding these hidden chemical transformations will be essential for protecting water quality, ecosystems, and public health.

Research Paper Reference:

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.est.5c08315